The Barbie movie has been a long time coming. And now we’re finally getting the star-studded, Greta-Gerwig-directed, feminist vision we deserve. And “we,” of course, mean “the gays.” There’s no question that hot pink femmes with Malibu dream homes and sportscars don’t exactly feel like the product of a straight, hetero imagination. And that’s very much on purpose.

Talks of a live-action Barbie movie have been floating around since 2009: Initially, the project was spearheaded by Dreamgirls producer Laurence Mark, later to be scrapped and revived by Sony with a script by Diablo Cody. By 2016, Amy Schumer was set to star as a doll kicked out of Barbieland for “not being perfect” enough. That project fell through, and years later, the pink behemoth that is Barbie has finally resurfaced.

“Barbie is a little like Dolly Parton,” Trixie Mattel tells INTO, referring to the gay icon status of a star who doesn’t have to be outwardly pro-gay for queer fans to cling to her (but, of course, Dolly is a true ally).

Related:

Barbie Feels the Cold Approach of Death in the New Barbie Trailer

So far, this looks like a movie that knows how absurd it is.

What’s Behind Barbie’s Queer Coding?

“Barbie was invented first,” Greta Gerwig recently explained in an interview for Vogue. “Ken was invented after Barbie to burnish Barbie’s position in our eyes and in the world. That kind of creation myth is the opposite of the creation myth in Genesis.”

No wonder the gays love Barbie so much: she’s the plastic personification of the famous “women carrying f*ggots” meme. Before it was okay to be openly gay, before it was okay to be a single, independent woman, it was more than okay to look up to and identify with Barbie, regardless of your gender.

Barbie and her boyfriend, Ken, have always been a bit fruity. As Gerwig’s film highlights, Barbie was a new innovation in toys that allowed girls to engage in a more subversive approach to womanhood. Instead of the usual baby dolls or nurture-centric toys, Barbie was a full-grown woman, had jobs, drove (something only about half of the adult female population did in the 50s), and wore a permanent bitchy expression. In essence, she — much like M3GAN — served c*nt. And in the 1950s, that alone was subversive.

But there was more: Barbie didn’t just have a job; she had a sense of self. It wasn’t until 1961 — two years after the doll’s creation — that Ken even came on the scene.

Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Rina Sawayama, Dua Lipa, Robyn, Kylie Minogue, Nicki Minaj, Megan Thee Stallion, Chloe x Halle, BLACKPINK, and literally every other pop girl releasing new music during the pandemic https://t.co/N51gT8TOSI

— Sam Stryker (@sbstryker) August 5, 2020

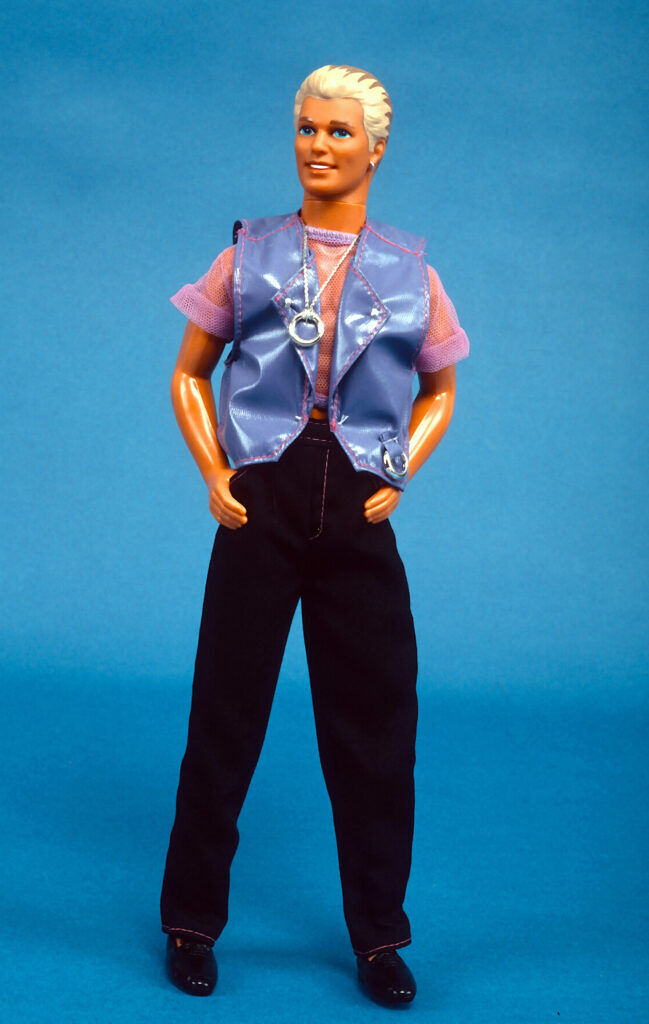

And as for Ken, Toy Story 3 introduces Barbie’s beau (Michael Keaton) as a queer-coded (potentially messy bisexual) man with a charming flair and a vibrant ascot. He’s still madly in love with Barbie (The Little Mermaid’s Jodi Benson) and isn’t far removed from how he’s appeared since inception. According to Barbie’s Queer Accessories author Erica Rand, Earring Magic Ken (a major collector’s item introduced by Mattel in 1993) might even have served as an influence for Ken’s Toy Story 3 depiction. As Rand tells INTO, Earring Magic Ken walked so Keaton’s Ken could run.

“I think their idea was just to have Ken be more like a cool guy,” Rand, a professor of art and visual culture and gender and sexuality studies at Bates College, tells INTO. “But it turned out to really look like a kind of gay club Ken.”

A quick glance at the doll confirms that he looks like a friend of Dorothy with a resemblance that may have been inspired by Ken Robert Handler, the gay son of Mattel Founders Elliott and Ruth Handler, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994.

To top it off, the 90s doll wore a c*ck ring necklace, according to Rand.

“There was a theory that some designer had a queer uncle or something [and] they didn’t understand what [a c*ck ring] was,” Rand suggests as to how Earring Magic Ken got to be so gay. “I feel like even if that was true, somewhere along the line in the design chain, somebody knew better and chose not to say something.”

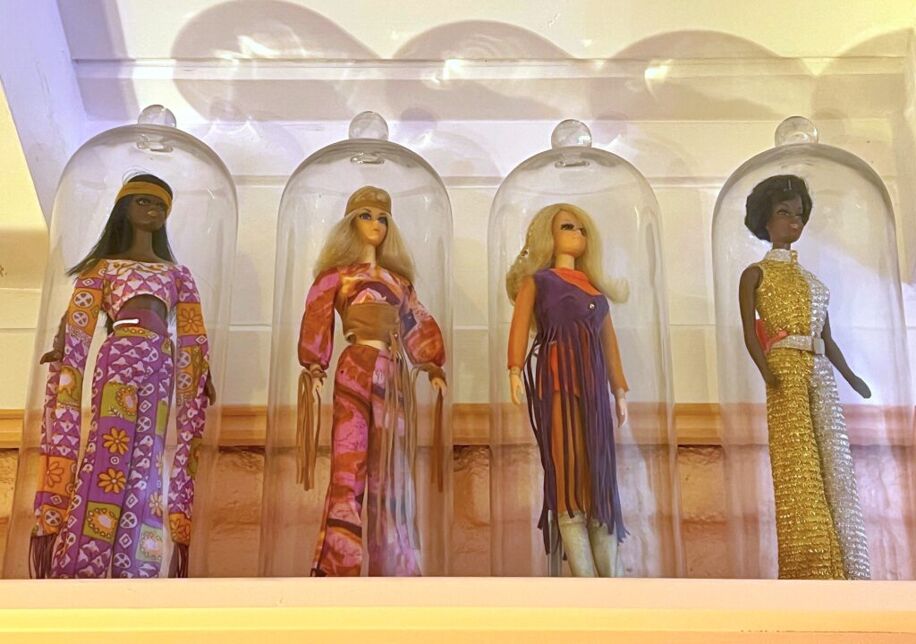

Barbie and Ken were meant to represent an ideal (and unattainable) body image: that meant long legs, a perfectly-arched foot, a six-pack, and white skin. In a country where white supremacy has everything to do with ideas about “perfect” physicality. And while efforts to diversify Barbie have come a long way, the first Black Barbie, Christie, didn’t appear until more than 20 years after her pale-skinned predecessor.

As Elektra Abundance (Dominique Jackson) explains in Season 2 of Pose, Barbie got to be every kind of person, from stewardess to CEO, before she got to be Black. “And even then,” she notes, “she still had a white girl’s body.”

Rand points out that Ken specifically is the “white ideal man” and that — partly due to the AIDS crisis ushering in a new orthorexic ideal for gay men — it’s “easy to queer [Ken]” due to him being a “beautiful looking white guy with some muscles and a very bland face,” Rand says.

Did Mattel lean into Ken’s queer icon status? If we know anything about the brand (and product marketing in general), we know that money talks, and gay money often speaks loudest of all when it comes to doll content. Whether Ken, Barbie, Chucky, or more recent doll icons like M3GAN were made with us in mind, they quickly came to reflect us: they were, and remain, the perfect metaphor for a chaotic refusal of heterosexuality and its stifling value systems.

2023: The Year of the Doll?

Speaking of ultra-femme dolls with perfect hair and a job to do, M3GAN seemed to tap into the darker side of America’s obsession with female plastic perfection when the film was released in January 2023.

On paper, having a robot doll body roll to Taylor Swift’s “It’s Nice to Have a Friend” before murdering someone seems like a concept straight out of an AI generator.

But M3GAN delivered just that from its first trailer, which debuted last October, and spawned a frenzy of new fans and internet memes that launched the film into the queer zeitgeist months before its release.

Fans edited the dance with an array of queer-friendly anthems as backtracks, including Megan Thee Stallion’s “Body” and Beyoncé’s “Cuff It.” And when the film premiered, a wacky promotional stint with human “dolls” dressed as M3GAN embodied both the uncanny valley horror of the doll along with the heinous hilarity that spawned such a fervent following.

Related:

Nicki Minaj and Ice Spice Are Bringing ‘Barbie Girl’ to the ‘Barbie World’

“Hot Barbie Summer” starts now.

Like Chucky before her, M3GAN brought a certain subversive mindset into the presumably straight American home. She was the outsourced mother from hell, intent not only on taking her babysitting job seriously but doing it better than any birth mother could. And while the film’s creators came up with meaningful reasons why queer audiences clung to this new film — like the concept of found family and belonging — others were blunt in why M3GAN was a queer icon. “I thought we liked her bc she serves c*nt,” viral content creator and queer/nonbinary commentator Matt Bernstein tweeted in response to her remarks.

M3GAN is classic camp: a theatrical, stylized version of that eerie but sacred object of feminity: the doll. The AI doll is also, simply put, hilarious. And while the movie’s deeper meaning could resonate with some queer audience members, one of the reasons they bought tickets in the first place may be that her flare would slay in a RuPaul’s Drag Race lip-sync, pun intended.

But there’s more M3GAN packaging to unwrap: the film takes something familiar from childhood, and makes it newly sophisticated, violent, and funny in the same way that American Girl doll memes have transformed into a potent kind of online discourse — threads that highlight the “need” for an American Girl doll who wrote her thesis on silly bandz as a classist social structure or a doll who was on stan twitter in 2013.

The American Girl empire — an extended doll universe that many of us grew up with without question — takes on different meanings with adult awareness and queer adjacency. Online posts about how we need an American Girl doll who was on Omegle at 12 or sh*tposts about current events quickly went from funny to political. A fake American Girl account (verified briefly thanks to the Twitter Blue debacle) even tweeted, “Felicity owned slaves,” referencing one of the brand’s historical characters and a descendant of plantation owners. While some have created memes for social commentary, others simply love a good gag and dolls just as much, creating a strong foundation for M3GAN.

Who knows what kind of self-reflective art M3GAN, in turn, will inspire 20 years from now? If she’s anything Barbie, she’s destined for a long cultural life in the queer canon.

Dreaming of Dolls and Freedom

Through research for her 1995 book, Barbie’s Queer Accessories, Rand discovered various sectors of the LGBTQ+ community related to Barbie differently and create their own stories for her and her friends. She mentioned how “a lot of dykes” or butch lesbians rejected the doll and her feminine charm. Or they might have preferred Ken. Rand says that Barbie allowed people to play with gender expression while not necessarily exploring their own sexuality. Although she also heard stories from future lesbians making their Barbie have sex with her best friend, Midge, who was introduced in 1963.

Barbies were not just mere playthings; tools that allowed all kinds of kids, but especially queer ones, to play out gender fantasies, create same-sex relationships, or dress in fabulous outfits when those things were otherwise discouraged. Author and comedian Justin Elizabeth Sayre tells INTO that dolls are “a little projection of dreams” for many young queer people who might live in a world where their authentic self is stifled and they’re encouraged to hide.

Similarly, Trixie says that the draw of Barbies “comes down to freedom” for gay boys or anyone who didn’t neatly fit into a hyper-masc label as a kid. “When you’re young and you’re gay, and you’re mostly male, you’re supposed to be XYZ. And when you aren’t those things, you’re like, ‘If there are these big parts of myself that I have to minimize, here’s this little outlet to play all those realities out.’ ”

To Rand, it makes sense why queer audiences clung to the ridiculousness of M3GAN, similar to why we see gay context everywhere or discover joy when our lives might not be as such.

“Queer, trans, and nonbinary people, among other marginalized people, have often had to repurpose popular culture to serve us,” Rand says. And despite Barbie’s commodification, we can still make Barbie act, say, and be whoever we want her to be.

Trixie recalls how, as a youngster, the idea of being able to manipulate Barbie in her own hands and have no restrictions was liberating. And as adults, we can break free of those constraints and be someone like Barbie, who, according to Trixie, was “never self-important or better than anyone else. She’s the absolute line between relatability and just-out-of-reach perfection.”

Trixie isn’t alone: millions of vulnerable queer kids have used dolls to play out and explore the forbidden fears, questions, and insecurities they have about queer adulthood in the safe realm of the playspace. The realm of play implies that nothing can be a true mistake: there’s always the ability to stop the game and start over again.

When Sayre, the author of Husky and From Gay to Z: A Queer Compendium, believes “queer culture is transformative.” If Barbie was made to reflect an impossibly perfect hetero world, it didn’t take much to subvert that image. It’s what queer folks have been doing since the dawn of time: Lana Turner and Judy Garland never played gay characters, but when we saw them onscreen, their queer appeal was unmistakable.

We’re all born naked, and the rest is Barbie.

Trixie Mattel

“Because we’re taking things, and we’re turning them on their head,” Sayre explains. “We’re transforming them into something new.”

As for Barbie’s future, Sayre agrees that Gerwig’s Barbie “has to be” camp. “They’re not just representing the world,” they say about queer creators. “They’re asking you to look at the world in a different way.”

At a time when queer and trans children are under attack, Barbies and other dolls can be essential. Not just for playing but for creating a safe space where the world can become what we want and need it to be. The power is in our hands, and no one can stop us from creating our own dream world.

“We’re all born naked,” Trixie says, “and the rest is Barbie.”♦

Additional contribution by Mathew Rodriguez.

Don't forget to share:

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox