“Why is aging in homosexuality always tragic, like ‘Death in Venice.’” –Casey Spooner (47, artist)

A man I meet at the gym eventually tells me he is 53. Michael is toned and friendly, shockingly handsome, with a head full of salt-and-pepper hair. After several weeks of banter, I realize he has been flirting with me, cruising me in the locker room, and I am embarrassed by my cluelessness, more comfortable making passes through a switchboard of phone apps. Though we are both gay, we have been speaking startlingly different dialects across a generation gap.

When our ages finally come up, he confesses his with the same note of apprehension I hear from my peers when we leave a party before 10pm; when we choose to limit alcohol intake; when we talk all evening about work; when we elect to stay in altogether; when we have another birthday. An elegiac tone that says, We are getting old.

Meanwhile, I bristle when he asks, “Does that make you a millennial?” because I’m wondering what that label tells him about me. I’m an avid reader, always looking to books and essays to better understand myself and the world, and from what I can tell, the millennial scourge provokes the disdain of many for what they call our “extended adolescence.”

Born between 1980 and 2000, my generation is said to have stagnated; technology has turned our dating pool into an ocean. The only upswing, according to Jessa Gamble in The Atlantic‘s 2016 piece “The Cognitive Benefits of Being a Man-Child,” is what’s called “neurobiological capital.”

Possibly the only form of capital we millennials can lay claim to, it aids in “navigating other people’s needs and emotions, pushing past failure without losing determination, and connecting immediate actions to long-term consequences.” This is the lone pearl we carry with us as we cross the threshold into middle age in 2020an event that will occur regardless of whether we’re stuck, whether or not we want to grow up at all.

But who does? I have seen Michael’s Scruff profile, which claims he is 45, a white lie that moves him from being a young boomer to an old gen Xer. Baby boomers (or typically those born in the 1940s through mid ‘60s) have been fighting old age since the tail end of the 20th century. Medical advances have enhanced quality of life well into one’s 60s and 70s, and every health and wellness brand on earth has pitched some listicle about staying young at 50 and even 40!

Gay men are “scared of aging more than a lot of other people would be,” says University of Texas-San Antonio professor Christopher Hajek. Paul Bisceglio summarizes Hajek’s interviews with middle-aged gay men in 2014’s “How Gay Men Feel About Aging” for Pacific Standard, adding that younger guys “don’t have landmarks for progression through life that a lot of heterosexual people have.” Which is trueat least for me.

The fear of aging can pervade even the smallest of talk with self-deprecating tics, but Michael’s worries also touch on a broader concern of irrelevancy.

“Young guys don’t always notice older men,” he tells me. “Lots of times they won’t even look at you. You start to feel invisible.”

The rise of what author Mike Albo described for The Cut as “daddy” culture might be shifting this in a sense, so I hope those of us with an eye for guys a decade or three our senior are beginning to appreciate them as more than just a sexual ideal.

Up till now there haven’t been a lot of role models available to show how one ages gracefully as a gay man, and Michael’s generation is still feeling the reverberations of cataclysm.

“Arthur Less is the first homosexual ever to grow old,” declares Andrew Sean Greer in his sweet and comic novel Less. “He has never seen another gay man age past fifty they died of AIDS, that generation.” The hero is a milquetoast writer entering his 50s as he travels the world to avoid a former lover’s wedding, and Greer gently examines the ways “Less’s generation often feels like the first to explore the land beyond fifty. How are they meant to do it?”

After years of reading op-eds about the alleged arrested development of millennials, I can relate to Less, and I continually hear his sentiment echoed by gay men facing middle age. The script we’ve been given is no longer adequate, if it exists at all. Everywhere we are told to resist the aging process, to feign youth until death.

Yet, as the great Oliver Sacks once said, “I don’t so much fear death as I do wasting life.” In this new Oz, more queer folks are out and fewer of us are dying. We are no longer beholden to closets and death sentences. I firmly believe we are more than our trauma, so I am always on the lookout for joy in gay lives. There is joy in longevity, but we’ve long been trained not to see it.

That Sacks quote is the epigraph to Bill Hayes’s terrific memoir Insomniac City. Hayes crafts a captivating and impressionistic portrait of his midlifeof losing a long-term partner, moving to New York City, becoming a street photographer, and falling in love with neurologist Oliver Sacks. Hayes, entering his 50s, consistently marvels at the life force of New York and its denizens; Sacks, entering his 80s, is filled with wonder for the science of life itself. They are for each other a refreshing burst of energy.

Aging isn’t the point of Insomniac City, but it emerges in its subtext as Hayes encourages readers to face the world openly. Romantic and inspiring, the book demonstrates a hope that midlife promises more than just loss and decay, that there is still magic throughout one’s golden years. And for myself, it was heartening to witness such a profound depiction of gay men building their lives together, with an enduring intimacy, a certain frank ongoingness. Reading it meant falling in love over and over again with Bill and Oliver’s livesand my own.

Sacks lived to the age of 82, when he died of terminal cancer in 2015. While his is another painful death for Hayes, Sacks wasn’t naive. In the 2013 New York Times op-ed “The Joy of Old Age. (No Kidding.),” he recognized the threat of dementia and strokes, the absence of friends who have already died, even as he wrote, “I am grateful that I have experienced many thingssome wonderful, some horrible.” Perhaps one of the most wonderful being Bill, who came into his life after 30 years of closeted celibacy.

I find so much to admire in both for the ways they embrace life at every age. Hayes’s work resonates with joy and wonder, even as he grieves for the men he has loved most. Sacks’s deep empathy and curiosity made him one of the most beloved doctors in the world. And at home, in Hayes’s depiction, he exudes boyish charm and mischiefas, it seems, does Bill: “O, when I accidentally dropped a carton of cherry tomatoes on the floor: ‘How pretty! Do it again!’ So I do.”

As I’ve gotten to know Michael betterat the gym and the movies, over coffee or dinner with our partnersI recognize a similar playful tenor to his personality. He’s been with his husband for decades and has a successful career, but he’s not so serious as critics demand millennials become if they want to be considered adults. He is for me a living, breathing example of how to be a well-adjusted and aging homosexualdespite any fibs he may tell on social apps. What’s more, he’s blazed a path apart from heterosexual landmarks, and is now someone with whom I can share questions and curiosities, hopes and concerns about my future, unrelated to the normative zeitgeist. As much a friend as a role model.

Michael is, in truth, a composite of several men I’ve become close to in the last couple of years. These are men whose dispositions seems to reflect a textbook definition of neurobiological capitalthat attention to the needs and emotions of others, that persistence in the face of failure, that willingness to welcome the world even as it may hurt you.

So if that’s the through-line to just growing up already, and if millennials are swimming in such capital, maybe middle age doesn’t have to be so fearsome. Maybe we are instead poised on the verge of possibility. This is our chance to queer the fear of getting old and embrace the signs of aging. Our longevity has been hard won.

Aging is inevitable, and it won’t always be a pleasant journey, but is there any use fearing it? Fear complacency. Fear calcification. Fear wasting life. But not aging, not death. We have the choice to turn a stony gaze toward the effects of time in futile defiance, or we can let them wash over our soft flesh, happy to feel it all. Somewhere down the line we are all going to get old, but perhaps by then, old won’t seem quite so old.

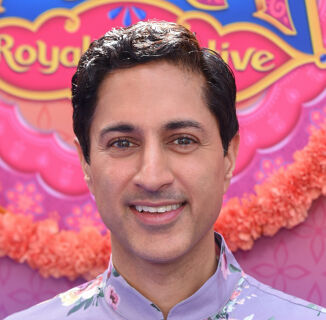

Header image via Getty

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox