Just like so many of our private parts, gay nightlife is on the rise again!

I recently told you about a Hell’s Kitchen club called the Q, which is planning to open when we’re safely out of lockdown. And let me now advise you that promoter Daniel Nardicio has taken over the old Escuelita space on 41st Street and 9th Avenue and is looking towards an October opening.

(I also hear the Boxers owner has taken over the closed Therapy space for some new life, plus the long-running leather club the Eagle NYC has been approved to do a ground floor expansion that will accommodate a kitchen and sit-down eating section.)

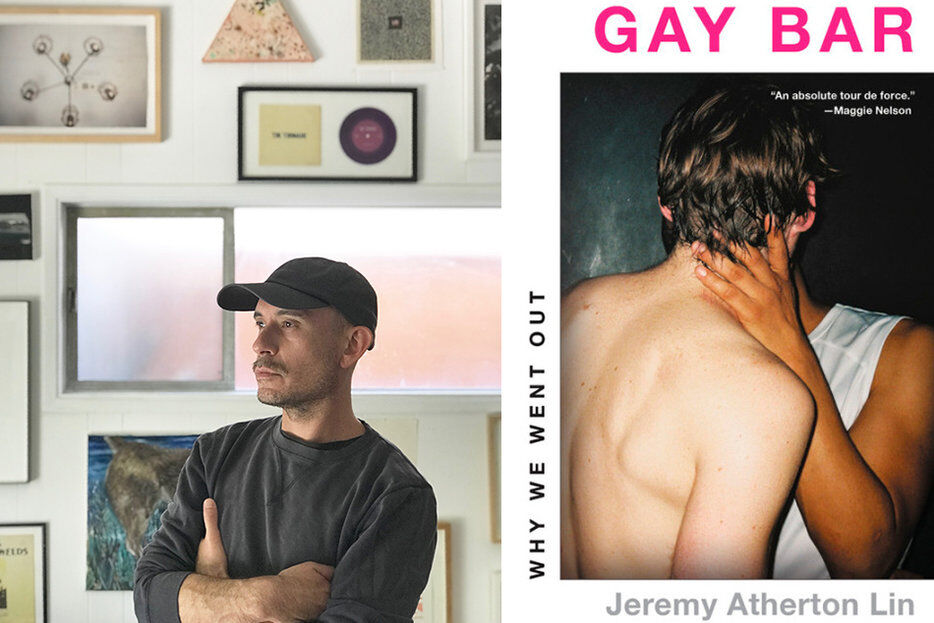

With a gay Roaring Twenties about to explode—not just in NYC, but everywhere–Jeremy Atherton Lin’s nocturnal memoir Gay Bar: Why We Went Out is as perfectly timed as a two-hour top-shelf Happy Hour.

The New York Times rave called the book “beautiful, lyrical…Atherton has a five-octave, Mariah Carey-esque range for discussing gay sex.”

This is the first book for the author–an essayist/editor—and each chapter is set in a particular bar, whether it be in London, L.A., or San Francisco. I asked Atherton some questions about the art of gay-barring and ended up hangover-free.

Hi, Jeremy. Congratulations on your book! Has the possibility of sex traditionally been the number one motivation for going to a gay bar?

I’d like to think so. I know some people are mad at me for writing from that angle–like they’d rather I’d written about searching for an alternative family, not a hot daddy. But the sex was an important motivation, not just for going to bars, but writing the book. For me, though, the sexy stuff took some time, because when I first went out — and I was taken out, you know, identified and taken along — it was more to see and be seen. This was the ’90s and a lot of us were terrified of disease. So you put it exactly right — the possibility of sex, if not actually having any. And then up through writing the book, up to the pandemic, I continued to go out for the frisson, for the feeling there could be trouble in store.

I’d like to think so. I know some people are mad at me for writing from that angle–like they’d rather I’d written about searching for an alternative family, not a hot daddy. But the sex was an important motivation, not just for going to bars, but writing the book. For me, though, the sexy stuff took some time, because when I first went out — and I was taken out, you know, identified and taken along — it was more to see and be seen. This was the ’90s and a lot of us were terrified of disease. So you put it exactly right — the possibility of sex, if not actually having any. And then up through writing the book, up to the pandemic, I continued to go out for the frisson, for the feeling there could be trouble in store.

Today, with everyone looking at Grindr on their phones, is the sexual urgency at bars completely gone?

I’m pretty “meh” about dick pics. I want to be surprised. That’s not about being a size queen, I’m talking about the tease. About seduction rather than vetting. And humor — and changing your mind about somebody. Online, we’re so self-contained. I went out to be led astray. I have a feeling that the urge for spontaneity will kick back in now that we’ve had nothing but screens.

When we fully come out of lockdown, do you predict a wild sense of abandon in gay nightlife?

Maybe. I think for the young, that’s a possibility. I’m old enough that the thought of being cheek by jowl is kind of terrifying. One thing my book addresses is how nightlife took a while to recover from the height of the AIDS crisis; how that slick, contagion-free aesthetic took over by the ’90s. Smooth bartenders, smooth bar fixtures, everything low-risk and wipe-clean. Of course, there was rave, and scuzzy rock-and-roll queer nights started happening in New York, as you know. So there’ll be that kind of stuff — the roving, illicit, peripheral parties. But I’m never one to cancel the mainstream spot for the basic gays. And those kinds of bars, the ones able to reopen in the first place, may face challenges in getting everything right, to allow for a sense of abandon and bonhomie, and make it feel effortless. Then again, maybe I’m just being cautious and everyone else is going to pile in.

Many gay bars now have nights where guys congregate to watch RuPaul’s Drag Race on a big screen. Is it weird that so much of gay nightlife has basically turned into communal TV watching?

I know, totally. I was doing that myself. To my shame — to not be focusing on local talent and site-specific artistry. But you know, I found it reassuring to be in a room full of gays who cackle at the same things— to be reminded that we as a people still get camp. I’m a bit sentimental about that resonance, this thing of interpreting pop culture for ourselves. That bond over spectating together, it’s a loose and caustic connection that I really do appreciate, as opposed to any far-reaching notion of community.

Do other countries do gay bars better than the U.S.?

I don’t think so. Berlin is fun, I get it, and Amsterdam. They’re raunchier, probably. And I’d love to hang out in Mexico City and in South Africa. One of the main differences in UK bars is that the drag queens tend to sing rather than lip-sync. It’s old school, working-class, vaudevillian. But you know, I am very attached to a good old American beer bust.

With modern gays finding other ways to connect [Internet, apps, etc.] than my generation did, are gay bars less important?

Probably, honestly — to them, anyway. I mean, I’m sure there are new modern gays who never used a fake ID to get into a gay bar and still have never been to one past their 21st birthday. I’m sure they’re fluid and queerer than gay, and all kinds of new positive, lovely things. But that more antiquated gay culture — in its archness, its facades, its reliance on not just sex but sensibility, on language and pastiche — I continue to appreciate its allure and would like to think it has repositories around the world. Gay, despite its problems, has given the world a lot.

We deserve a place to drink.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox