A Scandinavian gloom settled over Norway’s capital city and my friend Frida and I pierced through it on city bikes like arrows. As a local Oslo-ite originally from the the untouched lands of the country’s Lofoten archipelago, Frida was used to inclement Norwegian drear and so the the two of us spoke of sunnier times. A few years ago we met below Cape Town, South Africa’s glorious Table Mountain, where we spent our off time from our study abroad courses exploring the mountain’s many ravines.

Reconnected years later on my short Norwegian jaunt, we were braving the chilly rain to visit one of Oslo’s most popular tourist attractions: the Vigeland Installation at Frogner Park.

Before my trip, I had never heard of the sculpture park, and I’m surprised I hadn’t—it is currently the largest sculpture park in the world by a single artist and receives over a million annual visitors. The 1942 installation was funded by the Norwegian Bank and contains 212 statues that blanket some 80 acres of Oslo’s Frogner Park; a place of hills, pathways, public pools, and ponds.

Frida and I dropped our bikes by the park’s entrance and dawdled across the long quad to the the Vigeland Installation. Among the melancholy of elements, the sculptures of humans far in the distance stuck out like sore thumbs in their bronze and granite brilliance—not to mention their nonchalant nakedness in contrast to the bundled and Gore-Texed tourists.

On the barrier and railings of the installation’s commencing bridge were 58 bronze statues of men, women, and children. Many of them were frolicsome, like the statue of the man piggybacking his son or of the handsome athlete with his arms stretching ebulliently to the sky. Others showed what appeared to be same-sex intimacy, like the statue of one girl cradling another, or the one of two men locked in a lustful look. And then there was the bizarre, like the angry and lone toddler throwing an epic temper tantrum—or the most wicked, one of a man being attacked by four flying babies.

This first set of bronze bridge sculptures served as an introduction to the park and showed some of Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland’s (1869-1943) main themes: humanity, relationships, and the circle of life. By displaying the figures nude (and without naming any of his works) Vigeland achieved a timelessness reminiscent of Greek marble sculptures, each obliging the viewer’s interpretation.

The night before we visited the park, Frida and I had cooked dinner for her collection of close friends (to name a couple, there was Kristine who had just arrived by train from a surprise weekend in Stockholm with her boyfriend, and there was Anders who as a teen once flew on skis as a jumper.)

As our night wound down and we drank Norwegian lagers, I began researching Vigeland’s Installation and found images of the statues. Besides the statues of heteronormative relationships and families, there were also a few naked men wrestling and naked women caressing one another. But despite many of statues’ obvious homoerotics, very few had validated their queerness.

I did, however, find that many critics of the installation said it expressed misogyny and fascism and had consequently painted Vigeland as Nazi-sympathizer akin to German artist Arno Breker. And while earlier reports and stories of the statues found the statues disturbing — French/Danish/Norwegian art critic Pola Gauguin said in 1945 that the installation “reeks of nazi mentality” — others, more recently, have not seen the sculptures as brutally.

Many were emotionally inspired, like Washington Post writer Jennifer Moses, who said of the installation in 2016: “All I can say is that you have to see it to believe it…You stand there staring, jaw dropped, tears flowing.”

The Daily Mail expressed neither abhorrence nor astonishment with the collection, naming the works “the weirdest statues in the world.” I slept excited to gather my own interpretation.

Frida and I spent the least amount of time in the park’s second section, the fountain that was once designed for the Norwegian Parliament, Eidsvolls Plass, but instead became one of the centerpieces for Vigeland’s installation. Here, a massive sculpture of muscular men held up a giant cascading bowl, while statues of children played in trees on the fountain’s perimeter.

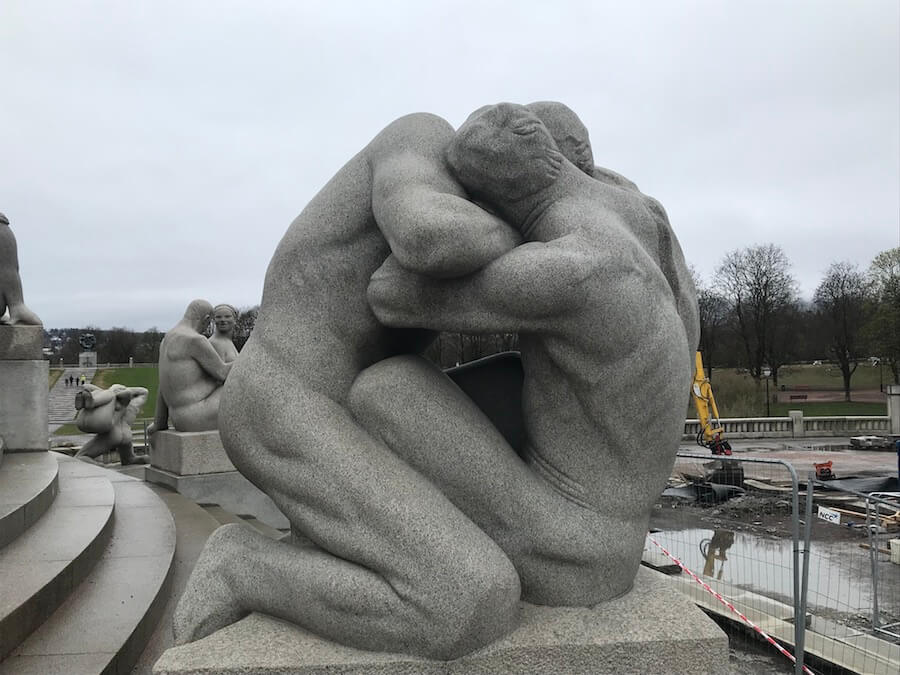

We climbed the stairs beyond the fountain high into the park’s most iconic section, where 36 statues composed of iddefjord granite from the west coast of Sweden circled a towering monolith composed of 121 bodies of men, women, and children; young and old, strong and weak.

This high plateau of the park however, was guarded by a circling series of iron wrought gates decorated by male and female group nudes—though they were always separated by gender. One of the gates contained six men, and appeared to be a sort of precursor to later Tom of Finland sketches (another controversial character, like Vigeland, who eroticized Nazis in his early work), evidenced by their identical hypermasculine builds highlighting muscular buttocks, barreled chests, and bulging calves, as well as for their communal nudity and close proximity to one another; they are touching each other and smiling. On the iron wrought gates with women, two separate naked trios lock arms and smile as their long hair full of flowers flutters in the wind. But these gates aren’t the only homoerotic works in the park.

Among the 36 granite statues at the center of the park, I found three statues of women in close partnership: the first two young and naked women play and contort their bodies into a ring, a second nude pair shows a woman with her arm slung affectionately over another woman, and in the third, an older woman cares tenderly for another.

And alongside these women are plenty of male/female couples (some in throes of love, others in violence) as well as a statue of two children riding their mother like a horse (and using her braid as a bit), as well as a skinny elderly man squashed between two old women, and one statue of two muscular men caressing each other so closely, you can’t tell if they are kissing or quarreling.

Queerness is portrayed not only in bronze and granite at the installation, but also in wrought iron gates. Of the nearly 212 statues and gates, there are same-sex couplings and homoerotics portrayed in about 15 of the works—depending on how generous or strict you are with your interpretation. But it ends up being below 7% of the sculptures, not far off from the self identifying statistics on the percentage of queer people in the world.

Vigeland’s attention to idealized male bodies, genitalia, and over the top musculature shows his preference for the male body—it is an ode to hypermasculinity. But the anatomical realism of many of his male statues only adds to the homoeroticism of the same-sex statue pairings.

In the middle of the high plateau of statues is the installation’s most famous work: an obelisk composed of 121 nude human bodies shooting 45 feet upwards.

As Frida and I milled around the statues, I kept coming back to the monolith. For in it, I see the critics’ interpretations of historical abhorrence as well as modern day amazement .

I observe the crushing weight of a society piled upon each other with only few benefiting and I understand the terrifying comparisons by critics to footage of the mass graves of Holocaust concentration camps, but I also see inspiration. Although the figures are locked in granite, they appear to be alive in animation— a mix of bodies, genders, orientations, experiences, and spirits struggling through the difficulties of existence but simultaneously emboldening each other skyward.

What do you see?

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox