Two years ago I got married because I watched my mother die in front of me.

One morning in July, I got a call from my grandmother saying my mother had a brain aneurysm, and she was in a coma. The next day I booked a plane ticket to Cincinnati. I sat with her in the hospital for a week, painting her toenails and taunting her in the hopes that she would wake up. I would tell her that all her favorite ghost hunting shows got cancelled and that Julia Roberts wasn’t that good of an actress.

But four days after she was checked into the same hospital I was born in, her doctor told me she wouldn’t be waking up. As her next of kin, I had to make a choice: to prolong her life by keeping her on oxygen or allow her to die a natural death. Six days after I first walked into her hospital room—not fully understanding the gravity of the situation until I saw her deceptively cherubic face hooked up to a snarl of translucent breathing tubes—I held her heavy hand as she gasped her last breath. She fought hard for it; she always was a fighter.

The situation was difficult, but the choice wasn’t. Twenty-five years earlier, my mother had given birth to two little boys who weren’t built to survive. Their bodies slowly swelled like fever balloons from a disease so rare no one else has ever had it. It’s as if they were being boiled from the inside.

She had to make the same decision—twice. One was two and a half years old when his tubes were disconnected, the other just six months.

I gave her the gift she had given them so many years before: a freedom from pain disguised as suspended animation. Her face may have looked peaceful lit up like silvery gossamer in the too-bright lights of the hospital room, but she knew there is no peace in purgatory.

I married my husband because I needed to know someone could make the same decision for me when the time came. The incidence of familial intracranial aneurysms is up to 20 percent: meaning that as many as one-fifth of people whose parents or immediate family members have a history of violent brain trauma will experience the same. It would be more than a year before I got test results back saying my brain map was perfectly ordinary—no abnormalities. But in the heat of funerals and answering condolence cards, we had to act quickly.

My husband and I got married at City Hall in October 2016, and the photos we took that day look more like the cover art for a somber indie band than a ceremony marking our eternal love and commitment. We knew we wanted to get married from our very first trip to Coney Island two years earlier, locking arms on the Electro Spin to keep from being hurled into space. It wasn’t, however, exactly how we pictured getting married.

I never expected to tell this story in public—or at all. It was something that only we and a few other people knew. It was private enough that nearly a year later, I proposed to him a second time—this time in front of close friends with a sand diamond my great aunt brought back from Saudi Arabia when I was no more than 10. Unpolished and the size of a pinky nail, the stone looked more like a perfectly round zit than a precious jewel, but I liked the object’s symbolism: Like every lasting relationship, it would take time and diligence to reveal its hidden radiance.

But the morning the Supreme Court sounded its verdict in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, everything changed—just as everything changed those many months before.

The ruling was neither the slam dunk conservatives in favor of so-called “religious freedom” had been hoping for nor the final blow LGBTQ people hoped would end the conversation. To mix sports metaphors, legal eagles claimed it was a punt. In a 7-2 ruling, the Supreme Court found that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had treated Lakewood, CO baker Jack Phillips unfairly in weighing the 2012 case. They argued that the civil rights body’s verdict displayed unconstitutional bias against people of religious conviction.

Thus, the decision didn’t determine whether Phillips, who denied service to gay couple Jack Mullins and Charlie Craig on the basis of their sexual orientation, had the right to do so. That would be determined by future court rulings.

While the ruling was deemed “narrow” by advocacy groups like the American Civil Liberties Union, its interpretation has been divided. The Arizona Court of Appeals applied Masterpiece to uphold a nondiscrimination ordinance in Phoenix, but Liberty Counsel, the far-right law firm that defended Rowan County, KY clerk Kim Davis in court, viewed it as a mandate to begin chipping away at protections for LGBTQ people across the United States.

In truth, that work has already begun. Last December, the Supreme Court declined to take up Pidgeon v. Turner, in which plaintiffs argue that the same-sex spouses of Houston city employees are not entitled to partner benefits. That case, which was originally filed prior to Obergefell v. Hodges, has now been remanded to Texas lower courts for further consideration.

In the wake of the Masterpiece ruling, news outlets reported an East Tennessee hardware store—Amyx Hardware & Roofing Supplies in Grainger County—put back up a “no gays allowed” sign originally hung following the legalization of same-sex marriage. But in truth, that sign has been up all three years.

Meanwhile, a South Dakota lawmaker recently argued that businesses should have the right to deny service to other marginalized groups—like people of color.

When LGBTQ advocates won the right of all couples to be married in each of the 50 states following a decades-long struggle for equality, they successfully argued that all love is equal. The commitment between Edie Windsor and Thea Spyer, whose 44-year relationship formed the legal challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act, is no different than the devotion shared by heterosexual partners. The only thing that separates the two is stigma. When Windsor proposed in 1967, Spyer wore a diamond pin in fear an engagement ring would out them. Coworkers at IBM thought Windsor was dating “Willy Spyer,” a fictional brother the two invented to prevent from being fired.

Even today, LGBTQ people can be terminated from their jobs in 28 states if they are discovered to be queer or transgender. After first-grade teacher Jocelyn Morfii posted photos of she and her wife getting married on Facebook, the Miami Catholic school where she taught sacked her within the week. The school’s principal called Morfii’s termination a “difficult and necessary decision.”

While advocates have eloquently argued for the dignity of queer love, what society has yet to catch up to is that our rights as married people deserve the same consideration.

When I got married two years ago, I did it because I can’t imagine spending my life with anyone else but the incredibly kind, patient man who put together an unnecessarily elaborate dresser from IKEA for me just days after we met. He was my first date when I moved to New York City from Chicago in 2014. I hadn’t planned on dating anyone, but one day, a dog I was fostering from a rescue shelter had a violent seizure, and I didn’t know who else to call to help take her to the animal hospital. He was there, he kept being there, and that constancy grew into love.

Just as much of a consideration in that decision, though, were the 1,138 benefits that flow from marriage—which include rights of inheritance, tax deductions, insurance coverage, and rights of visitation in hospitals and emergency waiting rooms.

The day that my mother had a brain aneurysm, her partner of eight years wasn’t allowed in the room when her doctors forced a feeding tube down her throat. Her brain was bleeding internally, so she fought the medical professionals who were trying to help her as she lashed out in pain—like a hunted animal thrashing violently to prevent its capture. Because she and her partner weren’t married, he couldn’t be there to help calm her. So the doctors on duty placed her into a medically induced coma in order to insert the tube. She would never wake up from that coma.

The burden of the choice he never got to make has weighed heavy on him since: What if he had been present to say “no?” Would she still be alive?

These are decisions no one should ever have to make, and yet too often, the friends and family who know us best will be forced to act on our behalf: as powers of attorney, caregivers, and voices when we cannot speak for ourselves in times of emergency. Having that person is especially important for LGBTQ people, who experience disproportionate discrimination in nearly all facets of public life. When Tyra Hunter, a transgender woman who lived in Washington, D.C., was injured in a car accident in 1995, the medics refused her care after they sliced open her pants and discovered her anatomy wasn’t what they expected. She died in the hospital.

The morning that the Masterpiece ruling came down, I knew we were in for a long fight 23 years after her death. I knew that even if my husband and I did everything we could to ensure I would have someone there to advocate for me, we could take nothing for granted.

That day, I called my husband, my grandmother, and other members of my family and told them that if something ever happens to me, don’t send me to a religious hospital. Earlier this year, the Trump administration reshuffled the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to create a new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division, an office devoted to allowing people of faith to refuse service to LGBTQ people. Considering that one in six hospital beds in the U.S. are housed at Catholic medical centers, that decision could mean the difference between life and death in far too many cases: cases like Tyra Hunter’s and, in the wrong circumstances, maybe even cases like mine.

No matter what the religious right has argued in court, this discussion is not about cakes or flowers. It’s not even about love, really. It’s about the right of all of us to be treated equally under the law. It’s about whether I have the right to live and whether my legally wedded husband has the right to make that choice.

My mother’s death was the worst moment of my life. When I got the call that morning she was in a coma, all I could think about was the things I never got to tell her. My mother was a career survivor—of sexual assault, domestic violence, and cheating husbands—who raised me in a one-bedroom trailer with a half-collapsed roof. In order to make separate rooms for us, she had to bisect what was originally intended to be a living room using particle board. She gave everything to raise me, and all I wanted was the chance to acknowledge her sacrifice. I wanted to say, “I see you.”

The only thing I can imagine that’s worse than that is not getting to be in the room at all when it happened. I got to be the one sitting next to her, tightly gripping her hand in an unspoken pact. That’s the same thing we all deserve.

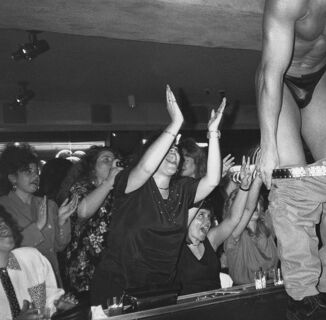

Illustration by Bronwyn Lundberg

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox