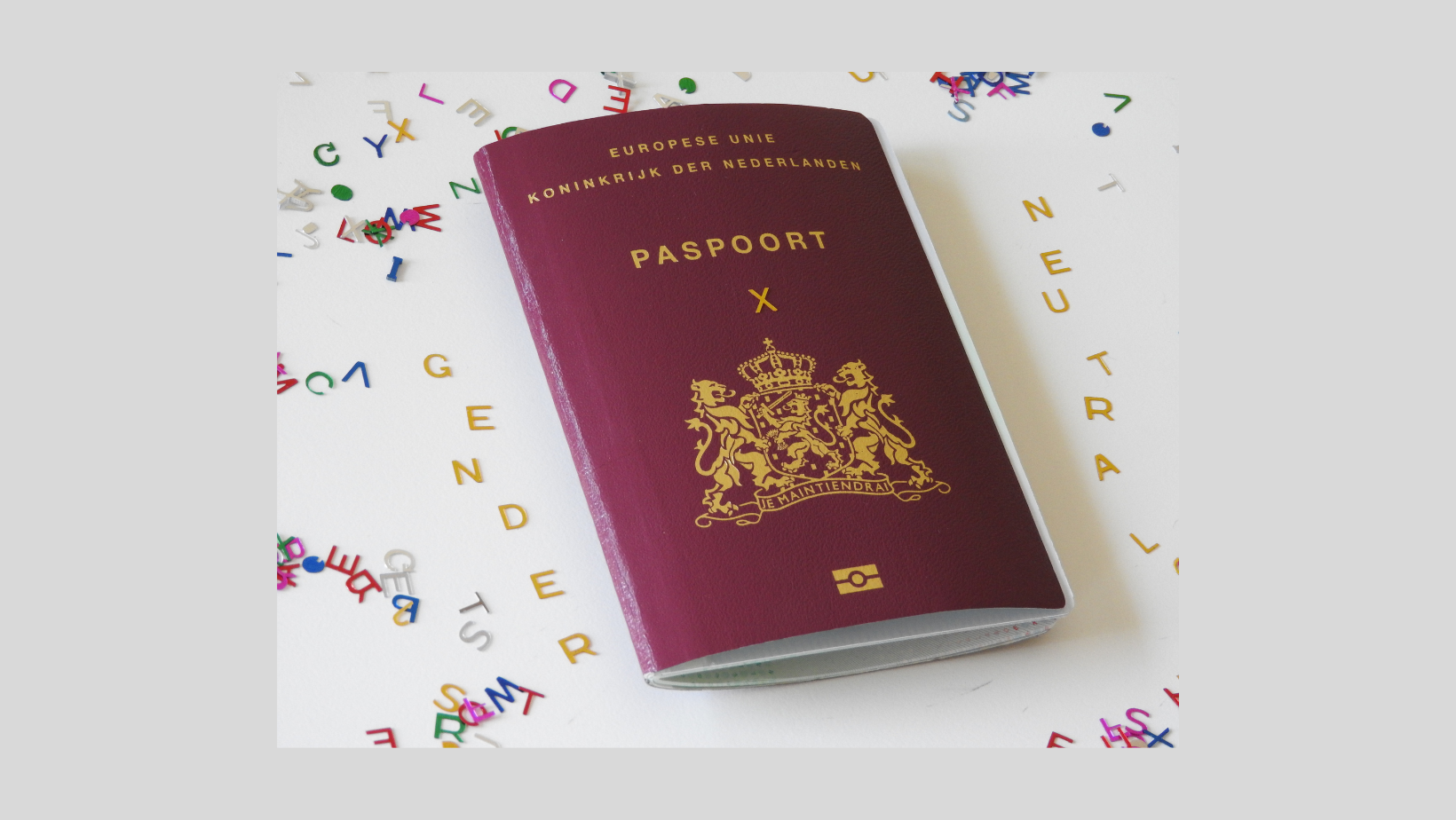

For most, it’s a given that gender is included on most identification. Whether it’s a passport, a driver’s license, or something else, a small section for gender with a binary “M” or “F” will be there. When filling out forms for most places, your gender is one of the first things that’s asked. And while more places are getting better about including diverse options, in a lot of ID situations it’s still just “male” or “female.” This poses obvious problems for nonbinary people, and means that trans people are given an extra step to avoiding misgendering as they go through lengthy processes to get documents changed. For nonbinary people, a slow but consistent push is being made to have an option for gender to be listed as “X” instead of “M” or “F.” While this is an improvement, it is not a perfect solution.

With the ubiquity of gender on passports and other IDs, it might be easy to assume that a gender designation is an important and necessary part of the ID and that this has always been that way. However, the history of passports and the gender listed on them is more complicated (and more recent) than you might assume. To understand why gender—whether using “X” or not—is a problem on a passport and what a better solution would be, it’s important to understand how we got here.

Note: much of the following information is specifically in regards to the history of passports in the United States, but the issues around passports and this specific country exemplifies the issues around other forms of ID and countries nonetheless.

The history of passports and the gender listed on them is more complicated (and more recent) than you might assume.

The basic concept of a passport can be tracked back to at least roughly 450 BC, when the Hebrew Bible included a reference to a letter from a king requesting that someone be given safe passage. Passports that are more similar to the ones that we use today came much later, but still centuries before now. In England, King Henry V supposedly created the idea of a document that was designed to prove his subjects’ identities while they were in foreign lands. Crucially, however, none of these documents included any indication of gender.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

While it might seem like this comes down to a lack of need in the historical context for women to have passports, the introduction of passports in the United States demonstrated that that was not the only reason. The United States has had passports since before the Declaration of Independence was signed, but didn’t have a fully standardized system until the late 1800s. At this point, unmarried women were able to have passports and these passports did not include their gender. (It wasn’t until 1923 that a married woman first was able to get a passport in her own name, including her maiden name, as before this she was simply listed as “and wife” on her husband’s passport.)

Despite women and men—both married and unmarried—having passports in the United States since the 1920s, it was still decades before gender was ever included on these identity documents. It was not until 1977 that gender first appeared on US passports: far from a long-standing historical tradition, the practice only came into effect less than 50 years ago. After convening a panel of experts to standardize travel documents internationally, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) declared that one of the details needed on these IDs was “the bearer’s sex.” The reason given for this, strangely, was the growing trend in early-1970s fashion for androgynous hairstyles and clothes that made it harder to identify a traveler’s gender as their photograph was no longer being seen as a clear indication. The new gender markers were of course defined by birth certificates. In 1992, a policy regarding trans people came into place that required them to have extensive surgery, including sterilization, to be able to change their gender marker, a policy that wasn’t reversed until 2010 and never gave any room for nonbinary genders.

While it might seem like this comes down to a lack of need in the historical context for women to have passports, the introduction of passports in the United States demonstrated that that was not the only reason.

While this background explains (within the confines of a society eager to know which binary box they can put a person into) why gender is listed upon US passports, it fails to explain why the gender of a traveler is of any import. Although some arguments could be made for holding demographic data about travelers, etc. none of these arguments are particularly compelling, as demonstrated in part of a 2018 lawsuit. Dana Zzyym filed to have their nonbinary identity recognized on their passport after a U.S. District Court filed a ruling ordering the State Department to give them a passport with an “X” in the gender field.

In the ruling, U.S. District Judge R. Brook Jackson noted that the reason provided by the State Department for not giving Dana Zzyym a nonbinary passport previously was a memo based on the ICAO decision from the 1970s surrounding androgynous fashion. Judge Jackson noted that this made little sense as the ICAO has changed its standards since the 1970s, and the original decision failed to include any reasoning for why the gender identity of a person needed to be known in any regard.

It took until October 2021 for Dana Zzyym to receive a passport with the “X” gender marker, but they did finally receive it, as the State Department was unable to provide a reason why they should not.

Adding the “X” gender markers to passports is a huge step forward in recognition for the nonbinary and intersex communities. Not having to identify yourself as male or female avoids some issues of misgendering, however, it still poses its own problems. The “X” identifier is not a true statement of gender, but rather the absence of a full acknowledgment. To fully encapsulate the possible gender identities of ID holders, documents would need to have more options than is truly feasible for this type of document to have. The “X” simply marks the holder as different and “other,” and might pose problems for the bearer in some more conservative countries. Additionally, while it might sound paranoid to say, requesting the “X” gender marker on a government-issued ID will mean that future administrations have a convenient list of people who identify as outside of binary gender norms if they ever wanted to persecute a marginalized portion of the population.

Not having to identify yourself as male or female avoids some issues of misgendering, however, it still poses its own problems.

This concern isn’t simply a hypothetical, but comes with historical precedent as census data was used by the government in the establishment of the Japanese-American internment camps during World War II. Other members of the trans and nonbinary community have already spoken out about not wanting an “X” to mark their gender. Writing for the ACLU in February 2021, Spencer Garcia talked about how they preferred the option to have no gender listed at all on their ID over the “X.” Similarly in April 2020, Abeni Jones wrote for The Washington Post about how they felt the “X” marker would increase issues of harassment that they already face while traveling and acknowledges that while it is nice to see the show of support, it will not fix the problems that it claims to address.

In reality, it would make more sense, be more inclusive, and ultimately be safer for all to simply remove gender from the majority of IDs entirely. There’s no truly compelling and non-bigoted reason for the gender to be listed there. One argument suggests that it can help medical responders, however, if this was truly the driving concern, then it would be more important to include blood type and drug allergies on ID, which would play a much bigger role in emergency medical care than a person’s gender ever would. In turn, if the gender representation is a binary one, there is a decent chance that it will be wrong or not reflect the physicality that the person reading the document expects from it, and if an “X” is viable, it demonstrates that someone’s gender identity is fundamentally not something that should affect their travel.

Neither airport staff nor a cop pulling you over to see your driver’s license needs to know your gender, whether that’s binary male or female, nonbinary, or another descriptor that a simple “X” could not properly communicate: and shouldn’t need to anyway.♦