I was re-watching “Love” last month. It’s a show I don’t consider to be that good but one that holds a personal significance for me, so I come back to it often. One of the main characters, would-be screenwriter Gus, explains at one point what he wants to do in Hollywood. “I really love erotic thrillers,” he says, “but they don’t really make them anymore. Usually because they’re super sexist or racist.”

Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa doesn’t exactly fit the bill of “erotic thriller,” not in the same way classics like Basic Instinct and Body Heat do so perfectly. But it occurs to me that we don’t make these kinds of movies anymore, either: A sadder but wiser version. Let’s call it erotic espionage. And we stopped making them, I’m pretty sure, for the same reasons.

Like many erotic thrillers, Mona Lisa opens with its main character in a compromised position. George, a down-on-his-luck ex-con, is freshly released from a 7-year prison term when the film begins. He’s lonely, he’s lower-class, and he’s looking for something. At first, this something is his teenage daughter, whom he’s been disallowed from seeing by his ex-wife. When he shows up at their door with a bouquet of flowers, he’s turned out unceremoniously. He truly seems to have no one in his life, save his close friend Thomas, a mechanic with a side hustle making plastic, realistic food items, and glow-in-the-dark Virgin Mary statuettes.

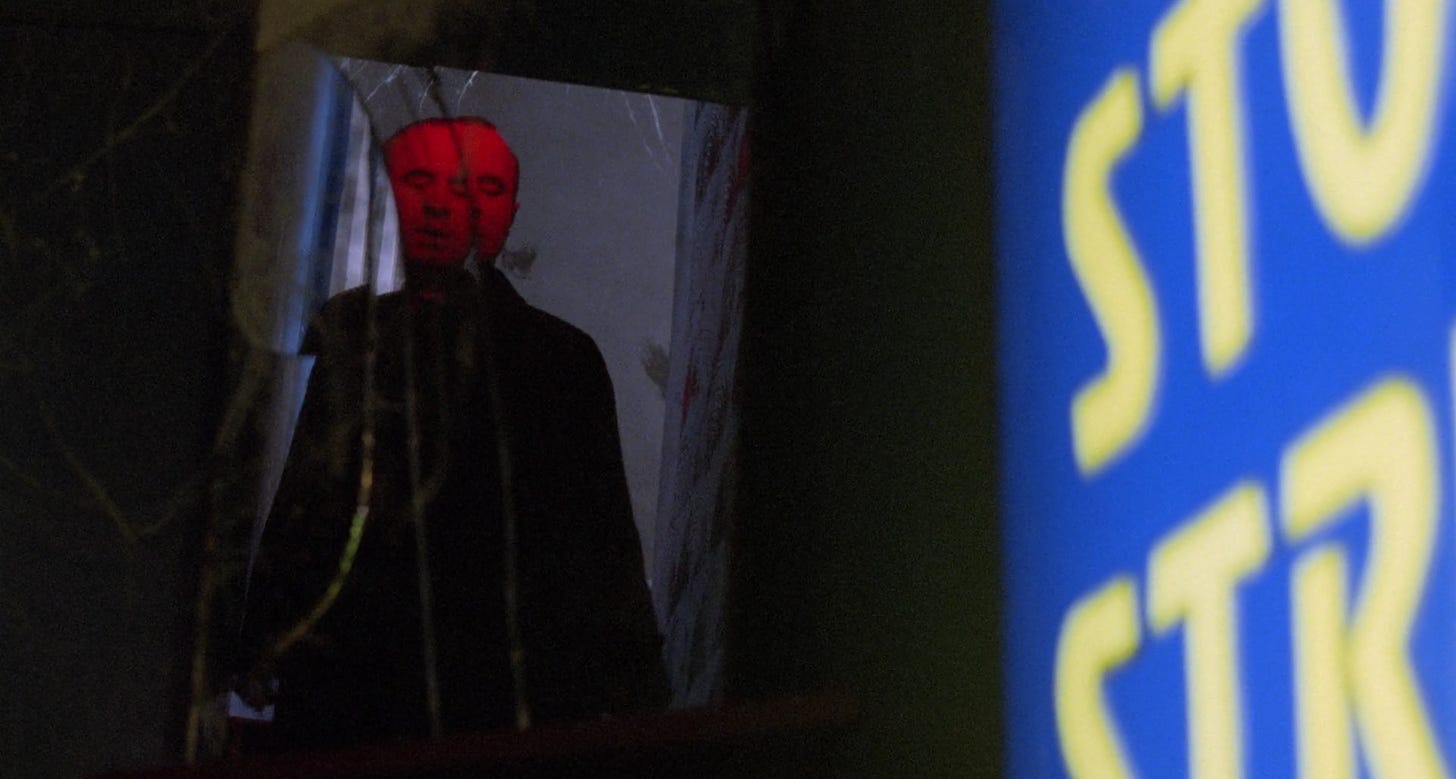

So he goes to his gangster ex-employer (Michael Caine) and asks for a job. He gets one, as a driver to Simone (Cathy Tyson,) who George describes as a “thin, tall Black tart.” Meaning she’s a sex worker. A very high-end sex worker who dresses in men’s fashions and often wears just a huge men’s overcoat over some lingerie and stockings. As Simone’s driver, George starts to become interested in filling in some of the blanks in Simone’s past. She keeps asking him to drive her to King’s Cross, where sex workers wander around trying to make a score for the night. She’s looking for someone. When she finally tells him who, he joins the search: a dark, seedy quest that quickly consumes him as he roams the Red Light district at dusk, surveying every Peep Show and strip club to make sure the girl he’s looking for isn’t there.

George suffers from a lack of boundaries, one might say, between life and workplace. He’s a driver, and that’s all he is, but when he’s driving Simone around, she makes him feel like he’s somehow wrong for the job. “I’m cheap,” he tells her, and he keeps telling her. At first she hates the way he dresses, he’s loud and likes ugly printed shirts and insists on proudly wearing his cheapness on his sleeve. Everywhere he goes to pick her up, he insists on ordering a huge Bloody Mary and just sits there, not tipping, basically asking for them to get kicked out.

Because Simone is Black, it doesn’t matter to the hotel employees how high-class a sex worker she is. They’re always waiting and watching, preparing to pounce. And George’s classlessness doesn’t help. At one point, Simone takes him shopping and shows him how it feels to wear a suit that actually fits. He looks in the mirror and experiences a moment of seeing how clothes can transform a person, and the transformation shocks him. She keeps building him up, and through this reverse-Pygmalion process, she ends up grooming him to be what she wants. And getting him to do the dirty work for her. By the end, he learns that she’s not only a “dyke,” but a pedophile chasing after an underage girl. All this time, George thought Simone was looking out for this girl. As it turns out, she was just as much of a predator as everyone else.

This revelation breaks George’s heart. By the end, he has to watch Simone murder two men who were about to murder her. He realizes just how much he’s been used, and it all dawns on him at once, causing him to break down in sobs. At heart, he just wanted some semblance of a relationship with Simone. He takes her to the seaside at one point, desperate to make them something like a real couple. “Show me the sights!” he keeps yelling at her, before pressing her into a forced kiss. “This is what men and women do,” he explains. All she wants to do is get away. And because it’s the 80s, the film can only frame her struggle to get out from under the oppressive thumb of white pimps and gangsters as a desperate example of two-faced conniving on her part. It’s George the film wants us to feel for, and it’s George who gets out of it alive, largely unscathed.

When Simone calls him a good guy at one point, he asks “how can you tell?” The same way we can: through the simple act of comparing him to everyone else in this movie, who are pretty patently evil. We see George at the end, relaying the whole story for Thomas, who he’s joined at the mechanic shop. He seems happy, and it feels like his part of the story has ended without leaving much of a mark on him at all. We don’t see what happens to Simone, or Cathy, her underaged lover. I guess we’re not supposed to care.

The whole point of erotic thrillers, looking back at the spate of them we had in the 80s and 90s, was to tell a story about sex and vulnerability from the man’s point of view. These films positioned women—proudly sexual, predatory, and usually murderous—as evil forces that just sort of happen to hapless men. These women—exemplified by Linda Fiorentino in The Last Seduction and Kathleen Turner in Body Heat—were supposed to be seen as cautionary tales: See what happens when women get as much access to sex and power as men? They become monsters! But a movie like Mona Lisa is different. Yes, George gets used. Yes, Simone turns out to be more complicated than a mere damsel in distress. But the relationships they each have to power and sex are left unexplored in favor of a kind of false equivalency. Simone and George are both disenfranchised, but their problems aren’t the same. The problems of women and men in this genre are never on the same level, especially when race enters into it.

Neil Jordan has a history of making this kind of mistake. His most famous film, The Crying Game, would come out six years later and follow much the same pattern as Mona Lisa: Underworld guy falls for femme fatale of color who turns out to be something more complicated. In The Crying Game, of course, the violence only hinted at in this film becomes explicit. The famous moment of Stephen Rea, as a reaction to seeing Jaye Davidson’s naked trans body, violently throwing up created a de facto blueprint for all films after, as if to say: “here’s the only logical reaction to this situation.” It’s a problem that all erotic thrillers have, the sexist/racist part of the equation that Gus nods to in “Love.” These were largely films made by men, imagining a kind of male vulnerability that can only exist when women—and trans women or queer folks—can pose a threat, usually of deception. Men can only be vulnerable onscreen if someone else pays for it, often with their lives.

Simone survives, but she’s ultimately left behind by the film, in the same way Jaye Davidson’s Dil gets left behind the minute she stands nude before the camera. Movies like this leave people behind, and that’s probably why we’ve left the genre itself behind. We can’t afford to tell stories about evil nymphomaniacs or murderous dykes anymore. We know the politics are bad, even though the movies can be great.

Ultimately though, the erotic thriller is a genre that we killed for less noble reasons. These are sad movies about sad men. For a time, movies like this gave us a window into male vulnerability that we hadn’t had before. Noir was always full of tough guys with unchanging faces, not sad losers who break down crying in public. But the price we paid for this vulnerability was the agency of the film’s non-male, often non-white characters. That’s always how it is: for a man to be vulnerable, a woman has to be devious. At least, in films like this it’s always the case. And we probably stopped making them not because we got wiser, but because the films themselves stopped selling.

I’d like to think that we did away with the unpleasant conventions of this genre to make way for something better: a more nuanced, less politically fucked version of a noir or erotic thriller. But we haven’t. That would require a kind of interest in and empathy for the characters always relegated to the fringes of such genres, an interest that most people who make movies that make money just don’t seem to have. So maybe we’ll never rehabilitate this genre. Maybe it will remain buried, gathering dust with each passing year. And that’s okay.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox