Well, that was fast.

On Thursday, September 27 – only nine days after Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, CA formally announced their new campus policy allowing LGBTQ students to date on campus, as well as the formation of Haven, an official LGBTQ support center – the board of trustees met to plan their response to the mounting pressure from conservative critics of the new policy.

The policy had been in the works for more than a year, with many sides of the LGBTQ debate considered, but the conservative backlash to the final decision moved quickly. In the nine days since the story broke, parents had threatened to withdraw their students from the school. Donors were calling and emailing and commenting on Facebook, refusing to give another cent until Azusa Pacific changed the policy. At least one faculty member demanded that university president Jon Wallace immediately resign. Right-wing and evangelical media outlets like the Christian Post, LifeSite, and the American Conservative had mounted a firestorm of criticism, claiming that the school had “caved” to liberal values and lost the meaning of its “God first” motto.

Just a day after the board’s meeting, with little to no prior warning given to the LGBTQ student community, the board of trustees released a statement officially reinstating the ban on LGBTQ relationships. In addition, the students on staff as Haven’s leaders must rename the office and receive board approval for any planned events.

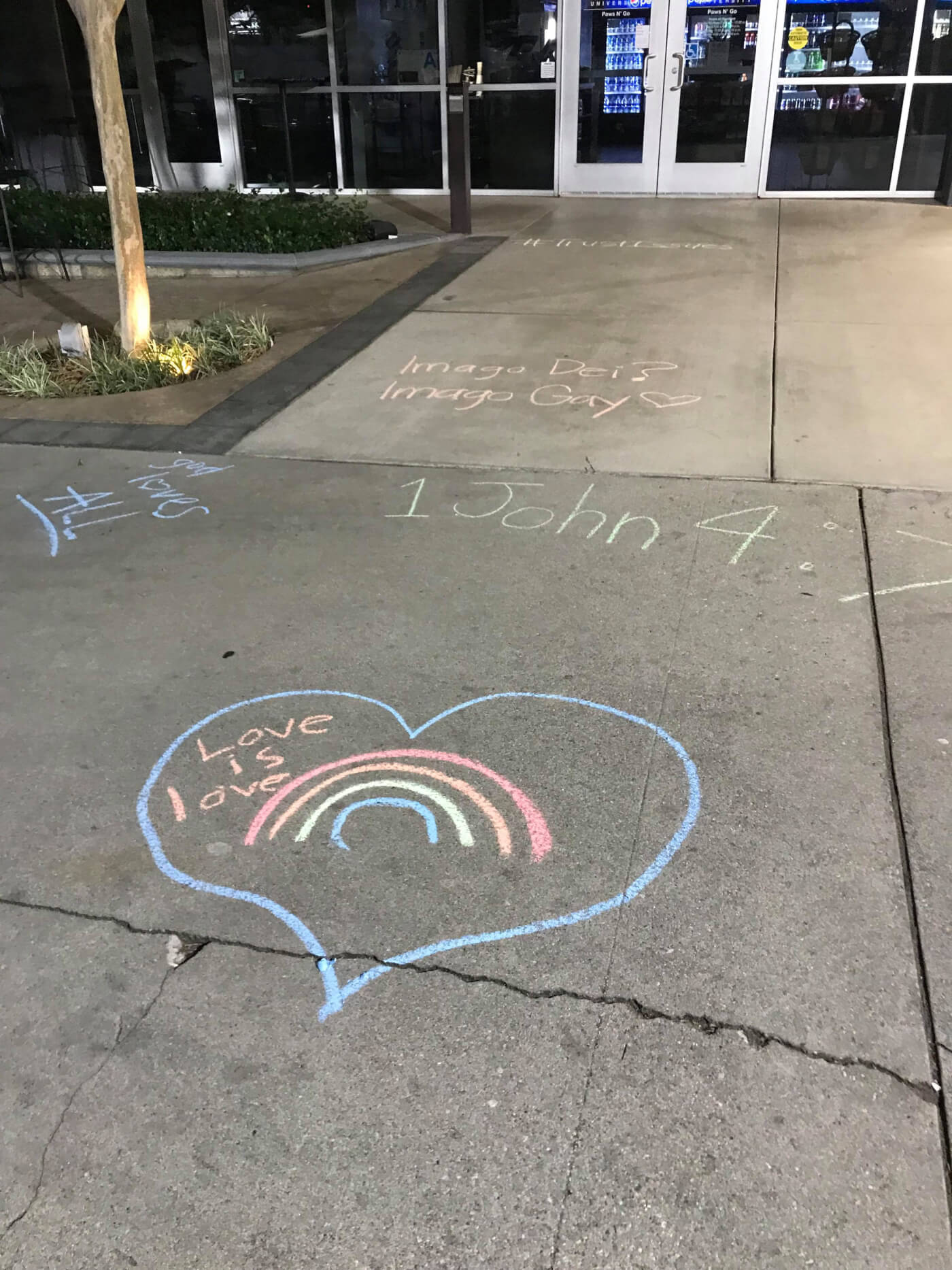

Alexis Diaz, a queer student at Azusa Pacific who previously praised the administration for their new policy of acceptance, quickly organized a protest in response. Overnight on Sunday, September 30, dozens of students chalked up the campus with rainbows and filled the grounds with sticky notes featuring LGBTQ-affirming messages. The following afternoon, on Monday, October 1, about 200 students gathered in front of the Richard and Vivian Felix Event Center to pray and sing in opposition to the decision.

“This decision didn’t really seem like it [was made] in the best interest of students,” Diaz said. “Things were happening at a hundred miles per hour, and it felt like we weren’t a priority. Like, ‘Oh, what’s the next item of business? Yes, let’s just go ahead and reverse that.’ It didn’t seem well thought-out.”

Diaz cites threats from donors and parents as a key reason the board decided to change the policy. “From approving the LGBTQ pilot program in the first place, it sounded like [the administration] had thought about it, and that felt really good. Now to have it switched around and to have all of these different terms and conditions under which we [LGBTQ students] can meet, it just feels like… outside factors made them think it was the wrong decision.”

Azusa Pacific University certainly is facing its fair share of financial problems. According to ZuNews, the school’s student newspaper, the university ended the 2017-18 school year with $10 million in debt, and in response, the university has cut $17 million of projected spending this year.

Despite this, the university denies that financial burdens played any role in the board’s decision. Rachel White, Azusa’s associate director of public relations, emphasized, “The board takes its responsibility to steward the mission of the university seriously, while staying at the table in dialogue about how to support all students. The board’s decision reflects its convictions and unwillingness to be swayed by any pressures.” White could not clarify whether these outside pressures included the LGBTQ students with whom the university had already been negotiating for over a year.

Similarly, in an interview with AirTalk, board chair David Poole declined to answer whether the board would ever reconsider their swift backtracking. “We remain firmly anchored to our biblical position that we have adhered to for many years,” he said, “but we are engaging and talking with the community about how we can best minister to them in the context of who we are as the university.”

A major concern for LGBTQ students now is whether those who opened up about their relationship status during the period in which the dating ban was dropped will now face disciplinary measures. Previously, students in a same-sex relationship faced “vague” consequences, according to Courtney Fredericks, one of Haven’s leaders. “If a student complained about two students being in a same-sex relationship, that would initiate a conversation [with administration],” she said. “If the accused students are in leadership, they’ll be given a choice of stepping down from leadership or breaking up.”

Fredericks has not yet heard from the board or administration about what will happen to students who now must go put their relationships back in the closet, but she expects a Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell kind of policy. “I think it’s most likely that students… will just be given a pass, that it will just be ignored,” she said. “It’s not like APU wants to go out and find students who are in relationships.”

Since the October 1 protests, students have not taken other steps to address the change. However, Erin Green, a lesbian alum of APU who helped craft the original policy change, insists that the fight will continue. She now serves as co-executive director of Brave Commons, a college-focused “intersectional, queer and POC-led Christian organization seeking to provoke a movement of faith and justice in the academy and beyond.”

“We’re taking a breather for a couple weeks and coming back with some serious energy around what we want to do. What’s in the works right now is a letter to the board and a petition… to show the extent of the support for the students at APU,” Green said.

While a letter and petition may build up a network of allies, Diaz questions what it will take for the board to listen to students. “Do they even care about student feedback if the policy reversal happened in the first place? I don’t know how much they actually care about what we’re experiencing,” she said. “I want to stay positive, but I think a lot of students are really guarded right now.”

And of course, beyond stubborn board members and angry donors, one of the greatest challenges the students face is time. Amidst organizing work, students still have to, well, study. And of course, eventually, students graduate and have the opportunity to build a life outside of a discriminatory campus. When the board can, in one afternoon, overturn a decision that was a year in the making, the four years students typically spend at Azusa suddenly seem very short.

Diaz, a senior, feels this pressure. While she’s not entirely sure what her post-grad plans hold, she remains committed to advocating on behalf of students that face discrimination. “Because I do really care about the university and what it has offered me, and because I do care about students who are affected by this policy, it would be hard for me to just walk away from that.”

Cayla Hailwood, another queer senior at Azusa Pacific, faces the same problem, but she remains motivated by the larger justice movement she sees happening in Christian spaces like the progressive Episcopal church she was raised in. She’s working with the student government association to craft a resolution in support of LGBTQ students. “God is moving within this,” she said. “We are seeing a shift within our generation of Christians. We are having Biblical Studies professors who study the word of God and are teaching about it with a very open interpretation of Scripture. More and more students are saying, ‘Let’s err on the side of love and not hate.’”

There’s much uncertainty about what the future holds for LGBTQ students at Azusa Pacific, but one thing seems clear: LGBTQ and ally students and alumni are done with just talking. They’re ready to act. “David Poole said… more dialogue is a part of remaining anchored and centered in Christ. Well, I think we’ve heard enough dialogue,” Green said. “We’re done talking. We’ve lost trust in the university and their capacity to handle discussion. So the next steps are action because if we just sit around talking, we’re not going to get very much done.”

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox