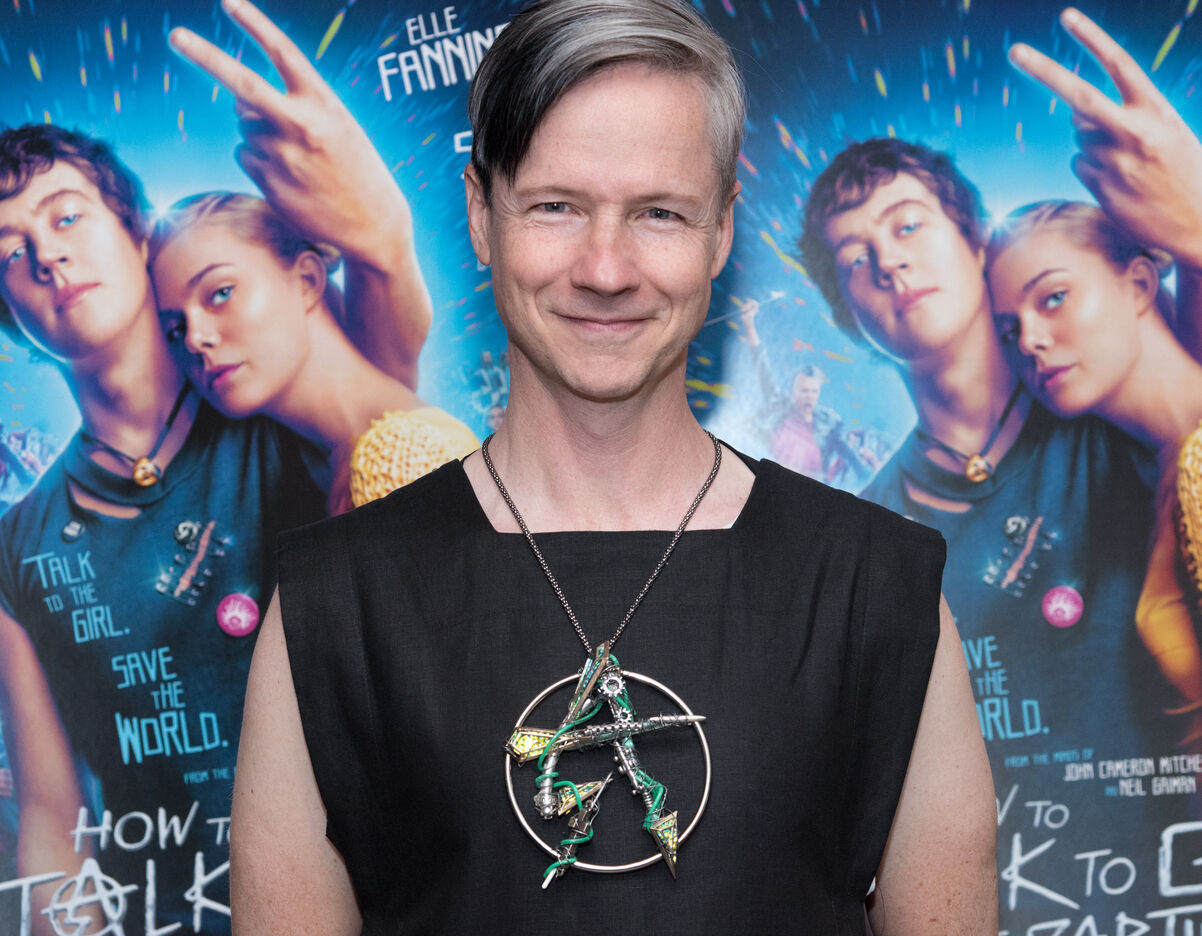

In 2018, it’s fascinating to follow the trajectory of the artists and creators who have contributed so much to queer cinema and culture over the last few decades. Some, like Bruce LaBruce, continue to work within an explicitly esoteric arthouse aesthetic. Others, such as Todd Haynes and John Cameron Mitchell, have gone the way of what LaBruce refers to as “prestige film.”

Mitchell, whose name is at this point synonymous with his Broadway hit-turned-cult-classic Hedwig and the Angry Inch, premiered perhaps one of the first explicitly queer films at Cannes in 2006 with Shortbus. Utilizing performers from the LGBTQ community rather than experienced actors, and displaying real queer sex on screen, Shortbus was as unapologetic as Hedwig, challenging heteronormative viewers to invest in a subculture they might not see themselves in.

For his follow-up, Mitchell took a radically different direction, though one in keeping with his theater roots. Rabbit Hole was an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning David Lindsay-Abaire play, starring Nicole Kidman (who also served as a producer), Aaron Eckhart, Dianne Wiest, and Miles Teller in his feature film debut. With a dark but poignant premise about death, survival, and parallel universes, the film won positive reviews, notable awards and nominations, and a standing ovation at its TIFF premiere.

Surprisingly, the indie queer Shortbus outearned Rabbit Hole at the box office and had a 2 million dollar budget versus Rabbit Hole’s 3 million. It’s unknown how much Mitchell’s new film, How to Talk to Girls at Parties, had to play with, but the adaptation of a Neil Gaiman short story of the same name is something of a Mitchell mash-up, with elements of his former works and interests coming together for a work that has A-List stars (Kidman, Elle Fanning, Ruth Wilson), colorful choreography, punk rock, and sexual fluidity. Set in the South London town of Croyden in the 1970s, Alex Sharp stars as Enn, a teenage punk whose friends are only interested in music, drinking, and sex. After leaving a show one night (helmed by Kidman’s punk impresario inspired by Vivienne Westwood), they happen upon a house full of extraterrestrials that are temporarily in town for research. Fanning’s Zan is among them, a rebellious alien who rejects the banality of her role in the familial commune. Once Enn and Zan meet, their love affair drives most of the story, which takes them between their two worlds.

Mitchell tells INTO he wanted to work in the UK, as the son of a British mother wholived there in the early ‘70s. He says he enjoys the British sense of humor, and that British actors can be much less frivolous than their American counterparts.

“Most actors in Britain are theater people so they have a real good professional way of working whereas sometimes American film people who haven’t done theater are very like pissy or they won’t come out of their trailer or if they come out of another work that just not as well behaved, you know?” Mitchell says. “Actors are working people. They’re like union people in the UK so you get more of a humility and let’s do the job and let’s do it well and not worry about all the crazy perks and cars and things.”

The early ‘70s world of English punk was also an exciting space for Mitchell to inhabit, as he has always been a fan of the genre and knows many major players. The film can almost serve as a comedic prequel to Haynes’ ode to glam rock Velvet Goldmine (which Mitchell was originally cast in but had to bow out due to Hedwig demands).

“It was really fun to immerse myself in the history and the movers and shakers and realize that women were – I mean it was still a very misogynist and kind of homophobic vibe, just like most of the world was,” Mitchell says, “but it was a more mixed gender and sexuality and Vivienne Westwood was kind of the godmother of it. She was a strong matriarch, which you know Nicole Kidman’s character kind of comes from. And there were great bands like the Slits and the Adverts and Siouxsie Sioux that were female led and some queer bands like the Buzzcocks that were queer led.”

There are queer elements to How To Talk To Girls At Parties, as one arm of the pansexual aliens (led by Wilson) are led by the sacral chakra in their pelvic region (which you can’t miss, as their outfits are adorned with orange right on their chest and genitals). There are as many colonies of the aliens as there are chakras, and costume designer Sandy Powell created specific looks for them based on those Eastern centers of spiritual power. Choreographer Lee Thompson and composer Nico Muhly worked to find how all seven colonies moved and sounded, creating distinct identities that could sync up when congregating.

“I told all of my designers, I kind of want aliens to feel like aliens from the ‘70s if you know what I mean – the way they look, because even aliens had a nostalgia for the ‘70s, so films like Liquid Sky and even Rocky Horror, which they actually are aliens you know,” Mitchell says. “Not exactly our aesthetic but you know that kind of ‘60s, ‘70s, plastic, new wave, Gary Numan, B-52’s. It was a designer named Pam Hogg, who we were influenced by. That ‘70s version of alien. You know Bowie, Man Who Fell to Earth, Ziggy Stardust. All of that is in there or influenced our aliens and our punks because without David Bowie there would be no punks or aliens.”

As for how queer Mitchell sees the film, or any of his work that might not have an explicit queer narrative, he finds that it’s something unconscious.

“I think it’s that if you have a queer life, your work tends to have a queer angle. You know, I don’t need to have every character be like me but the things that you deal with, I think the way you define queer is not so much sexuality as looking at life from the outsider’s point of view through a prism of gender, and we all know straight people who are queerer than our gay friends and we all know trans people who are straighter than our gay friends. It’s all a mix, right?” Mitchell says.

Take, for example, Caitlyn Jenner.

“I don’t know how queer Caitlyn Jenner really is but she’s on the spectrum so to speak. Sense of humor doesn’t seem to be part of it but there’s something there and she’s an outsider and she should have more empathy,” Mitchell says. “I mean, for me, being an outsider – for me an outsider without empathy is the most horrifying thing because that means you can’t identify with anyone else and you can’t see.”

How To Talk To Girls At Parties is less focused on the political than the fantastical ideas of love and revolution – of punk love in the face of conformity. That is inherently a queer narrative, one that is set to music and with bright, flashy spots amongst an otherwise dreary Croydon. If Enn and Xan can find a way to be together in a world that won’t allow for it, their attempt tomake it work is radical. All of these components together make for a very John Cameron Mitchell film.

I

I

Anyone who suspects that Mitchell has gone the way of mainstream only to lose his edge needn’t worry. He may create work that is seen as more accessible to a larger audience (the Kidman connection alone will allow for that), but the place where his directing (and acting, writing, and singing) comes from is deeply inspired by his queer worldview. That view doesn’t just mean how he sees and hopes to create queer lives and culture, but modern Trumpian America, and the greater political landscape.

“I’m always shocked when queer people find themselves saying something racist or when someone of a less privileged racial origin says something really homophobic. I’m like guys, really? Are you really going to find somebody else, put someone else below you so you can have someone to shit on?” he says. “I know some would say that’s a human thing to do, you have to have a hierarchy of who gets shit on and who’s more oppressed and who is less oppressed and therefore they can be more disrespectful. It’s like guys, it’s all a different kind of experience that each of us has growing up gay, queer, black, foreigner, an immigrant, yes. But if you cannot have mercy on someone else who is fighting their own battle, what is the point? Why not just sign up for the Trump parade?”

He calls out Milo Yiannopoulos for joining that parade “so he could get more hits and get more money and betray anyone and really hate himself to do it.

“And when there’s money and fame involved, they will sell their mom down the river and sell their brothers and sister down the river,” he says.

Mitchell isn’t trading queer people in – he’s looking to expand upon the notion of humanity while making sure queer people have seats at the table.

“Let us find the things that we have in common, the things that we feel, the things that we want, the things we give as joy,” he says. “The more and more we try to separate ourselves, the more we’re going to all be in our own little category with our own personal label alone and then Trump wins. Steve Bannon laughs while we destroy our allies so you know for me, it’s very much about finding common cause.”

“That’s why I like the Parkland kids, you know?” he continues. “They’re like the new punk because they’ve grown up actually with this over their head and it’s not a millennial panic of just, like, find your perfect social media picture or group and then just dive in there and hide out. I mean they had to be shot at, but I love that Emma Gonzalez. She’s a kid and she’s going to have a lot of pressure on her now because of that, but that is the kind of punk that I love. It’s like: fix what your parents fucked up as opposed to looking for more ways to separate ourselves.”

How To Talk To Girls At Parties opens in theaters this weekend.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox