Even in an age when sharing mundane details online is standard, it’s easier than ever to control the way others see us—until, as people often say on social media, someone gets “exposed.” Welcome to Exposed, a monthly column where author and activist Chris Stedman invites you to get a little more vulnerable.

Noah pulled up Twitter and began drafting a joke about poppers. Once he got it just right, his fingers hovered just above the keyboard as he set about the hardest part of any tweet: deciding which account to send it out from.

For years, Noah maintained two accounts on Twitter. The first he’d used since high school; it was a place for more personal posts, and he would alternate between locking it down to maintain privacy and making it open for anyone to see.

The second was born when he was in college and working with a program for high school sophomores. The organization required that he and other counselors engage with their students on social media, and Noah felt uncomfortable using his personal Twitter account, where he had posted both earnest personal struggles and salacious jokes about his involvement in kink communities for years. So he made another one that felt more “professional.”

After the program was over, he decided to carry on using his new account and anonymize the original.

Private social media accounts, often referred to as “alt” accounts on Twitter or “finstas” on Instagram, are nothing new. Since the beginning of social media, people have created secondary or secret accounts — like a private Xanga account for publishing anime fanfiction, or a secret MySpace account for sharing in-progress music — where they can post a bit more freely without having to worry about the possible judgment of onlookers like family members, coworkers, or prospective employers. For some, part of the appeal of having two accounts is the freedom to curate and select who gets to see what.

Though I don’t have an alt account, I see the appeal of maintaining a private account. For years, I kept my Twitter account very clean. Afraid of doing damage to my public activism by revealing something personal that might alienate colleagues, I primarily used my account to post updates about my work and some safe personal reflections.

But I still needed outlets for the things that felt a bit messier: for thoughts-in-development, impulsive reactions, frustrations and fears, and edgier humor. Whenever there was something I felt I couldn’t tweet, I would DM or text it to a friend, sometimes even suggesting they post it themselves if they wanted to. On occasion, they would, and as I watched people respond to my words posted on someone else’s account, I wondered what it might feel like to post a little more freely. I’m now a lot more unfiltered on Twitter, but back then I probably would have benefited from having an alt account.

For years, Noah maintained both of his accounts, and they had very clear delineations: one was for engaging with work colleagues, while the other was more intimate. On his anonymous account, he felt freer to be humorous, sarcastic, or to like tweets from accounts posting sexual content without it showing up on someone else’s timeline. He felt more able to show up online as he would with friends on his “personal” account, whereas his “professional” account was a place for how he thought he was “supposed” to be—how a future employer would want to see him. It felt like he was practicing “dress for the job you want,” but for social media: “post for the job you want.”

Yet while the existence of his alt account made him feel more able to post online without having to totally filter himself, he couldn’t help but feel like his online self was split in two. Still, it felt like a necessity, and it was better than not being able to share some of those things online at all.

But earlier this year, something happened.

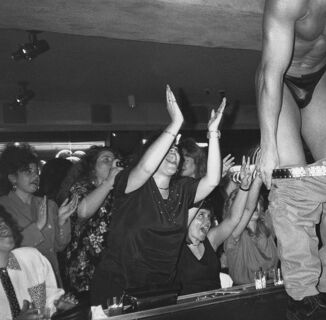

On New Year’s Eve 2017, Noah went to the closing party for an iconic bathhouse in Chicago. Prior to attending, he’d read an article about it for a class, and when he arrived, he bumped into the author of that piece. They chatted for a bit, winking and flirting before parting ways.

Later, after the party had ended, the writer contacted him on Grindr and asked if Noah would be willing to give him a quote for a piece he was writing about the event. For Noah, a Master’s student studying kink communities, it felt like an exciting opportunity to be cited as an academic authority in an article on queer sexual history. But the writer ended up saying he didn’t have time to call Noah for a quote before his deadline, and the conversation turned sexual before fizzling out. Noah didn’t hear from him for months after that.

But in February, a friend sent Noah an article about the closing party, written by the person he’d met. It had been published two weeks beforehand, and to Noah’s astonishment, it contained a quote he immediately recognized as his own. While he wasn’t named, Noah was shocked to see that something he’d said at the party — just a casual, flirtatious comment not intended for publication — was misquoted and attributed to an attendee matching Noah’s physical description. As he read it over a second time, Noah felt himself getting heated in a very different way than he had at the bathhouse.

Noah immediately logged on to Facebook and accepted the friend request the writer had sent a month back, and moments later the author messaged him saying he had quoted him in the piece — an attempt to make it seem like he was just reminding Noah of something they had already agreed upon.

Noah hadn’t agreed to be quoted, however, and he was sure the writer knew it. So Noah went to his personal Twitter—which had previously been primarily for private commentary — and drafted a post calling out the author and exposing himself as the person quoted. His account now unlocked, he posted a series of tweets. Within hours, he heard back from an editor at the outlet who wanted to address the situation.

Noah had learned from mutual friends that this writer had previously quoted others without their consent and realized that he was in a position to call out this behavior. But in the process of standing up for himself and others, Noah also realized how useless the barriers he’d been maintaining were — and how intimately intertwined his work and life already were. He could use his privilege to come out as a kinky person who attends bathhouses in his free time without risking his livelihood and without it being a huge surprise to anyone in his academic or professional spheres. Not everyone who had been quoted by that writer without their consent was in the same position.

He also saw breaking down the barriers he had constructed in his social media as an opportunity to push back against broader harmful narratives that stigmatize certain sexual practices. As someone who both studies and participates in sexual communities that have been marginalized and demonized, he was always uncomfortable with the veneer of “professionalism” he thought he had to maintain. In a way, it felt like doing so contributed to the respectability norms that marginalize the communities that Noah both studies and participates in. After speaking out about the article, he realized he was in a position to challenge that oppression by bringing more of his involvement in those communities into his social media presence.

Even though I think privacy is important, I’ve also found myself censoring things I wanted to post out of fear of what people might think about me. Having worked in higher education and been involved in building coalitions across lines of religious difference, I have often worried about how I conduct myself online — feeling I needed to be kind and patient, never petty or flippant, even when dealing with trolls.

I’ve also felt like I was walking a tightrope that enabled me to talk frequently about being queer, but almost never about the sex in my sexuality. It wasn’t until a couple years ago that I even tweeted the word “Grindr” for the first time.

But over the last few years, a bad breakup combined with a career change, cross-country move, and significant health issues caused me to reassess how much I was editing myself when posting online. I then decided to stop worrying so much about these boundaries. Now, when I notice myself wondering if something is “appropriate” to post, I try to push myself to post it anyway. I’ve become less interested in projecting a particular image, and more interested in trying to show up in the ways I want to. And while I’m sure some have hit the unfollow button after seeing a joke tweet about tops and bottoms from me in their timeline, I also enjoy using Twitter much more now and find myself making more meaningful connections through it.

Noah felt similarly and so, after the incident with the article, he decided to merge his accounts. Today he just uses one. Shortly after this switch, Noah presented at an academic conference, and he included his Twitter handle in the slideshow. When he got home, he noticed that his advisor and several former employers had followed him.

But he’s no longer concerned about controlling who gets to see what, and as a result, he feels significantly more open on social media in general. Even on Facebook, where his posts are much more likely to be seen by family members or old childhood friends, Noah has loosened the strings a bit. For years, he heavily relied on the list feature, which allows you to publish posts to specific lists of people while hiding them from others. For example, he had a “queers-only” list, but sometimes things would slip through the cracks, and eventually, he was exhausted by having to maintain these lists. So he finally let them go.

Now, whenever he posts on Facebook, anyone on his friends list — including his mother, old high school teachers, or distant relatives — can see it. Sure, it’s resulted in a few more conversations with his mom, like when one of her friends saw a photo of him at IML. But to Noah, swapping the discomfort of splitting himself in two for the occasional uncomfortable conversation with his mom is a worthy trade.

Want to get exposed? Email Chris at [email protected] with a short description of a time when you felt truly vulnerable — in either a positive or a painful way (or both).

Want more? Check out the previous installment of Exposed.

Image via Getty

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox