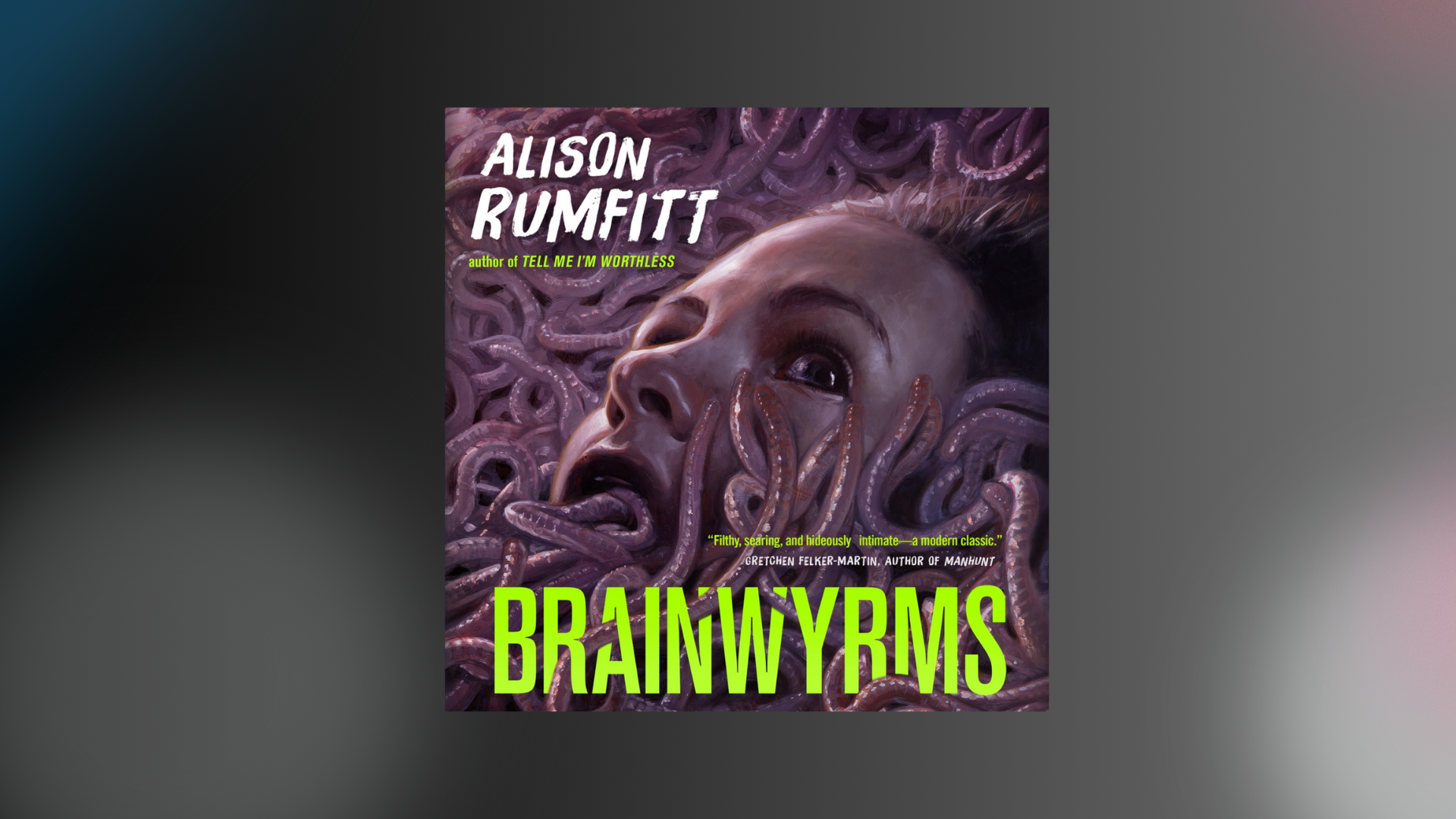

On Alison Rumfitt’s Brainwyrms

People love to cite J K R*wling as the queen of TERFs, but one hardly need look across the sea for institutional implementations of transphobic rage. I am becoming a broken record as I write this. Transphobia is bad. You should be horrified. Give me a like and engage with my poor frail trans body. Tell me I’m pretty, tell me I’m worthless. Fulfill my spit kink, fulfill my impregnation kink. I go to the doctor and say I am a good penitent trans girl worthy of surgery, but I daydream about the end of empire. I am aware—have been made aware—each time an author comes out as a “gender-critical feminist” or style guides declare TERF a “slur.” To be fair, my whole life is a slur at this point. I have engaged in respectability politics too long in the vain hope that more mainstream outlets will hire trans women book critics. (But Andrea Long Chu! you cry. Reader, I am aware. But even she has been victim to gruesome online attacks and a transmisogynistic tirade by beloved trans academic Jack Halberstam in Transgender Studies Quarterly.)

Horror asks us what we would do in a horrible, no-win scenario and then attempts an answer. But what happens when horror and real life converge? Writer Alison Rumfitt continues to ask this question by laying the roots of fascism at our feet, unafraid to dredge up its depths of filth. But this isn’t your filth of yesteryear; no one in a Rumfitt novel is as merry as Divine in a John Waters movie. Instead, Rumfitt’s characters are on the verge of extinction. Self-destruction is a prerequisite. Trans women can’t get it together, trans men are nearly always ready to change sides, and TERFs are capable of horrific violence both online and in person. Can writing such horror prevent it?

Brainwyrms, Rumfitt’s sophomore novel, is even more gruesome than her first, the haunted house redux Tell Me I’m Worthless. Body horror is the main thread of Brainwyrms, and its title should be taken literally. Wyrms as long as nine feet await you, reader. Just wait—or, as Rumfitt giddily suggests halfway through the book, take a break and drink a cup of tea. Reading about bombings, murder, and childhood sexual abuse—all core themes of Brainwyrms—is not a lighthearted task. But if the conceit is less structured and more gruesome than Rumfitt’s first novel, it does eventually deliver on a fascinating premise.

Related:

Anne Hathaway and Thomasin McKenzie have scary, sexy chemistry

In upcoming thriller “Eileen,” Hathaway is finally stepping into a sapphic role.

Much of the book is told through an omniscient narrator who leads us through the life of Vanya, a Polish nonbinary person, up to the point when they meet their lover Frankie, a jaded trans woman. Abused by their brother and abandoned by their mother, Vanya runs away early to the mysterious fetishist Gaz’s commune, where Gaz begins infecting an underage Vanya with tapeworms and other parasites. “I don’t let things inside of me which I do not love,” Vanya says when Gaz begins the process. This is typical—Vanya’s complicated gestures towards gendered embodiment often lead them into danger. Whether through desire or thinking about having a dick, it is difficult to know what to make of the relationship between Vanya’s feelings about gender and their betrayal of the trans feminine people in their life.

Lovers Frankie and Vanya meet on the dance floor at a rather sterile kink party. Frankie has an impregnation fetish and Vanya gets off on parasites. Neither of them can tell the other what they really want, so instead Frankie f*cks Vanya in the bathroom and pisses in their mouth.

Before we meet these two, the author addresses the reader in a brief autofictional content warning underscoring how close this dystopia is to our own. She tells us she is cis, that she is forced to write about transphobia because of our contemporary political climate, and that she knows the TERFs are coming for her. From the near future, she tells us the end times are near. Brainwyrms is hardly sci-fi besides its mystical parasites. This dystopia is close at hand. TERFs bomb gender clinics and stab trans women in broad daylight. TERFs claim to know the truth: “The world is not a place you make, the world is a place you are made by.”

We learn that Frankie used to work at a gender clinic that was bombed. In painful prose, Frankie witnesses (and subsequently replays) a cis woman getting ripped apart and decapitated by shrapnel from the explosion. In this world, sex is one of the few remaining outlets for fantasy. F*cking can make the nightmares recede—or come to the fore. Frankie and Vanya’s erotic dynamic is interesting, like an infected wound that won’t heal. As with Tell Me I’m Worthless, Rumfitt writes about the antagonisms between trans women and trans masculine people, though her point in doing so isn’t always clear. (Don’t worry—there’s a theyfab joke.) Frankie is Vanya’s top, until she wants them to f*ck her as if they had a dick during a fated party. Vanya says that makes them dysphoric but eventually relents, only for worms to appear in their genitals. It’s interesting to watch a trans woman top a trans guy—so little is written about sex between the two that the public consciousness doesn’t even seem to think trans men and women can f*ck. (Eliot Duncan attempted in 2023’s Ponyboy, though your mileage may vary.) Vanya and Frankie’s dynamic could be described as “toxic” though Rumfitt’s jeers at us that this is an oversimplification. Over the course of the book, who’s “on top” continually shifts.

Rumfitt’s prose struggles to come online at first, reading like an action novel with multiple experimental interludes; she inserts forum posts, texts, and short stage plays onto the page, mirroring the fragmentation of the written word in our current social media era.

Grace Byron

Transphobia is everywhere Frankie goes. Men turn out to be the siblings of famous TERFs like children’s book author Jennifer Caldwell. Cis women who hook up with her say “Stay safe out there and don’t get murdered,” parodying the popular true crime podcast My Favorite Murder. Writers like Rumfitt and Gretchen Felker-Martin expose the unnerving fact that cis women are just as capable of transphobic violence as men. Perhaps even moreso, they suggest. Suggestions are often warnings.

As Brainwyrms continues, the chapters grow shorter as Vanya’s teenage life takes over the novel. Rumfitt’s prose struggles to come online at first, reading like an action novel with multiple experimental interludes; she inserts forum posts, texts, and short stage plays onto the page, mirroring the fragmentation of the written word in our current social media era. The internet, we’re reminded, is the “primary source” for the fetishist, a “vast lake.” But as Vanya digs for fellow parasite enthusiasts, they discover “it’s tiny. It’s the same ten or so things posted over and over again. Sure, the lake is huge, but there is a particular type of fish that lives in its depths, and that type of fish is rare.” Rumfitt is adept at writing about youth culture, both the highs and lows. The text sings when she exposes the shards of joy and shame that seep into trans childhood. At one point, Rumfitt explores the story of a young trans boy who has a crush on a young trans girl. It’s one of the few moments of possible repair—until tragedy strikes.

Ultimately, no one escapes unscathed by the brainwyrm plague. The TERFs have a parasitic orgy led by Caldwell, the infamous children’s book author. TERF theory in general, Rumfitt reminds us, is a sex thing. Being normal is a sex thing, going to work is a sex thing, everything is a sex thing, so of course the worms are a sex thing too. Sex and power are inescapable. Even writing this book is a sex thing, Rumfitt tells us. On the destructive path our world is on, we may not like the climax we’re squirming towards.

It’s hard not to read Frankie and Vanya’s quarrel as a tet-a-tet of oppression just like the two lovers in Tell Me I’m Worthless play out. Is this division a critique about having allegiance to transmisogyny? Is it simply someone caught up in their own trauma?

Rumfitt doesn’t paint a simple picture—Frankie is certainly not an ideal girlfriend. No one wants to write a perfect, pretty trans girl. Why should they? ♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox