Jordan Harrison’s Log Cabin, directed by Pam MacKinnon and running at Playwrights Horizons through this Sunday, is a toothless commentary on contemporary homonormativity that recapitulates its characters’ regressive politics even as it attempts, unsuccessfully, to point them toward a more enlightened future.

The play takes place in Brooklyn, covering the lives of a gay couple, a lesbian couple, and their FTM trans friend, Henry, as they contend with parenthood, privilege, and trans identity. The six years of the play begin shortly after New York State approved same-sex marriage equality in 2011 and continue through Trump’s election to the presidency in 2016.

The cast playing the two core couples — Phillip James Brannon as Chris, Jesse Tyler Ferguson as Ezra, Cindy Cheung as Pam, and Dolly Wells as Jules — deliver entertaining, three-dimensional, and hyper-realistic performances that keep the play buoyant for 90 minutes, but their characters, written to be fundamentally unlikable, don’t leave a fond impression after the curtain closes.

What makes them unlikable? They’re the kind of rich, Brooklynite gay people who donate to the Human Rights Campaign as the full extent of their political activism, who were content with the outcome of Obergefell v. Hodges as the endgame for gay liberation, and whose utter complacency and insularity leaves them totally shocked when Hillary loses the election. Worse, they’re aware of the LGBTQ+ movement’s punk-rock history, but their lack of a political conscience does little to rattle them as they drink mojitos in their brownstone apartments and cheat on each other, because, of course, none of them have heard of ethical polyamory — in this world, open relationships are, at best, a necessary but unfortunate concession to the lower gods of human frailty.

While these characters need to exist on the American stage, because they represent an ideological cancer within the LGBTQ community that must be excised, Harrison does little to meaningfully examine their behavior or hold them to account, choosing instead to lean on heteronormative platitudes like “marriage is a compromise” and “children are our future” as the evening’s chief takeaways.

Speaking of children, the only self-aware and well-spoken character with a conscience, Myna, is derided by the others, called a millennial child, and tossed out of the play two-thirds of the way through, immediately after delivering the most cogent critique of consumerism in the play. (It goes mostly unheard.) Harrison muddies the waters by compounding her frustrations with a violation of trust, by Henry, leaving us to wonder whether her (legitimate) criticisms have any bearing at all on her decision to leave the action for good. He’s even chosen to name her after a parroting bird, as if she can only mimic others’ words and thoughts.

In other words, Log Cabin‘s smartest character is portrayed as a triggered hippie with no dramatic use beyond how she reveals Henry’s misogyny and ageism, then makes Henry’s womb available for Chris and Ezra’s use.

Perhaps the biggest missed opportunity in the play has to do with its non-treatment of colonization as a useful site of investigation. Ezra opens the baby’s gift, and it’s meant to be taken as a funny quirk of his neurosis. The baby sleeps in a tipi, but there’s no discussion of tipis’ use in Native American culture or of Europeans’ centuries-old, violent treatment of indigenous communities, which continues to this day. Poor Henry is asked to go off of testosterone so his body can be used by Chris and Ezra to produce a baby. And Henry, in turn, agrees to participate, because he wants to use the body of the prospective child so he can participate in the identities and rituals of fatherhood. These characters participate in theft with no consequences.

And they steal from each other wantonly because their relationship to authority is corrupted. Time and again, their expressions of their deepest desires simultaneously deviate from a heteronormative playbook and harm someone they care about, as if that playbook is the only legitimate source of authority. Pam even cites what straight people have been doing “for thousands of years” as permission for Ezra to open his relationship with Chris. The most self-consciously “political” discourse in the play has to do with which words belong to whom and who’s allowed to say what. Chris isn’t even allowed his expression of black male rage — he has to eventually apologize for his outburst in order to warm Henry up to the idea of going off T and lending his womb.

In the end, we’re made to believe that these characters’ only link to redemption lies in their children, and what they will eventually accomplish, effectively absolving the adults of any responsibility. But what of the queer adults who don’t wish to have children? They may not exist in the world of this play. Regardless, Log Cabin places no value on a non-reproductive way of being, nor on a serious reckoning with the violence of centrism or capitalism within the LGBTQ+ community.

Who is Log Cabin, marketed as a satire, for? Is it for rich, cis gays, to teach them about privilege, trans rights, and mutual respect in the context of a relationship? Is it for critics of capitalism, to show them that their contributions to the project of queer liberation have no meaning, since it’s up to our kids to save us from within the machine of uncritical homonormativity?

As the meme goes, “Satire requires a clarity of purpose and target lest it be mistaken for and contribute to that which it intends to criticize.” Log Cabin, lacking both a clarity of purpose and target, misses the mark, both in its marketing promise and in every play’s responsibility to do no harm. Instead, it traps its audiences in a 90-minute Cobble Hill hellscape in which impotent, gay cries of “Whatever shall we do about the future?” sound an awful lot like “Let them eat rainbow avocado toast.”

Log Cabin plays at Playwrights Horizons, 416 West 42nd Street, through Sunday, July 15. See www.playwrightshorizons.org for details.

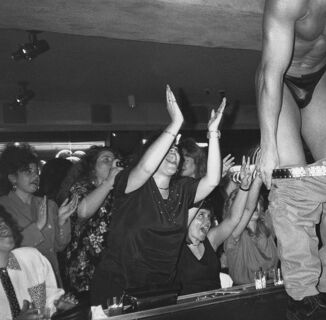

Images by Joan Marcus

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox