Last week I flew from Burbank, California over the mighty spine of the Rocky Mountains before landing on the flat plains beside Denver International Airport.

On the short two hour flight, my face was pressed against the window, especially towards the tail end of the trip, when massive groves of aspen trees lit up the chiseled peaks of Colorado like brightly colored confetti.

Electric yellow, atomic tangerine, and bright fire-truck red.

Enthused by the vistas from 30,000 feet, my little tree-hugging heart was overjoyed and yowled nothing but YAS!

Aspen trees (Populus tremuloides), after all, are known affectionately to a quirky few as YASPENS because when they flutter their thousands of leaves together in the breeze and turn gold in autumn, it’s hard to say anything but YAS and WERK BITCH, and maybe even, COME THROUGH YOU QUAKING BEAUTIES!

Living in Los Angeles for the past two years—a seasonless time capsule of aggrieved sublimity—I haven’t had the chance to peep the famous autumnal spectacle I’ve cherished since I was a boy growing up in Colorado.

Seasons, everyone complains in southern California, I miss them.

I knew shortly after sniffing the crisp Rocky Mountain September air and driving the swelling I-70 west over the many colorful mountain passes towards Vail that it was time to hike myself right into a grove for some up close and personal leaf peeping.

Leaf peeping?! You ask. What is this ridiculous term?!

The thing is, I’m sure you’ve leaf peeped before without even knowing it (and fuckin’ loved it). Now you know it’s a legitimate (though seasonal) hobby. But if you’ve never leaf peeped, or if you’ve never even heard of the frivolous term, then now is the time of year to give it a dabble.

Leaf peeping is the pumpkin spice latte of the eyes and the decorative gourd of the soul. It is the autumnal turtleneck sweater of visceral experience.

It’s easy, too.

All you have to do is go outside and stare at big, fluffy, deciduous trees whether you are in New England or New Mexico or anywhere else.

On my first full day in central Colorado, I rose excited for leaves.

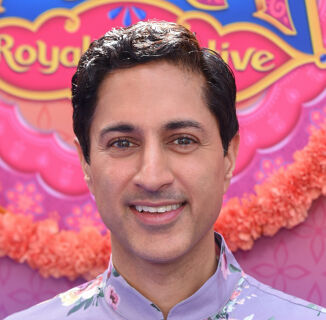

I met up with my longtime friend and fellow leaf peeper, Anna Suszynski, a favorite co-adventurer from college days. Together, we’ve explored magical realism in the Mojave, face-numbing powder days on skis, and canyons under untamed meteor showers.

Anna knows full well the magic of the American West, as well as the natural world at large. She’s a writer who humanizes every being. She is especially fond of Colorado landscapes and their popular YASPEN trees. She brings her own magic with her everywhere she goes—or maybe it just follows her.

We converged with a hug early in the morning at a trailhead called Whiskey Creek by the side of I-70 between the local mountain towns of Minturn and Avon.

The trail we followed was one made for mountain bikers, but it was shared generously by all. It followed a steep, swerving line uphill through the tall grasses and woody shrubs until it gave way to an open prairie surrounded by YASPEN.

Before us, against a robin-egg-blue sky, the deciduous trees were dancing their little hearts out as they lost themselves in the nippy morning breeze.

The fluttering sound the trees’ leaves make in the wind has given them their informal name of quaking or trembling aspen but I don’t agree with these adjectives.

They imply anxiety, frailty, and tremendous unease. YASPEN are not these things—YASPEN are confident, at ease performers.

The flutter of their leaves is a sensational mountainside melody. Visually, the trees are enthusiastic dancers serving fiercely energetic jazz hands—flamboyant fingers fluttering for that over-the-top, super-glam effect. The groves in wind are a dance troupe that has all of Broadway quaking in their kinky boots.

Midway through the peep-sesh, we entered a mature grove.

The tall and thin mid-sized YASPEN giants beside their evergreen friends swayed lovingly from side to side.

The trees are love-hearted leaf havers and white-barked beings whose trunks have hundreds of coal black eyes that watch you carefully as you walk among their family.

One of the reasons we all love the YASPEN is because they are trees of community.

In that way, they aren’t unlike our extended queer family.

Each clonal grove is a single organism connected by the roots.

While each tree may look like its own individual being, the organism grows and progress and endures life as one.

When one single tree dies, the entire grove notices, feels, and mourns its lost sibling.

The oldest YASPEN colony in the world, the mighty Pando, lives in South-Central Utah and covers 106 acres.

It is said to be possibly the heaviest organism in the world, and perhaps the oldest, too, at an estimated 80,000 years old.

Pando is sadly dying and we don’t know exactly why.

If I were to guess, it would probably rhyme with schmimate schmange.

I’m not sure of the age or health of the colony Anna and I witnessed dancing above the Vail Valley of Colorado, but I can assure you like all YASPEN groves I’ve visited, this one felt especially ancient and wild.

Beneath the trees the golden grasses had been flattened by sleeping elk herds. Grey jays and western bluebirds zipped about and a couple of times on the trail, we came across the color scat of the black bear.

YASPEN are home to so many.

The eyes on the trees watched us and the birds and the winds loosened their bright yellow leaves on our backpacked selves before they dropped to the musk ground. The ground that was already beginning to swallow them before the snow prepared to cover them.

By mid-October, the trees will lose all of their leaves and transform from wonderfully fluffy friends as shaggy as a lion’s mane to dormant, striped trunks.

It is this ephemerality that makes us love them so.

It is the same ephemerality that makes us love the summer’s wildflowers and the winter’s snow. It is only in the limited-edition that we miss what we once had and appreciate what we once saw.

Especially trees, our life givers.

Our carbon dioxide killas, air suppliers, our life givers.

As Anna and I walked among the mature grove we looked nowhere but up as the leaves as fluttered against one another like little tambourines.

The sound is indescribable- but I will make an attempt.

It is a like a little stream rushing in spring, only softer. It is like a rain stick turned upside down, only gentler. It is the cool voice, singing you into submission.

Hermann Hesse, the Nobel Prize-winning poet once wrote these famous lines on our friendly living giants—“when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy.”

As we listened, I remembered I’ve been communicating with the YASPEN my entire life.

They are another extended family, a comforting chosen family.

I’ve always entered a grove politely, like a guest taking off their shoes before stepping into an acquaintance’s living room.

I’ve always respected the trees, once stopping a lovestruck couple who once thought that gouging their initials framed by a heart into the soft delicate wood of the trees was acceptable.

I have always played with the trees, and I know Anna has too, for in that stand we resorted to childhood tricks and gathered many of their fallen leaves into big fistfuls before tossing them back into the air for a second wind.

I know we have always played with the trees because we hugged their white trunks that whitened our bodies with their powder and swayed in the gusts with our hands twinkling in the air.

In the YASPEN, we can play and be a part of a family even when we are alone.

We can feel all of the beauty even when we feel like we don’t have any of it.

We can skip through them and beside them in the tall grasses of the subalpine and montane like Anna did, sprinting, catching bright yellow leaves loosened by the wind as they were strewn across the mountain landscape.

Or as Anna said to me after the hike-

“They are like groups of breathing communities that live together so close.”

I’m thinking of Anna holding one of the leaves up to the stupidly blue Colorado sky, a leaf that was yellow, and orange, and a little bit green.

“We could be like that in the future, Miles.”

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox