In September, during a Senate hearing about book bans in public and school libraries across the country, Louisiana senator John Kennedy (R-LA) read a passage from George M. Johnson’s often-challenged queer memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue. Kennedy read the excerpt, which describes the author’s first time engaging in anal intercourse through thoughtful prose, using an intentional blend of contempt and disgust.

Illinois Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias, who banned book bans in his home state, responded by saying the words were “disturbing,” but “especially coming out of your mouth.” It was disturbing — but not for the reasons Giannoulias or Kennedy might assert. Kennedy was trying to smear the words, straight from one of the most challenged books in America, as inappropriate, despite the book recounting a queer teen’s real-life experience.

Sen. John Kennedy having a very normal one during this Senate hearing pic.twitter.com/TafATlG1l7

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) September 12, 2023

Censoring queer art is nothing new in America, especially when done in the name of protecting youth from LGBTQ+ stories. As explored in the 2006 documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated, the film ratings board has always disproportionately punished queer films, such as Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry, with NC-17 ratings, limiting their commercial prospects and potential theater showings.

Entertainment with an edge

Whether you’re into indie comics, groundbreaking music, or queer cinema, we’re here to keep you in the loop twice a week.

That same spirit is at work in America now. Despite all the work that queer writers, editors, agents, and industry insiders may put into creating queer content, a small group of people — politicians and religious right-wing activists — can and will construct walls between these life-saving stories and queer youth, amplifying writing from an act of creation into an act of resistance.

While conservatives continue to try to do everything they can to stop queer youth from accessing books, the publishing industry continues to produce them, leaving many imprints in the precarious position of releasing groundbreaking titles that might be banned or challenged.

“I started writing because reading these stories, reading about queer people in my school library was so important to me,” Camryn Garrett, author of young adult novels such as Off the Record and Full Disclosure, told INTO. “I didn’t realize that I was queer until I was reading young adult [YA] books about girls kissing. And I was like, ‘Oh, like, that’s an option.’ I think that’s part of why these books are being banned because they provide options to young people.”

RelatedDiscover captivating LGBTQ+ YA books filled with self-discovery, romance, and inspiring tales that will tug at your heartstrings.

Since anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric began to ramp up in the summer of 2022, a common weapon in conservative arsenals has been the book ban. Attempts to ban books doubled last year, and in the first half of this year, the number of books challenged went up by almost 30 percent—approximately one in four challenged books prominently featured LGBTQ+ characters or themes.

The term “book ban” is both ubiquitous and vague, as it can mean many different things; it can include books being placed off-limits for students in libraries in classrooms, investigated by administrative boards, taken off library shelves, removed from reading lists and official school curricula, or even re-categorized for adults only, referred to as “soft censorship.”

A Washington Post report about book bans found that 42% of filings targeted titles with LGBTQ+ characters or themes. But of the more than 1,000 challenges analyzed, the majority were filed by just 11 people.

The attempts to ban books nationwide are being led by a small coterie of right-wing activists, whose actions can rip a book off shelves and out of reach from those desperate to see themselves reflected on the page. These people may object to an author’s work, conceiving of the author as a sole entity writing an entire book, but in reality, a book represents a community of people putting in countless hours to give readers a story they believe to be important.

Garett said that after taking months to write and rewrite her books, each had a collection of people who read, edited, and nurtured the title. That includes her agent, editor, multiple copy editors, the book’s cover designer, the people who marketed it, developmental editors, sensitivity readers, friends who read her work, and more. Garrett, who attended film school, likened writing a book to producing a film, though a book is often perceived as a solitary endeavor with the the author’s sole attribution.

While people who ban the books may think that, for example, they are banning the story of a Black, queer person, the reality is that many contributors from diverse backgrounds and viewpoints worked to bring it to life. “It is frustrating to see people act like one writer with an agenda is trying to brainwash kids,” Garrett said. “A bunch of people have to believe in a book, the story, and the message for it to exist.”

A ban, however, can often be perfunctory; if a parent doesn’t like something in it (often out of context), they can challenge the book to be removed from library shelves or recategorized for adults only. Bans can sometimes take the form of criminal proceedings, as well. In 2021, two years before the current string of LGBTQ+ book bans, a school board in an undisclosed state filed a criminal complaint against Johnson for the content in All Boys Aren’t Blue. “That was when I knew this isn’t going away,” the author told Time. “And they’re trying to use the criminal justice system, which is often the route that they go when they feel like things aren’t going their way. They try to criminalize you.”

Standing opposite the vast majority of parents who oppose book banning is one Florida-based group, the ironically named Moms for Liberty, which plays an outsized role in the national book ban debacle. Jennifer Pippin, a founding member of Moms for Liberty, recently said that she challenged All Boys Aren’t Blue based solely on a Facebook post containing what she called a “graphic anal rape scene,” conveniently eliding that the book also discusses consent, agency, and sexual abuse. Johnson, the author, told NPR that the book helps readers understand abuse and name abusers, as well as “feel validated in the fact that there is somebody else that exists in the world like them.”

‘Banning books is banning information’

About one in five members of Gen Z identifies as LGBTQ+, according to a 2022 Gallup poll. Not only are they living through book bans, but they, along with Gen Alpha, are living through an unprecedented assault on the rights of trans and gender-nonconforming people. It’s no coincidence, says Noah Grey Rosenzweig, a literary agent at Triangle House, a boutique literary agency founded in 2019, that recent book bans have coincided with a larger anti-queer push that puts a deliberate chasm between queer youth and the tools they might need to flourish, which may include role models for gender expansion, such as drag queens, and gender-affirming care.

“Banning books is banning information, and banning gender-affirming care is based on faulty information,” Rosenzweig told INTO in a phone interview. “A lack of information is what gets a lot of people riled up.”

As an agent, Rosenzweig’s role is to be a conduit between authors and the auspicious publishing industry, which can be arcane and difficult to navigate or, as the New York Times recently described it, “opaque and intimidating.” That extends to everyone who is not a celebrity, politician, or influencer, let alone people who are traditionally shut out or underrepresented in traditional media, including young queer and trans people who may not have access to editors, imprints, and more.

A 2019 report from independent publishing company Lee & Low Books found that the publishing industry was overwhelmingly white, cisgender, and straight, with data taken from a survey of nearly 8,000 respondents. When it came to sexual orientation, about 81% of people who responded were heterosexual.

Publishing, a notoriously low-paying industry that adds to its lack of diversity in terms of race and class, complicates matters further. Low-paying jobs often result in the sector “self-selecting for people who don’t necessarily need to live on a salary alone,” explained one editor at a midsize press who remained anonymous to Publisher’s Weekly in 2016.

Despite the challenges, both Rosenzweig and Ayla Zuraw-Friedland, an agent at the Frances Goldin Literary Agency who identifies as queer, pointed out that LGBTQ+ stories and characters have gotten more diverse and complex in recent years, allowing queer characters to step out of the background and defy stereotypes. It’s not just that characters are queer; they have become more multi-faceted. The New York Times recently wrote about Payback’s a Witch, a book about two female-identified witches who fall in love.

“There are entire parts of the country where kids aren’t able to access these kinds of more complex, rigorous stories,” Zuraw-Friedland said. “It is terrifying to think about an entire generation of kids in Florida, in the Carolinas, in the middle of the country, not having easy access to these things.”

Even with the sheer volume and intensity of anti-queer laws making their way through state legislatures nationwide, that doesn’t mean that LGBTQ+ youth will stop learning about queerness. ”I was on the internet as a teen, and you do find what you’re looking for most of the time,” says Zuraw-Friedland — but for some agents, this nationwide push against queer stories has been felt in their day-to-day jobs as people who are in charge of making sure these stories get into readers’ hands.

RelatedBook bans can’t stop us

In May, PEN America (a nonprofit that unites writers and allies to celebrate and advocate for creative expression), alongside several publishing houses and authors, filed suit against Florida, which removed over 300 books from shelves last year. It’s also one of the states (along with Texas) where Garrett’s books have been challenged. The chilling impact has meant fewer bookings to discuss her work directly with students, which has the double effect of hurting Garrett’s finances and limiting the time students can spend speaking with queer role models.

As book bans escalate, Garrett hasn’t stopped writing, but she does pause to consider whether her work will be censored. “When I’m thinking of pitching a book to my publisher, I get more nervous,” she said. In a way, even this hesitance shows how insidiously successful these bans have been, sometimes even convincing queer authors to doubt their place in the world or whether their ideas are worth putting to paper.

Just as Garett continues to write, Rosenzweig feels called in this moment to continue searching for authors and helping their stories and ideas become reality. “I can’t think of a time when it was easy to be queer,” they said. “I think queer people persevere, as much we shouldn’t have to, and our art and literature do, as well.”

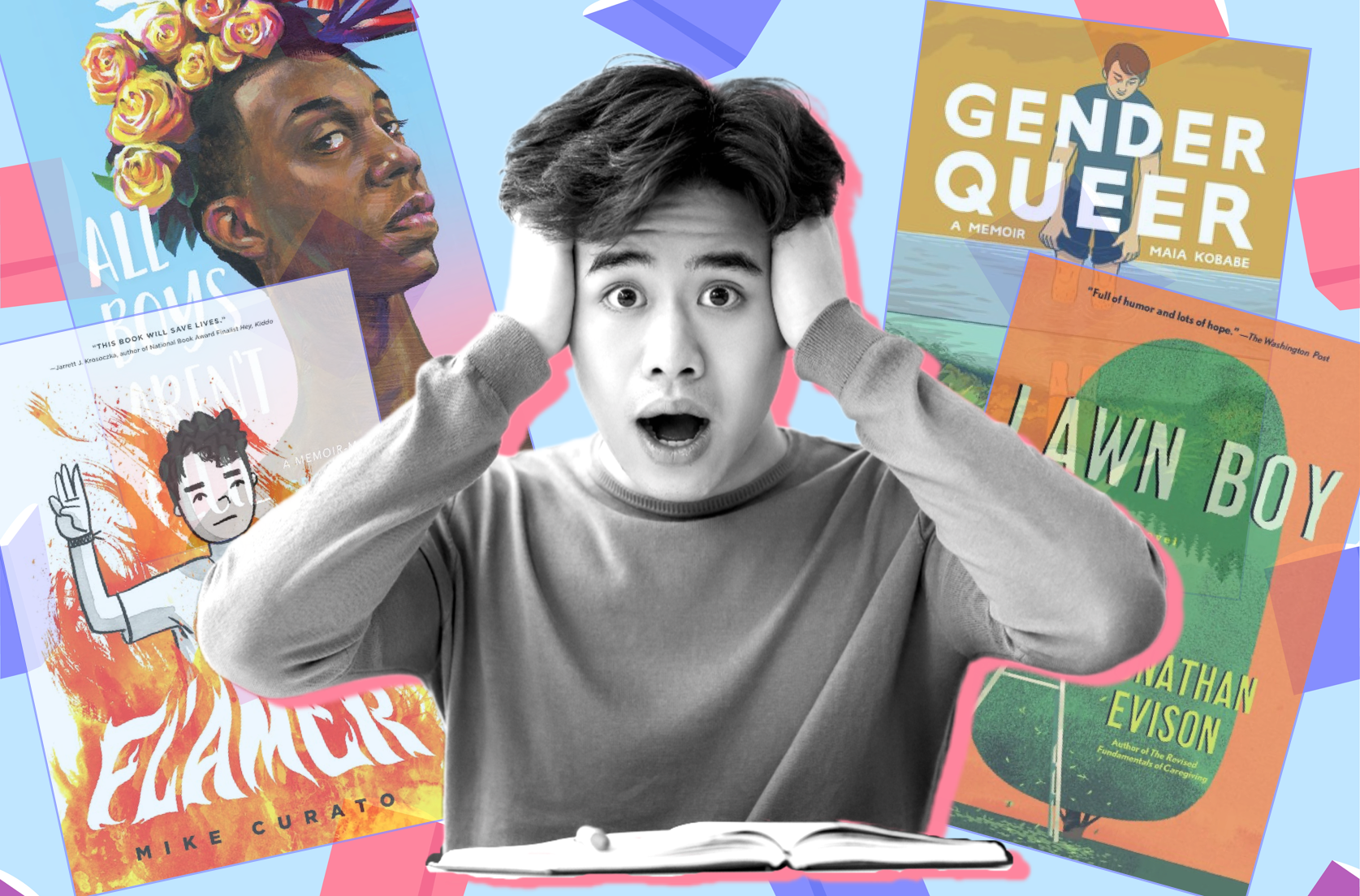

Feature photo illustration by Matthew Wexler. Photo: Shutterstock