Ryan Kendall knew that change wasn’t possible. But after his conservative parents discovered Kendall was gay when he was 14, he didn’t have a choice but to try.

After Kendall’s parents read an entry in their son’s journal where he had come out to himself, they signed him up for what’s known as “conversion therapy.” That term refers to the widely discredited practice of seeking to rid LGBTQyouth of their same-sex desires. Once a week, Kendall had therapy sessions over the phone with the late Dr. Joseph Nicolosi of theNational Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH), and sometimes they would meet in person.

Widely referred to as the “father of conversion therapy,” Nicolosi was deceptively warm. Kendall remembers him as frequently wearing a pink sweater with fluffy cotton balls on it. In Nicolosi’s Encino, Calif. office, he had a stack of Highlights magazines on his desk.

“I think people expect conversion therapy advocates to be sinister, but it’s almost disarming how well-meaning they can come across,” Kendall told INTO.

In their sessions, Kendall claims that Nicolosi would use “fear tactics” to try and scare him out of being gay. The doctor allegedly warned him that because society stigmatizes gay people, he would be discriminated against for the rest of his life. Kendall remembers being told a litany of “disinformation” during these sessions, including that the average life expectancy of gay men is 30 years old. He says that Nicolosi told him if he didn’t choose a different path, Kendall would get AIDS and die.

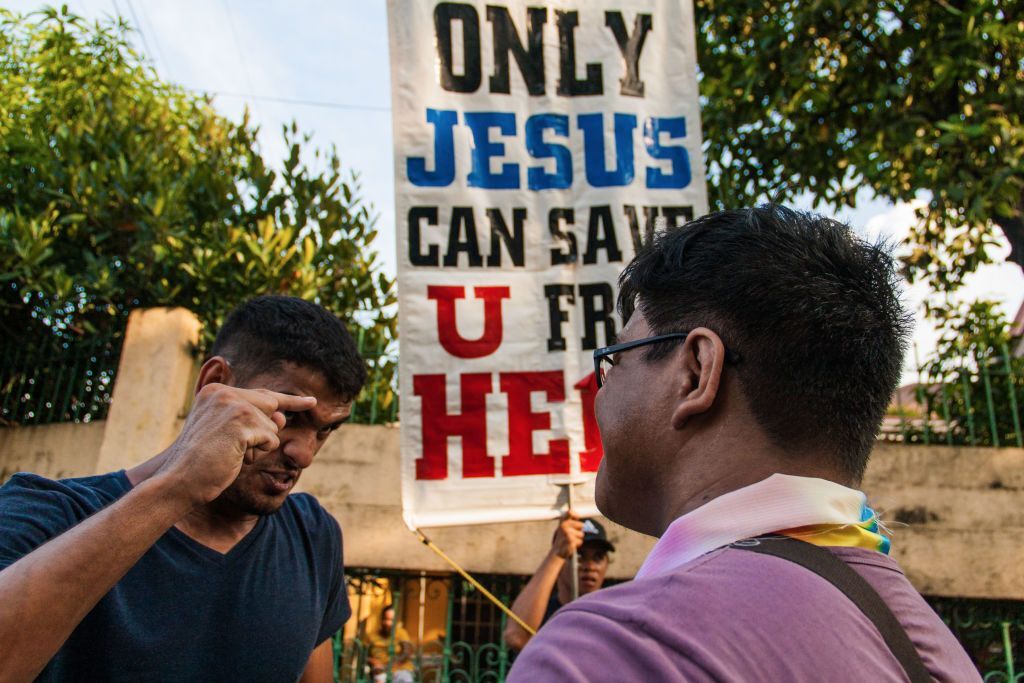

The end goal of these sessions, as Kendall explains, was to get him to blame his parents for his homosexuality. That made a bad situation at home even worse. When his mother learned that her son was gay, she told Kendall that he would “burn in hell.” Even as he was seeking treatment, Kendall claims that his mother continued to call him “repulsive” and “disgusting.” He frequently ran away from home.

“My mother once told me that she would rather have an abortion than have a gay son,” claims Kendall, who later filed for custody of himself to get out of the situation. “Conversion therapy does damage that lasts a lifetime. There is no undoing the harm that was done. It tore my entire family apart.”

A bill recently re-introduced in Congress seeks to ban this harmful practice, which is already illegal in California, Illinois, New Jersey, Oregon, and Vermont. Known as the Therapeutic Fraud Prevention Act, the bill is being sponsored by Sens. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.), as well as Representative Ted Lieu (D-Calif.). In a statement, Booker claims that the practice “isn’t therapy at all.”

The Senator continues, “It’s a torturous, fraudulent practice that has repeatedly been condemned by medical professionals and has no place in our country.”

America still has a long way to go in making conversion therapy a thing of the past. Despite the fact that the practice has been condemned by groups like the American Psychological Association and the American Counseling Association, it remains widely employed around the United States. The Family Acceptance Project, a research and policy initiative based out of San Francisco State University, estimates that 1 in 3 LGBTQpeople are subjected to this harmful treatment at some point in their lives.

“There are hundreds of unlicensed conversion therapy camps across the country,” says Kendall, who sits on the advisory council of Born Perfect, a national effort to end the practice. “It’s being practiced in probably every county and every city.”

In addition to the 41 states that continue to allow it, conversion therapy was covertly endorsed by the Republican Party last year. At the 2016 Republican National Convention, the GOP added language to its official platform supporting “the right of parents to determine the proper treatment or therapy, for their minor children.” That thinly veiled rhetoric wasreportedly pushed by Tony Perkins, president of the right-wing Family Research Council, who has long been a vocal supporter of conversion therapy.

Sen. Murray warns that the Trump White House could further Perkins’ extreme anti-LGBTQpolicies.

“The Trump Administration has laid out a hateful, damaging agenda to undo hard-won progress, divide our communities, and hurt our friends, neighbors, and family members just because of who they are or who they love,” she says in a statement.

But as conversion therapy survivors told INTO, trying to change the orientation of LGBTQyouth doesn’t work. The practice leaves its patients with decadesif not a lifetimeof trauma. Many reported attempting to take their own lives as a result of the severe emotional and psychological anguish inflicted.

Survivors argue that it’s time to outlaw conversion therapy once and for all.

NARTH is just one of many “ex-gay” groups that purport to help people cure their homosexuality. The earliest such organization, Love in Action, was founded in 1973 by Kent Philpott, John Evans, and Frank Worthen after the American Psychological Association elected to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness the same year. Evans would later leave the group in 1992 after a gay friend took his own life.

He would later tell the Wall Street Journal that Love in Action, which was renamed Restoration Path in 2012, was selling false hope.

“There’s a part of you that knows it’s completely insane,” says Garrard Conley, a conversion therapy survivor who has since written a book, Boy Erased, about his experiences. “And then you think that maybe you’re the crazy one. That’s how brainwashing works.”

Conley, who grew up in a small town in the Ozarks, was outed to his parents when he was 16. The news was difficult for his family to take in. His father had recently been ordained as a preacher. Conley’s father was asked during his swearing in ceremony: “Do you renounce the sin of homosexuality in the church?” Conley was in the audience, looking directly at his father, when his dad placed his hand on a Bible and said “yes.” The church recommended his father send Conley to Love in Action, which was located in Memphis, Tenn.

He went because he wanted to make his parents happy.

Conley, now 31, claims that after arriving at Love in Action for a two-week session, counselors took away a Moleskine notebook in which he wrote short stories. They tore out the pages right in front of him, wadded them into a ball, and tossed them in the trash. Staff members claimed his notepad was a “distraction.” Conley says that Love in Action, an inpatient facility that operated four centers, wouldn’t allow its guests to have doors on their rooms, which meant that residents didn’t get a moment’s privacy.

The sessions at Love in Action, Conley claims, were focused around isolating the root causes of patients’ homosexuality, which was viewed as a product of others’ ungodly behavior.

Although Nicolosi’s treatment relied on the Freudian model of a distant father and an overbearing mother, Conley was instructed to map out a Genogram of his family tree. He drew “sin symbols” on the tree to denote to his relatives’ various transgressions. There was a different code for each sin. The abbreviation for abortion was AB, but if the family member in question was addicted to gambling, that would be marked by a dollar sign next to their name.

In another workshop, Conley says that he was placed across from an empty chair and forced to scream at his father for making him this way. “You did this to me, daddy,” he would yell at nothing.

Wade Lee Richards, who ran away from home as a teenager, came to Love in Action when he was 17. He was living in a homeless youth shelter in New York City at the time and didn’t have many other options. The staffers initially turned down his application, saying that he was too young for the programming to be effective, but Richards insisted.

“This is life or death for me,” he recalls telling the admissions team.

Richards describes the year and a half he spent at Love in Action as “living in hell.” After he arrived at the Memphis campus in 1998, staffers confiscated all his name brand clothingincluding his Calvin Klein underwear. According to Richards, administrators told him that designer labels instilled a “false identity of femininity.” Instead, Love in Action reinforced traditional gender roles by sending their male patients to local high school football games and teaching them how to change the oil in a car. The women received makeup tutorials from a Mary Kay representative.

“Their agenda was to break me in any way they could so they could fill me with their ideas about who a man is,” Richards claims.

As part of his therapy, Richards says he was forced to write to all of his old friends, breaking off their friendships. The 38-year-old further alleges that his mother flew in from Wisconsin so he could scream at her in front of everyone, telling her this was her fault. But it was the isolation that really got to him. Love in Action gave residents a detailed map of how far they could wander off campus, and residents were restricted within a certain radius. They weren’t allowed to go to the mall. If residents went to a public place, they had to take multiple chaperones.

“We were living in a bubble,” Richards says. “I remember thinking that’s what my life was going to be likeloneliness.”

Conley, who said that he is still working to deprogram the toxic messages he learned in conversion therapy, struggled for a long time with happiness. It was difficult to be intimate with another man. Conley said that when he would touch his boyfriends, he could feel a burning sensation, like the flames of hell rising to the surface of the skin. Brad Allen learned the same lessons after seeing a conversion therapist in Denver for three and a half years. The 36-year-old was told that his homosexuality “comes from a deep insecurity” within himself, that Allen was drawn to the things in others that he feels he lacks.

“I believed that if I were truly to ever have sex with a man, that I would destroy him,” Allen explains. “I thought my love was toxic.”

Allen, who lived in a fundamentalist Christian cult until he was 18, planned to die by suicide in 2012 after developing feelings for another man. He felt that he needed to “save” his partner from loving him. But a few days before he was set to follow through on his plan, Allen says that the “darkness in [his] brain parted,” and he heard a voice from inside himself saying that there was nothing wrong with him. He was not toxic.

“That saved my life,” Allen claims. “I have never been suicidal since that day because I refuse to listen to anything that tells me I’m toxic.”

According to theHuman Rights Campaign, these experiences are common among survivors of conversion therapy. The LGBTQadvocacy group reports that youth who have undergone these practices, which sometimes include shock therapy and exorcism, are eight times more likely than their peers to have attempted suicide. HRC also claims that survivors are six times as likely to experience extreme depression as a result.

“Conversion therapy kills,” claims Kendall, who has since become one the nation’s leading voices in the movement to outlaw it. “It kills children and it kills adults. It does so by destroying their sense of worth. There’s no way to escape the message that who you are is wrong and bad, especially when it’s children.”

If survivors say that conversion therapy is harmful and deadly, 2017 could prove a watershed year in the push to ban the practice, which is sometimes referred to as “reparative therapy” or “sexual orientation change efforts.”

Samuel Brinton, a conversion therapy survivor, is behind the “50 Bills, 50 States” effort, whose goal is to introduce legislation to strike down conversion therapy in every state in the nation. Bills have already been proposed this year in places likeConnecticut andNevada, as well as at least 19 other states. Many of these legislative efforts failed, but others may soon become law. A bill to outlaw conversion therapy for minors has been introduced in the Colorado General Assembly, where itwas approved by the House in March.

Earlier efforts in the state have failed, but this year’s bill may pick up steam if the Congressional effort gains traction.

Amber Royster, the former executive director of Equality New Mexico, was a major force behind the conversion therapy ban in her state. New Mexico became the sixth state to outlaw the practice earlier this yearthe first of many dominoes to fall in 2017.

As a survivor of conversion therapy, Royster understands the grave abuse LGBTQyouth are subjected to in a fruitless quest to change their orientation. She experienced severe PTSD and depression as a result of the year she spent in anti-LGBTQ counseling at her church; she says that her family was “torn apart” by the experience. After she got out of the program, Royster left home for 15 years barely speaking to her parents.

Royster knows that bills like Nevada’s won’t stop conversion therapy, but she says that lawmakers have the ability to “send a message that the state views this as harmful.”

“It’s a part of a culture shift,” she says. “We know that passing laws doesn’t change hearts and minds, or otherwise there would be no more homophobia after gay marriage became legal. We never rely on policy as being the end-all-be-all solution, and the fact is that we still can’t regulate pastors. But it gives us a mechanism to hold licensed practitioners accountable.”

In addition to pushing state and national legislation, advocacy groups like Equality New Mexico and the Born Perfect Campaign are working with state welfare agencies, social workers, and foster and adoption agencies to create the kind of cultural shift necessary to ensure that no child ever has to face this form of extreme abuse. Kendall hopes that these laws get the word out to parents and children in the meantime that conversion therapy is “dangerous and ineffective,” which he says will keep others from experiencing what he went through.

“Conversion therapy victimized all of us,” Kendall says. “I know from first-hand experience how close it came to killing me.”

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox