In 1883, an Illinois man traveled to Wisconsin, landed on the doorstep of Frank Dubois and his wife, Gertrude, and issued a shocking accusation: Mr. Dubois was not a man at all, but a woman. His own wife, in fact, who had abandoned him and their two children. Reporters flocked to the scene, in a frenzy to expose this gender outlaw to the public. “You really insist that you are a man?” they asked Dubois. “I do; I am,” Dubois replied – then added stoutly, “As long as my wife is satisfied, it’s nobody’s business.”

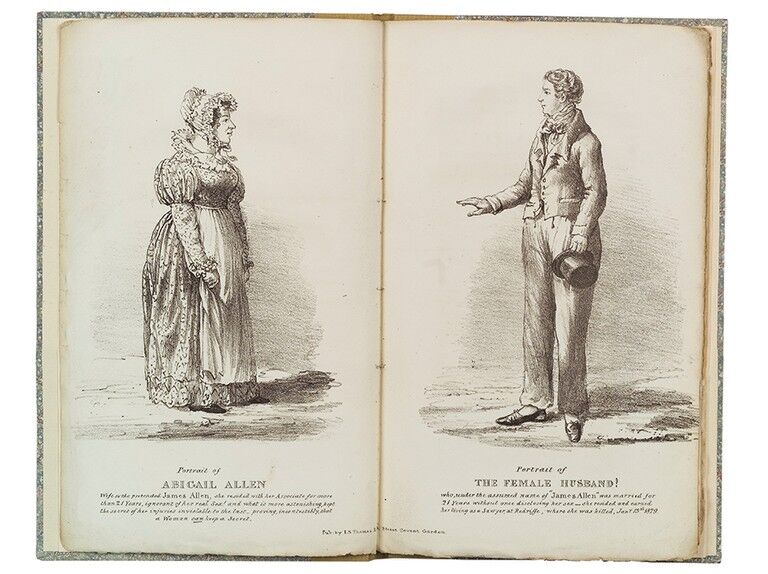

Despite this most-excellent mic drop, society made it their business anyway. Dubois’ story was reprinted in newspapers across the U.S. and spawned a flurry of public discourse on the meaning of a husband, the nature of sexual difference, and even the question of same-sex marriage. Individuals like Frank Dubois, who were assigned female at birth and at some point began living as men, were the subject of much fascination in the U.S. and U.K., and accounts of their lives appeared regularly in print beginning in the mid-18th century. These “female husbands,” as they were often described, are given fresh consideration in a recent book by Jen Manion, published by Cambridge University Press, and newly available in paperback. Female Husbands: A Trans History explores the lives of over a dozen individuals who transed gender for years or even decades, and whose defiance of the gender binary both confounded and solidified societal understanding of what it meant to be a woman or a man. Manion, an associate professor of history at Amherst College, sat down with Into More to share some of their thoughts about these female husbands, the women who married them, and what these couples can tell us about queerness across the span of time.

“The 18th and 19th centuries were full of gender nonconformity and transing in all different ways,” Manion explained. “I thought the female husbands were the most original and exciting–I decided to really focus on them, to understand the trajectory of their lives.” Manion was intrigued by the way they thwarted presumptions around gender, but also by the fundamental queerness of their marriages: “all the female husbands had queer wives.” While the wives of female husbands have traditionally been given short shrift by scholars, Manion carefully excavates their stories from the archives, too, finding names, birth years, and accounts of early life, which add dimension to these complex narratives of fidelity, identity, and betrayal.

Individuals like Frank Dubois—assigned female at birth and now living as men—were the subject of much fascination in the U.S. and U.K., and accounts of their lives appeared regularly in print beginning in the mid-18th century.

We meet, for example, James and Mary Howe, a happily married couple that ran the popular White Horse Tavern in London’s East End in the mid-1700s. When a neighbor discovered James’ secret, she began extorting the couple for payment in exchange for her silence. After Mary died, a grieving James refused to continue paying the extortion fee and outed themself so they could take the extortionists to court (Howe won.) Howe’s revelation astonished their unsuspecting neighbors, who had always regarded James Howe as a respectable man and a pillar of the community: an insight, Manion notes, into the significance of institutions like legal marriage, business transactions, and civic participation in constructing the concept of a “man.”

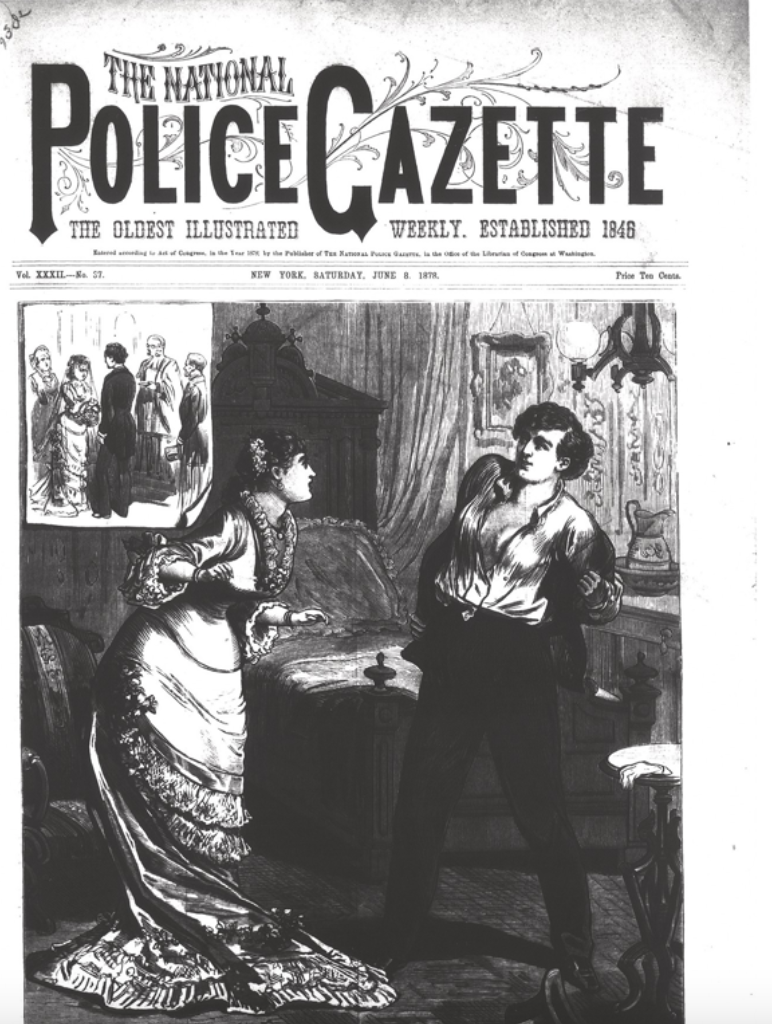

But not all female husbands had contented “female wives,” as Manion wryly refers to them: Samuel Pollard, for instance, was recorded in newspapers as being something of a rake, and their wife, Marancy Hughes, fled to her uncle’s home shortly after their 1877 marriage, accusing her new husband of abuse, ill-treatment, and–perhaps the only accusation that would have warranted intervention–artificial maleness. The National Police Gazette (with maximal shock value clearly in mind) featured an illustration of Pollard stepping out of their male attire to reveal a pillowy bosom.

A legal case attempting to pin Pollard for perjury for lying on the marriage certificate went nowhere, and Hughes left the courtroom arm-in-arm with her husband, affirming—for the moment, at least—the enduring validity of their marriage. As Manion writes, “the wife of a female husband had tremendous social and political authority in asserting their husband’s manhood.” The court, with no other legal means of punishing Pollard for their gender transgressions, was forced to let them walk free; Pollard lived the rest of their life as a man.

The hazy relationship between individuals and the state’s power over them is central to the trajectories of female husbands’ lives, both in the choices they made for themselves, and the impact their lives had in shaping social and legal constructions of gender, sex, and marriage. Manion—whose last book focused on women’s encounters with the criminal justice system in early America—deftly illustrates how people who transed gender exposed the instability of the gender binary, threatening the rigid differences of dress and behavior that Western society enforced between men and women.

Consider Charles Williams, a “female sailor” from Rhode Island, and one of very few existing accounts of Black individuals who transed gender. Williams, arrested in 1834 for stealing hogs, was imprisoned in New York City and sentenced to four months’ hard labor hauling stone. While Williams changed into their prisoner’s uniform, prison guards discovered that the prisoner was not biologically male; chaos ensued as the authorities argued over whether Williams should still have to haul stone, now that they were “revealed” as a woman. Williams’ story highlights the intersection of gender and race in the fact that authorities even considered allowing Williams to continue hard labor: Manion compares their story with that of a white female sailor, George Johnson, who despite having spent seven months on a whaling vessel performing their grueling duties perfectly well, was discovered to be female and immediately cosseted in the captain’s quarters, before being gallantly returned to shore.

The stories Manion presents in Female Husbands largely take place in the decades before the dawn of sexology, when psychologists began to pathologize sexuality and gender identity, and previously vague concepts like homosexuality and cross-dressing ossified into acts of subversion that could be prosecuted, penalized, and—later—cured. “There’s an ongoing dialogue between people who want to “trans” gender and people who don’t want to let them,” Manion explained in our interview; it was that dialogue that led to a stronger articulation of the gender binary itself.

The stories Manion presents in Female Husbands largely take place in the decades before the dawn of sexology, when psychologists began to pathologize sexuality and gender identity.

The existence of individuals like Charles Williams, Frank Dubois, and James Howe posed a grave threat to the social institutions that depended on essential, immutable gender differences to enforce the rules and regulations of an orderly political state. In responding to that threat, those same institutions effectively ratcheted up the force behind those rules, through legal inventions like prohibitions against cross-dressing, sodomy laws, and catch-all anti-vagrancy acts that allowed the state to punish racial, gender, and sexual minorities who stepped out of line. In examining the lives of people assigned female at birth who refused to yield to the rules of gender, Manion shows us how those rules themselves were created over time, and how they hardened into the rigid constructions we are now working so carefully to undo.

For all that Female Husbands does, the book’s true triumph lies in what it resists doing. Though Manion calls it a trans history, they are careful not to apply a contemporary framework of trans identity on any of the individuals whose lives they consider. “It’s possible that some, most or all of the people in my book would relate to trans identity as it’s currently defined,” Manion said. “And it’s also possible that they wouldn’t. There’s no essential truth in there for us to access.” Manion uses “they/them” pronouns for anyone in the book who transes gender, at any time, even for those who lived as men for decades. “I’m not in a position to ask all of these people how they want me to speak of them,” Manion explained. “In that respect, ‘they’ is just meant to be completely without gender. To make more space for humanity and fluctuation, with less of an emphasis on these really tiny—but very heavy—words.”

In examining the lives of people assigned female at birth who refused to yield to the rules of gender, Manion shows us how those rules themselves were created over time, and how they hardened into the rigid constructions we are now working so carefully to undo.

Rather than assume certain female husbands “were trans”—or, for that matter “were lesbians,” as earlier queer studies scholars have claimed—Manion simply considers what they did, which was to subvert gender, in myriad ways, for reasons we will never fully understand. In doing so, Manion joins a larger chorus of trans scholars, including Susan Stryker and Paisley Currah, who have pushed back against the idea of identity as the essential framework for understanding transgender narratives. Manion noted: “They were really saying, ‘in order to have robust transgender studies, we need to look at this as an analytic, as an action, as a motion, rather than simply identity.’”

By observing their lives without a contemporary lens of identity, Manion unleashes the female husbands into the limitless freedom of the past. As a scholar, they are content to know them merely by what they left behind in the record. Even if all we can know about them was the actions they took, the genders they transed: well, that is more than enough to marvel at the courage of our queer ancestors.

“You lived an unusual, unconventional life, in which you challenged lots of norms,” Manion says of these curious, unknowable, magnificent people, whose stories remind us that we have always been here. “That’s what we have in common.” In that respect, Female Husbands manages to avoid the pitfalls of our rancorous contemporary identity politics, by recounting a fascinating history of gender and sexuality that assigns no claim or authority, that simply allows the record to speak for itself.

The rest, after all, is nobody’s business.♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox