“I had grown up without any lesbian role models, and so I had gone out in search of them.”

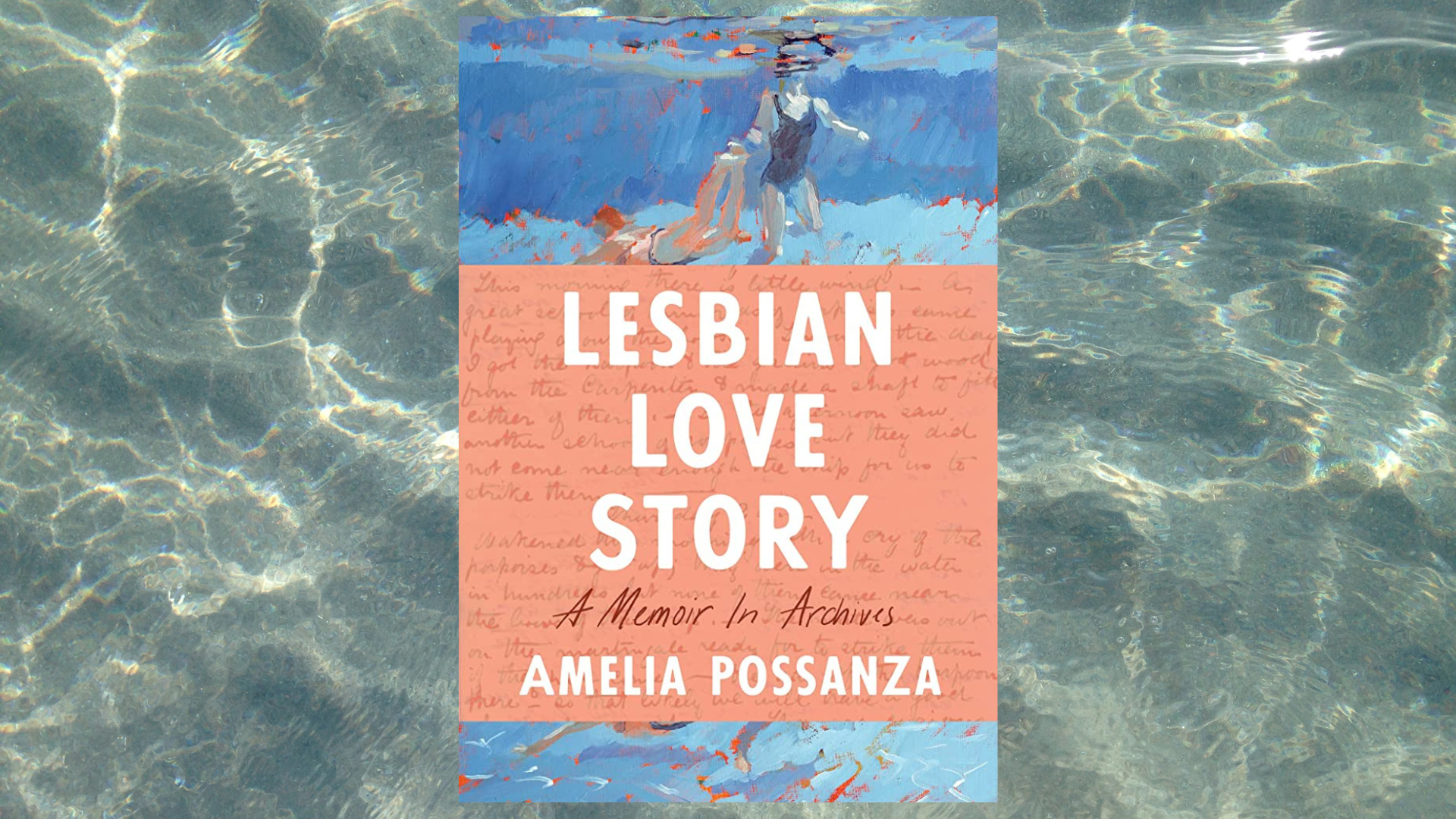

“Lesbian Love Story” —part memoir of a queer woman’s life; part meditation on how so few historical documents have been left behind as clues to our sapphic past— is tangible proof that queer women have always been here. Author Amelia Possanza breathes life into these stories, ensuring that we remember lesbians of the past as lovers, carers, and rebellious, talented human beings who gleaned more from life than the world was ready to give them.

Starting out, we meet Rusty, who “should be remembered as one of the forefathers of contemporary drag culture”, and specifically as a pioneer for drag kings; We also meet Mary Casal, who fell in love in a hotel lobby when she was distracted by “the most beautiful hands” she’s ever seen, and whose autobiography, “The Stone Wall,” likely inspired the name of the bar where the 1969 riots ignited. We meet Gloria Anzaldúa, whose Chicana feminist works Possanza studied at college, but whose queerness her lecturer had never mentioned, despite Anzaldúa’s work being inextricably linked to her politics in community with other lesbians working to change the world. In her exploration of the poet Sappho of Lesbos, Possanza reminds us that the origin of the term ‘lesbian’ embraced “irrevocably” and with equal enthusiasm people who don’t identify as women and people who don’t exclusively love women.

We meet “the original U-Haulers,” Black working-class dancer Mabel Hampton and Lilian Foster, “stud and wifey”, whose butch and femme presentation—were they to be seen walking in public hand in hand—could be mistaken for the straight couples they modeled a life on; We meet Amy Hoffman, one of countless queer women who supported the gay men they called friends and family, who “sat by bedsides, who held dying bodies, who cooked and cleaned, who remember.” Possanza compares Amy’s life to her relationship with her own gay male best friend, John, who “will live” and grow old alongside her because of his access to PrEP. She writes about the complex, difficult privilege of knowing that she and John get to write a new chapter on friendship between gay men and lesbians.

Related:

6 Underrated Queer Reads That Will Blow Your Mind

Queer literature is a lot broader than these obligatory Pride lists make it out to be.

To say Lesbian Love Story is a record of people who love like us feels like underplaying the significance of what Amelia Possanza has built here. It’s a history of wrongful arrests and institutionalization, of intersection and erasure, of claiming the spaces you belong —whether they want you there or not, whether they’ll admit to you standing there or not. This is a vital historical document, collecting lost stories of the past, but also representing an extraordinary voice of the inclusive contemporary lesbian’s view on the future. These love stories —“each a match struck against the grain of their eras until their lives burned bright”— are reimagined through an explicitly and uncompromising lesbian lens, finally. Possanza goes one step further by using each lesbian’s own words as much as possible. “Lesbian Love Story” is exquisitely written, filled with lyrical sentences where the author excels at capturing the beauty and “rhythm of loving beyond the grasp of men.” In between, she shares stories of her first kiss, her teenage crushes, her desperate longing for a connection, and the relationships that ended before and during her quest to write this book.

To say Lesbian Love Story is a record of people who love like us feels like underplaying the significance of what Amelia Possanza has built here.

Many lesbians featured in this book died without the dignity of being acknowledged for who they truly are: “without children and without public recognition of their contributions to history, leaving no one to preserve their documents, from birth certificates to photographs.” History is filled with lesbians who, for their personal safety, left out the names of their lovers (and the thrilling details of queer eroticism that we crave) in the traces of life they left behind. History is also filled with record keepers, who may not have seen themselves as historians (in adoption agencies, prison logs, hospital files, and property tax documents) but nevertheless erased and ignored queerness to preserve their restrictive, conservative institutions. With Lesbian Love Story, Possanza rights those wrongs. She does it with so much care and generosity that it’s clear she sees herself as a loving descendant of these brilliant women. The author’s research embodies the true meaning of family in its most queer sense. She tells their stories the way they deserved, the way they would be if they had lived in a world that wasn’t actively erasing their existence.

“Lesbian Love Story” is for anyone who has ever laughed at a “they were roommates” joke, or noticed an absurdly obvious queer moment where historians have said “these two look like very good friends.” It’s the historical collection we deserve. This is a queer person doing what historians have always done —recalibrating history on their terms. Amelia Possanza simply turns that dial right back to where it started: Super queer. Where history has always thrived and danced, dodging the spotlight until it’s safe. “I don’t have a history degree,” she writes, “but I do have lived experience, and that should make me just as qualified as the scholars who have come before me.”

I want to note specifically for anyone with concerns that with its provocative title, “Lesbian Love Story” may read as exclusionary: Fear not. This book is incredibly inclusive. Possanza tells us early on of her privileges as an upper-middle-class, college-educated, cis white woman. And as someone who is neither of those things, I experienced her writing as conscious of her privilege and in love with her subjects. She makes an effort to research the contexts, struggles, and stereotypes that society forced onto women of color. She quotes scholars and authors and historians of all types, announcing her bias and letting the reader into all her concerns and uncertainties. Most of all, I loved that Possanza uses her privilege to call out the devastating prison, police, military, and psychiatric systems that blatantly disregard the lives in their hands.

The language in “Lesbian Love Story” is welcoming and expansive, as it should be. For much of the book, the author describes her romance with a person who uses they/them pronouns. She shares stories of people throughout history who loved like we do, crossing the lines of gender identity and gender expression. Possanza acknowledges early on that for many the definition of ‘lesbian’ is centered around women who love women, but that once she met each of these lesbians (in her own way, through research road trips, and hearing them tell their stories on tape) it felt more true to suggest that not all of these people would have chosen the word ‘woman’ if they had access to the language of today. She admits that the people reflected in these stories may not identify with the word ‘lesbian’ either, especially since sapphic sexuality has been so entangled with gender presentation until recently. Along the way, Possanza fiercely eviscerates any argument for TERFy movements and narrowly defined concepts of lesbianism, past or present. Here, lesbian “is not a fixed identity but rather a word that marks my lineage, a flag raised to help me rescue these ancestors from obscurity.”

Possanza writes about these lesbians like she spent time in person with them, and we begin to feel the same way. She endears herself to readers in the various confessions of how emotionally invested she was in following the queer women’s stories as she researched. “I measured my meet cutes against [theirs]”, she tells us, admitting to daydreaming and comparing details in the way romantics often do. We smile to ourselves as we follow these journeys to freedom, and towards a new kind of love. We travel to women’s colleges like Vassar and Wellesley which “created just the right circumstances for women to fall in love with each other.” The all-women dances and close friendships between roommates from which all sorts of new customs blossomed, including the popular use of the term “crushes.” It’s hilarious and fascinating to read about how these friendships were encouraged as a stepping stone to marriage, a practice run to their lives with men.

It’s not all roses and bouquets of violets, though. Accounts of sexual abuse in private diaries present as unambiguous evidence of the risks they were taking, as well as documenting the horrific implications of a world where women aren’t educated about their own bodies. We see the strength of these women in the burdens they’ve had to carry, and in the way they spoke or acted out against them. Possanza does not shy away from the truth of the taboos and trappings of the past; Instead, she rebels by giving them “the kind of lesbian happily-ever-after I so rarely get to see in history books.”

When Amelia admits to John that she had begun this project to find lesbian role models, he understands. He believes that many gay men struggle with depression and addiction because they lost an entire generation of role models; No longer afraid of AIDS, they panic at the idea of a future unimagined. “I had lost my role models in the abyss of the archive,” she writes, “He had lost his to a pandemic.” At the end of the book, they stand together at Mabel’s grave, discovering that she is buried with Lilian and with someone named Alma Love, who they don’t recognize as having any relation to Mabel. They quietly rejoice at this confirmation that even in death, queer people rewrite the ideas of family, the bounds of friendship, and reimagine an inspiring vision for our future.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox