If someone had told me one of my favorite films from Sundance would be about a thrash metal band in Lebanon, I wouldn’t have believed them. But Rita Baghdadi’s Sirens—executive produced in part by Maya Rudolph and Natasha Lyonne—is one of the rare documentaries that plays like a really good narrative film. It would make a great double bill with Alex and Sylvia Sichel’s All Over Me, a 25-year-old movie about young women in the riot grrrl scene. Like that film, Sirens traces the fraught friendship, musical partnership and falling out between two women: Lilas, a guitarist and default leader of the all-woman thrash metal band Slave to Sirens and the band’s other guitarist and co-leader Shery.

“My parents always told me there was no future here,” says 23-year-old Lilas, who is queer and open about her identity with the filmmakers, but not necessarily with her mother, who she lives with. In spite of the pro-LGBTQ+ street graffiti captured at the film’s beginning, we continually hear talk of measures to outlaw homosexuality, as well as about the censorship of another band from Lebanon, the recently broken up Mashrou’ Leila, whose lead singer is an out gay man known for performing with rainbow flags.

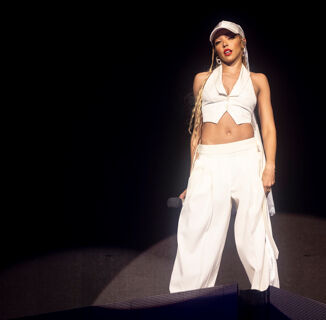

With their bondage-inspired outfits, lead vocals that sound like Linda Blair in The Exorcist and coordinated head banging of Shery and Lilas’s long dark hair, Slave to Sirens aren’t going to be adorning their performances with rainbows of any kind soon. Gigs in their home country are hard to come by. They’re invited to play at the UK’s Glastonbury music festival on a small record label’s “low-budget” stage and manage to attract some fans onto the at-first empty field, but this big break is a palpable letdown.

Shery and Lilas often take to the streets: chants, signs and crowds become as much a backdrop to the film as Lilas’s home environment.

Back home, things are hardly better. Lilas’s mother speaks of being able to withdraw only $100 at a time from the bank (part of Lebanon’s ongoing financial crisis) and the electricity goes out several times during filming, at one point putting an end to a rehearsal. A huge explosion (caught in real time) kills 218 people in one of the busiest parts of Beirut. We assume the blast is an attack, but it’s actually a result of government corruption and neglect. Because of this, Shery and Lilas—who first met at a protest—often take to the streets: chants, signs and crowds become as much a backdrop to the film as Lilas’s home environment.

Lilas is dating women, sometimes across borders. One prospective serious girlfriend visits her at home—Lilas reminds her not to call her “babe” in front of her Mom. Later, the couple have a romantic afternoon at the beach together, but as her girlfriend leaves, Lilas laments that she’ll never be able to move away from Syria.

Shery and Lilas’s conflicts, often but not always about the band (Lilas says, “I thought it was all about music, but it wasn’t all about music,”) have an underlying tension, the reason for which, late in the film, is spelled out and will have queer women in the audience saying, “I knew it!” Although the two do play together again (Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir”!) Lilas begins forging her own path. She cuts her hair: her striking face suddenly androgynous, framed by a bob that won’t whip back and forth to the music in the same way it does with Shery’s in earlier scenes.

Shery is less open to us and to the filmmakers, though we do get a scene in which her father says that at her age, 27, other women have children, though he knows that’s not her priority. He’s already lost that battle, so he suggests that maybe she could play poppier music instead.

Director Baghdadi also serves as the film’s DP and producer, assuring that it looks stunningly beautiful from frame to frame. We see the band lit by magenta and blue stage lights and outdoor shots showing the women walking among wildflowers. Other times, the women are posing for a photographer in the bombed-out ruins of a huge cavernous building.

The tendency in documentaries about people—especially those not in the West—creating art under difficult circumstances is for filmmakers and audiences to ooh-and-aah over the perseverance of these brave, saint-like people and extol their superhuman inner strength. Sirens instead shows how similar to other twenty-somethings Lilas and her band are: joking over drinks at bars, becoming irritated with each other, talking to a parent who seems not to realize you’re no longer a child.

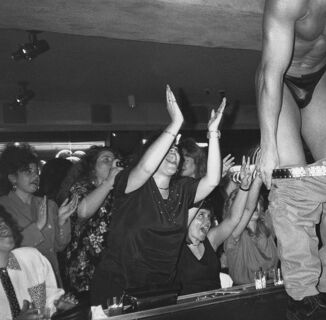

Lilas says early on that she started the band because everyday life was so uncertain, that she needed to do something besides her teaching music to young kids at her day job. At one point, she complains when she wants to go out clubbing that she has too many “teacher clothes”. Lilas is like many of us, far from Lebanon, who, after two and a half years of an ongoing pandemic are still making art, still working, still doing some queer socializing (including maneuvering around exes) as our countries continue to fall apart.♦

Sirens opens in theaters Sept. 30.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox