Even in an age when sharing mundane details online is standard, it’s easier than ever to control the way others see usuntil, as people often say on social media, someone’s been “exposed.” Welcome to Exposed, a monthly column where author and activist Chris Stedman invites you to get a little more vulnerable.

Chris is the author of Faitheist and his essays and columns have appeared in Salon, The Guardian, CNN, MSNBC, The Advocate, The Rumpus, and The Washington Post. After spending the better part of his 20s working at Harvard and Yale, he now lives in Minnesota, where he is working as a community organizer, writing a book on messiness and vulnerability, and messily tweeting at @ChrisDStedman.

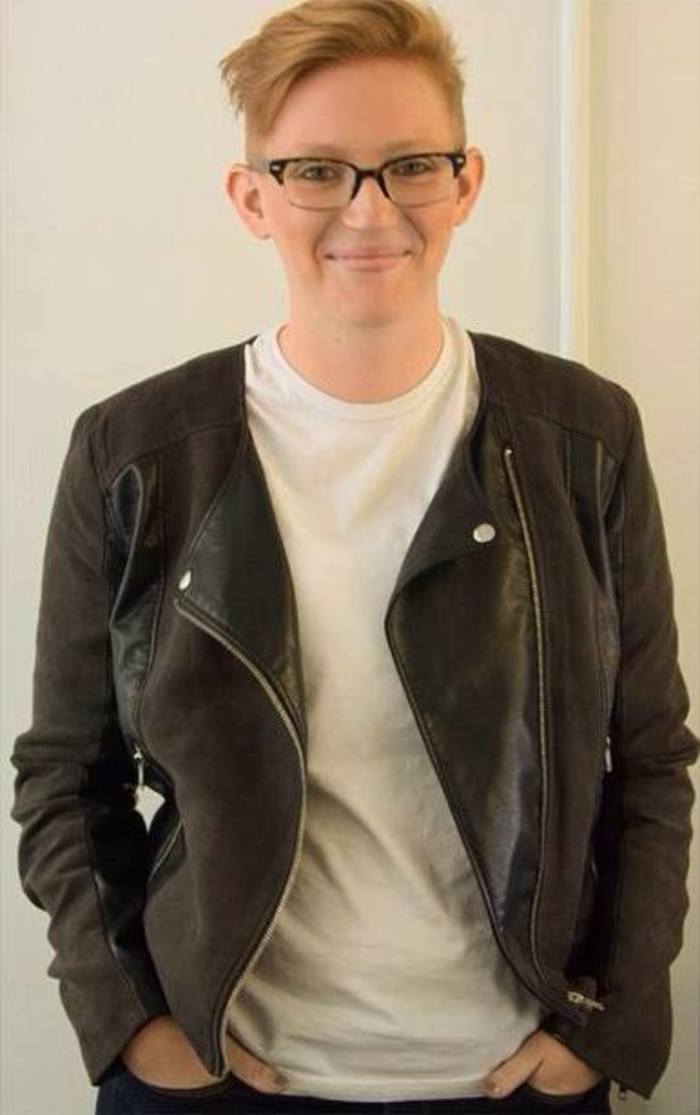

Want to get exposed? Email Chris at [email protected] with a short description of a time when you felt truly vulnerablein either a positive or a painful way (or both). This month Dean, a genderqueer school teacher in New York City, shared their story with Chris over a spotty Skype connection.

“Is this an April Fools’ joke?”

Sitting at a desk in the dead center of the office suite, Dean read these words and froze. This question was the first response to an email sent out by Human Resources just minutes earlier, one informing employees to use they/them/their pronouns when addressing Dean. The message, which Dean had worked on for weeks, also instructed their coworkers to call them “Dean” instead of by their birth name.

Dean was widely regarded among coworkers and friends as sarcastic but never mean, the one person you could always count on to come up with a clever retort to anything within seconds. But in that moment, Dean was speechless.

Their neck swelled, pressing against a crisp black dress shirt buttoned all the way to the top. This crude response on the computer screen, all of six words, was a confirmation of Dean’s worst fears: “Others won’t understand or respect my true self, so if I have to share it, I need to seem invincible.”

Dean was one of only a handful of employees in the 70-person office who were not cisgender straight men. Sitting upright at their desk situated directly in front of the front entrance, Dean suddenly felt like every last one of their coworkers was looking right at them.

After months of nurturing this piece of themselves privately, letting it grow undisturbed in a protective cocoon, this information was suddenly available for public consumption. People now could feel entitled to ask inappropriate questions, volunteer unsolicited opinions, or evenas the first respondent to the email already hadturn it into a joke.

For Dean, publicly identifying as genderqueer was a process. They started by cutting off 11 inches of hair, wearing a binder, and shopping for clothes in the “men’s section.” Then they began telling supportive friends that they were changing their pronouns and wanted to be called by a different name. But as the disconnect between their personal and professional lives felt increasingly like a sinkhole that might swallow them up, they reached a point where they needed to share this information more broadlyto stop feeling like they were literally two different people with two different names and gender identities.

Change and personal growth usually happen gradually. First, like Dean, we start to notice shifts within ourselves. Glimpses of recognition begin to bubble up, and sometimes, if we’re paying attention, they coalesce enough that we’re forced to recognize we may no longer be the person we once thought we were. Sharing this new understanding of ourselves with others is often a gradual process, too.

But in a world of live-tweeting and Instagram stories, we can’t always carefully unfurl complicated and difficult truths about ourselves. It can feel like we need to put out a press release whenever anything significant happens.

That means that anyone can see it, even those we don’t want to share it with.

A few weeks before the email to coworkers Dean logged onto Facebook after a night of drinking at a dive bar with their girlfriend and changed their name. It was a step they’d been yearning to take for months. Most of Dean’s coworkers weren’t friends with them on Facebookbut their mom was. Updating Facebook meant they would have to talk to their mom about it.

These giant leaps are terrifying. I’ve often hesitated to post even small things online, worried that they would be seen by my mom, a colleague, or someone I wanted to impress. From playful jokes about sex (which I’d instead text to a friend) to experiences of loss or failure, I’ve often held back online. Anything complicated, painful, or that I didn’t feel ready to answer questions about was filed away. Meaning that even as I mocked the lack of subtlety in carefully curated Instagram personalities in a group chat with friends, I, too, was presenting an edited, safer, toned down version of myself online.

We all do it. Even if we’re not posting heavily filtered photos of ourselves alongside some product we’ve never even tried, it’s so easy to create different versions of ourselves in different spaces, especially digital spaces. We’ve all tweeted and deleted, left something in our drafts for months, or posted something that only seems vulnerable, keeping the thing we really wanted to share to ourselves.

This goes much deeper than social media for many of us, especially for queer people. We were warned by a world that didn’t want us to exist that if we share too much, we could be rejected. No wonder we often only share partial versions of ourselves.

The fear of putting it all out there initially meant Dean feltlike they needed to put walls up and close themselves off from others. But moments after they received the email asking if their identity was a joke, another coworker, one who hadn’t met any openly LGBTQ people prior to joining the company, came up to Dean’s desk.

“So ‘Dean,’ huh?” he said.

“Yep,” Dean replied, bracing themselves for what was coming next.

“Okay,” he said. “Cool.” And then he walked back to his desk. Just five words, five minutes after six had hurt them, and Dean felt seen and understood.

Sometimes, when we think about sharing our full selves online, many of us only imagine the worst possible outcome. This fear can paralyze us. But the truth is that, while there will certainly be rejection and cruelty, there will also be people who welcome our complexities. Instead of having a partial version of ourselves embraced by many, we may find a smaller number who appreciate us for all that we are. Revealing ourselves more fully can reveal who should stay in our lives, and who we should let go.

A couple weeks ago many LGBTQ people, including Dean, celebrated National Coming Out Day. Established in 1988 by activist Jean O’Leary and psychologist Robert Eichberg, it’s an opportunity to honor the act many queer, transgender, and nonbinary people take of sharing our true selves with the world.

But while it can feel affirming, it’s also a day when many of us reflect on the people we lost when we came out of the closet.

The closet is a well-trodden metaphor for queer people, and for good reason. As a kid, I hid a journal in my bedroom closet that detailed my struggles with being queer. My mom eventually discovered it and confronted mebut while my first reaction to her discovering my secret was to literally hide my face in my hands and pray that I might disappear forever, this exposure was ultimately the first step in my coming-out process. But even as I got older I continued to hide things in my bedroom closet, like empty liquor bottles before I got sober or the “personal” items I didn’t want my mom to see when she would visit me as an adult.

We all hide things within ourselves, but that’s not always harmful. Closets help us organize, keep order, and contain. They hold the things we don’t need to use all the time and guard our most intimate possessions. But closets are also where we sometimes shove our mess away and try to forget about it, only to rediscover it later.

Sometimes, putting pieces of ourselves away is necessaryespecially for members of marginalized communities, like LGBTQ folks, women, people living with mental illness and addiction, and people of color. We can’t always be fully exposed. But we still shouldn’t have to feel like we’re two different people living two different livesat work, in our relationships, or onlinein order to stay safe.

This world tries to make us uncomplicated and easier to understandespecially on social media, where you’re asked to describe yourself in 140 (or 280, ugh) characters or less. But in a world where gender norms are rigidly enforced in ways both overtly violent and perniciously subtle, genderqueer, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people like Dean are leading the way, showing that we don’t have to be boxed in and small.

Today Dean works as a teacher in a school where no one knows their birth name, where no coming-out email is needed. They’ve swapped dress shirts buttoned all the way up to protect themselves from the world for more comfortable clothing, and traded closed-minded coworkers for students more curious about their dating life than their gender identity.

Like so many of us, Dean continues to come out of closets both online and in their personal life. But the closet is no longer their default. They don’t live there.

After exposing their true self to coworkers, friends, their mom, and the world, Dean feels more free to be who they are than ever before. It is a hard-won freedom like the first warm day in April, when the melting snow reveals a reborn flower pushing its way up through the dirt. And it is anything but a joke.

Photography courtesy of the subject.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox