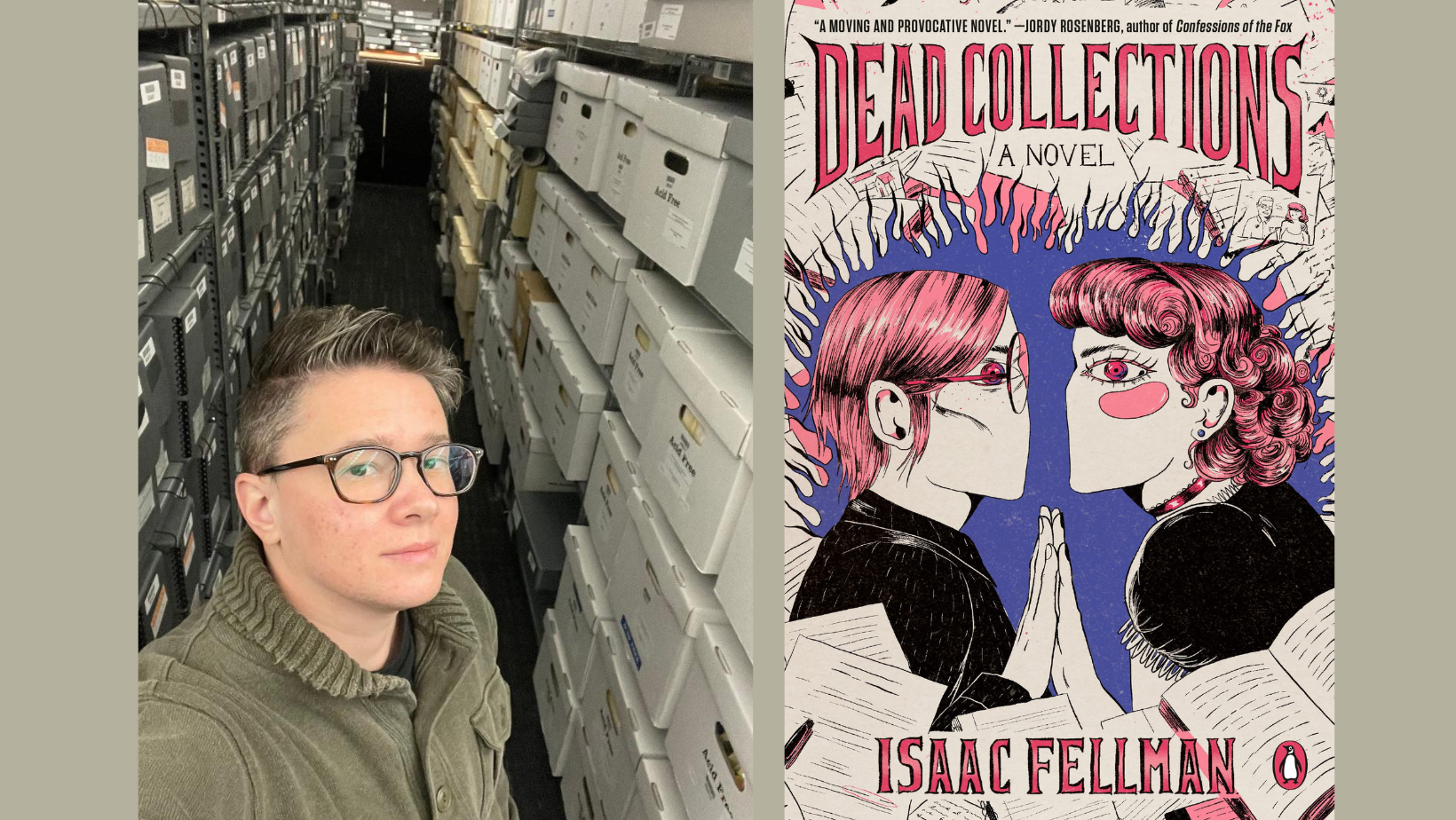

Isaac Fellman’s vampire romance novel “Dead Collections” is revelatory, refreshing, breathtaking, and magnificent. It would not be an understatement to say there are moments of pure trans holiness written into this novel. It reads like an invitation to reimagine your body and gender, and feels like a love letter to our relationship with fandom.

The story follows Sol, a trans vampire who works in an archive. In this novel, vampirism is seen and treated like a chronic illness, so Sol is living with a disability. He falls for Elsie, who brings her dead wife’s belongings into the archive because she wrote a popular sci-fi show –one that played an integral role in Sol realizing his transness. Through Sol and Elsie’s blossoming romance, he helps Elsie rethink and experiment with ideas of gender. INTO spoke to author Isaac Fellman about writing a novel that honors transness, disabled people as Romance heroes, and how we can ensure queerness is archived correctly.

Dead Collections (2022) https://t.co/0g7C17uxlT

— Isaac Fellman (@isaac_fellman) May 2, 2022

Both Sol and Elsie are in their forties, experiencing various gender, sex, and love milestones that others may have had earlier in life. Why did you want to tell this story with characters at their age?

I’ve always been interested in characters who are getting older and questioning the decisions they made when they were young. I am almost forty now, and here’s what surprised me about actually being no longer young: it’s not about questioning your decisions. On the contrary, you tend to accept what’s happened to you, because you can’t imagine being a different person. What does hit at this age is the recognition that – even if you have been through a few things and feel mature – some things still have to happen for the first time.

There are many things you’ve never done, and in those areas, you’re not yet mature, you’re not yet wise. I find that position embarrassing, and I think embarrassment is the key to storytelling. And I really do mean embarrassment, not humiliation or something intended to make the reader cringe. Although those have their uses too, they don’t encompass the same full spectrum of feeling. When we blush with embarrassment, it means we’re experiencing something unfamiliar.

In the 2010s thousands of seemingly straight women were obsessed with MLM almost exclusively. Today those same people realized they were trans or under the queer umbrella, because as it turns out, exploring queer media is an excellent/safe way to examine your own gender/sexuality

— roller skate villain (@redemptionarcs) May 6, 2022

Can you tell us about writing the moment when Elsie awkwardly assumes Sol is nonbinary? It’s somehow sweet, but also heartbreaking because Sol must clarify that he’s a man with the caveat that “I just don’t pass” and we know that because he’s a vampire his body will stay that way forever.

People like to assume one of two erroneous things about hormonal transition. One is that it doesn’t do much to change your appearance. The other is that it must change your appearance dramatically, controllably, and on a set schedule – which means that if someone doesn’t look like a cis person to you, it follows that they’ve chosen not to. Elsie’s assumption is also founded on other incorrect ideas – that nonbinary people don’t want to look like cis people; that there is a consistent way that cis people look – all of which just reflects Elsie’s lack of community, and ultimate loneliness, as a person who is nonbinary but can’t give themself permission to be.

It would not be an understatement to say there are moments of pure trans holiness written into this novel.

For Elsie at the beginning of the book, nonbinary identity is for people who are younger than Elsie, or more butch, or who have smaller chests that they can bind comfortably. It’s easy for them to put Sol on that pedestal, even at the cost of seeing him as he is. Although I’m a pretty binary trans person, I’ve certainly felt all these sorts of emotions towards trans people before I came out, and I wanted to capture that seething mixture of bitterness, envy, admiration, denigration, and various kinds of thirst that comes when you’re miserable and can’t imagine yourself any happier.

This novel, to me, feels like one majestic invitation to being trans. I loved how generous Sol is, guiding Elsie through a joyful exploration of gender expression. There’s encouraging, expansive conversation, as well as practicality —using binders, impractical office regulations, discussing deadnames, trying vibrators during sex, using a whiteboard in the morning to announce pronouns for the day. How did you balance the amount of hope and inconvenience to include in your representation of trans life?

It helps to think of it as one character’s story at a time, rather than something that has to represent all trans stories. This can be a tricky line of argument, and it’s sometimes used to abdicate an author’s responsibility to tell a story in a fresh and sensitive way, but fundamentally, it’s also true: you’re not telling the story of trans people, you’re telling the story of some trans people, and that means you don’t need to decide how to keep things in cosmic balance.

You just do what every author does, which is to listen to your instincts about the shape of the story, while also questioning the reasons you may expect a story to go a certain way. Are you tending towards tragedy, for example, because you think it’s the best way to lay bare your characters, or because you think trans lives must be tragic? Good luck getting to the bottom of that kind of question, of course, but even the top layers are going to help you be a better artist.

I think embarrassment is the key to storytelling.

We need to approach trans people’s stories with a feeling of abundance. We need to assume that there will be room for other stories tomorrow. We also need publishing and the public to provide us with that abundance – to let their attention allow for multiple stories, to see that they can read our stories for pleasure rather than edification, just as we can read cis people’s stories for any reason.

Were there are specific rules or goals you set yourself in how you’d describe Sol’s body? —I’m thinking of the way his transness and vampirism coincide, and the reawakening of it with Elsie.

They had to find each other sexy in immediate, no-nonsense ways, and they needed not to judge their sexiness against some imagined standard of cis sexiness. I didn’t have any set rules about how to name their body parts and so forth, although I did remove a more commonly feminine term for a certain aspect of Sol’s junk, because a masc I know complained that mascs don’t use it. I actually do use it, but figured that was a litmus test for how a lot of mascs would respond. It wasn’t a hill I cared to die on. If you’re going to make the reader feel horrible, you’ve got to have a better reason for it.

There’s so much romance in way you wrote the couple navigating Sol’s need to stay in the dark alongside Elsie’s fear of driving at night. It felt to me like a fantasy come to life —disabled people getting the same level of romance we see for others. Was that intentional? What did you want readers to see in the many ways you present disability to them?

Yeah, absolutely intentional. An important caveat: I’m mentally ill, but not physically disabled, and I feel like my experience with disability isn’t foundational to my life. Basically, the world is designed for people with my abilities, even if it isn’t always comfortable for me. So I didn’t want to be as edgy with the disability stuff as I was with the trans stuff in “Dead Collections” – no equivalent of the “you think I’m nonbinary because I don’t pass” bit, which I sincerely think requires lived experience not to fuck up; you need to have nuanced relationships to concepts like “nonbinary” and “pass.” But I certainly was thinking about conversations I’ve had with disabled friends, especially people who do academic work in this area.

I’ve certainly felt all these sorts of emotions towards trans people before I came out, and I wanted to capture that seething mixture of bitterness, envy, admiration, denigration, and various kinds of thirst that comes when you’re miserable and can’t imagine yourself any happier.

These activists do a lot of work to teach us basic but important concepts like “it’s a lack of accommodations that make a person disabled,” “anyone can become disabled at any time,” and “it’s infantilizing to assume disabled people don’t fuck.” Disability is a radiantly normal experience, and authors owe it to themselves as artists to understand this kind of 101 stuff. If you dehumanize your characters, it literally follows that you’re not writing about people.

A little interview, in which I fail to resist the temptation to say thishttps://t.co/z61U6jkeWS pic.twitter.com/Dvnrvb8Y1D

— Isaac Fellman (@isaac_fellman) April 19, 2022

You’ve referred to Sol and Elsie’s relationship arc as one that turns horniness into something more, and about “the crushes we get because the way someone lives their life unnerves and excites us”, which feels… so important to me! Sometimes a crush is significant simply as a space that allows attraction to mean something or teach us about ourselves. Was it fun to write all the nuances of their horniness at forty, or was there a lot of overthinking about what it means for them?

Overthinking is not one of my vices as a writer. It was when I was younger, because I had untreated OCD, and I approached everything I did – the ethics as well as the aesthetics of writing – from that perspective. If someone took issue with a word choice on page one of a manuscript, I would start over again, because if they were taking issue with a word choice, it meant that the story wasn’t pulling them in. I couldn’t see the difference between a small problem (the need for a new opening scene, or a new reader) and a rupture that affected everything, especially since I was also a very instinctive writer.

Over time, I evolved and received treatment, and I learned to balance my instincts with thought. That means that I can slap some clay onto the potter’s wheel and get it moving a little too fast for comfort, and let the characters form themselves from there. Growth as an artist is all about gaining more control over our hands, while also relinquishing control over our instincts and our audience.

Have you had any responses from people that your book made them realize they’re trans, or question their own gender? I truly think if I hadn’t already had the “Ohhhh that’s what was going on with my feelings towards MLM content” realization during the pandemic, “Dead Collections” would have shown it to me. Even so, it felt like permission, and like community —knowing that fanfiction and fictional people are the beginning for many trans people.

I’ve had a couple of people tell me that my work has given them permission to explore, which is of course the highest compliment. All the same, that’s all a book can do for us – give us permission to think about something that’s already present in us.

Dead Collections by @isaac_fellman reading me for filth after spending years in social isolation having gender feelings about weird-looking fictional men pic.twitter.com/DhhRmPqzI2

— Blue Delliquanti (@bluedelliquanti) May 30, 2022

As a chronically ill person, I know the life of regular hospital visits, and I know the difference when there’s one friendly face to look for; specifically, a person who knows something more about you, or you can relate to. I was struck by the gentleness and quiet but meaningful generosity of the queer clinic worker. What’s the motivation behind including their interactions as part of Sol’s blood transfusion experience?

Sol is very self-absorbed at the beginning of the book. That’s not always a bad thing to be, and it’s not always a permanent state. There are moments in our lives when grief, or some other overwhelming emotion, makes it impossible to think about anything larger than ourselves. All the same, he is at a point when self-absorption is no longer helpful, and I wanted to show him beginning to bond with other trans people and other vampires. With Ari, the trans clinic worker, I specifically wanted to show Sol having a casual friend, making small talk, making low-stakes jokes about things he and this guy had in common. You don’t just need soul bonds to create a community; you also need small moments like this.

As a vampire, Sol can die instantly from exposure to the sun, but he also (to quote you) “lives in a world that doesn’t care to provide accommodations for his basic safety, so he lives in constant fear of an early death.” This mirrors the terrifying state of existence of both chronically ill and the disabled community, heightened because of covid, but also of course the trans community in the US right now. How did the ever-changing level of safety for marginalized people in real life affect the way you wrote the Dead Collections world?

We all deserve to be safe, and we shouldn’t have to learn to live in a world where we are less safe than others, but until the world radically changes, that is still a vital skill. Any writer exploring a marginalized person’s story has to talk about how they live with danger, while also not treating that danger as a natural phenomenon, like the rain or the tides; it comes from other people who choose to inflict it. A writer also has to think about how to describe such danger without actively inflicting it on their readers themselves. In talking at length about the ethics of writing, I certainly don’t mean to imply that I’ve always succeeded in striking these balances, only that I’m always trying.

Your work as an IRL archivist must be changing significantly as we move towards a more digital life. How do we go about preserving the lives of current activists, in a world so heavily spent online? What do you hope activists of our time are keeping, that they may hold onto in their homes for the future archives to catalogue?

If people want their stories to be archived – well, let’s begin by saying that this desire is not a given. The historian Jules Gill-Peterson has said some thoughtful things about how trans people’s absence from archives is sometimes a triumph, because it means that these lives escaped medical and legal control. Archives tend to tell the official story, written by those in power. But if you do want your materials to be archived, think about yourself, not the future.

Disability is a radiantly normal experience, and authors owe it to themselves as artists to understand this kind of 101 stuff.

Neither archival donors nor archivists can predict the ways that researchers will learn from archives, so your needs are the ones to worry about. Keep the things that tell the story that you tell yourself. If these things are digital, keep backups. If they are physical, keep them in a dark, dry place, climate-controlled in a way that keeps nearby humans comfortable, because humans and paper need similar conditions. Some of us can’t afford to live in homes that are consistent, or that are comfortable for either our papers or ourselves. Still, please be as kind to your history as you are to yourself, which is to say as kind as possible.

working through the copy edits on The Two Doctors Górski and I am sorry to say that this book is very good

— Isaac Fellman (@isaac_fellman) May 30, 2022

You’ve described your writing pre-transitioning as dissociative and disembodied, saying that before you were asking the question “If I was a person who felt at home in my life, what would I feel like?… which is part of the reason that it has gotten better since I transitioned.” It’s a long time from writing a book to its launch. How has your writing changed since?

I have written two manuscripts since “Dead Collections,” one of which is out on submission, the other of which isn’t ready yet (my upcoming novella, “The Two Doctors Górski,” was written in 2016 but overhauled in 2021.) I also wrote a novel pre-transition, “The Breath of the Sun,” which I don’t think was bad; they gave me a Lambda award for it. To be honest, although I’ve grown a lot during the writing of these two new manuscripts, it’s not really because I transitioned. It’s because enough people have told me that my work was good that I felt ready to experiment, and I also got older and more confident. Someone once told me that they could no longer tell the process of transitioning from the process of maturing, and both as a writer and a person, I feel that.

I am never not thinking about the author Samuel Steward retraining himself as a tattooist in order to spend all day inflicting pain on handsome sailors, only to find that in the end, a job is still a job. There is profundity in this

— Isaac Fellman (@isaac_fellman) April 12, 2022

Dead Collections is in part a tribute to Calvin Kasulke’s brilliant “Several People Are Typing,” and you’ve recommended the “wild gay ride” of Justin Spring’s Samuel Steward biography “The Secret Historian” on your Twitter. Are there any other queer books you’re into right now that we should be reading?

Recently, I’ve admired Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, about an Irish soldier from the 1860s whose identity encompasses aspects of both modern gay and trans experience. It really captures the ways that these desires have always existed, even though the way we codify and name them is always evolving. Alison Rumfitt’s Tell Me I’m Worthless is a harrowing British horror novel about imperialism and internalized transphobia; it will soon be released in the US. Lastly, Jackie Ess’ Darryl is a strangely lovely coming-out story about figuring out what in God’s name you’re actually coming out as.♦

Dead Collections is available in paperback, ebook, and audio. Fellman’s upcoming The Two Doctors Górski is now available for preorder.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox