Right now, it feels like an early ’90s resurgence. Sinead O’Connor and the Rugrats are all over the media, and ACT UP is in the news again.

The latest book from writer and ACT UP Oral History co-director Sarah Schulman (also a co-founder of the Avengers!) Let the Record Show which covers ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, a direct action group, from 1987-1993 and is mostly made up of interview snippets from the Oral History Project. Schulman spoke to INTO by phone shortly after the book was released.

One of the things in the book that struck me was Rick Loftus, an ACT UP member who later became a doctor, talking about a pharmaceutical company cutting off a drug trial for people with AIDS. He said to the company, “if you don’t come in for this meeting, a bunch of green-haired weirdos from ACT UP are going to be screaming outside your office.” And people from the company actually did come to that meeting with the respectable, calm guy and they did work out a resolution. I’m wondering if you see a resurgence in organizations using both of these approaches together, the “inside” nice approach, but also the “outside” confrontational approach.

In the movement that I’m in, The Palestine Solidarity Movement, that is not the case.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

They’re not on the inside.

I mean, there are all kinds of levels. Like, Rashida Tlaib is a congresswoman, so she is on the inside. But she’s not acting like an insider. She’s going to the floor and speaking about her position on Palestine. I don’t think anyone in Congress thinks she’s an insider.

Do you think it’s harder to do that kind of inside/outside approach now with the increase in police violence?

Well, we didn’t sit down and say, “Let’s do inside /outside.” ACT UP never theorized itself.

You also quote some folks from ACT UP who were strongly against some official ACT UP demonstrations and tactics. And I’m wondering if you were against some of them or didn’t think they were effective.

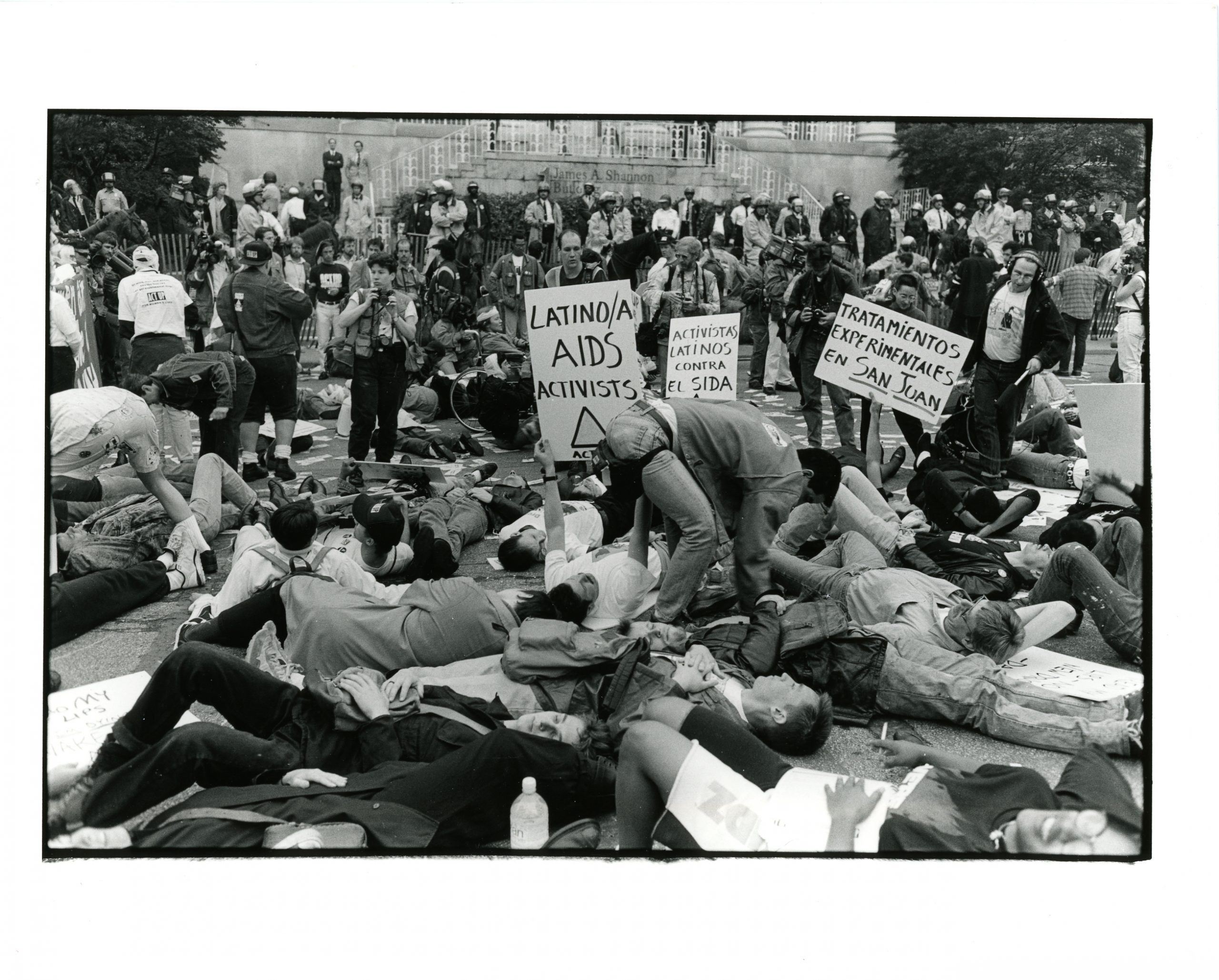

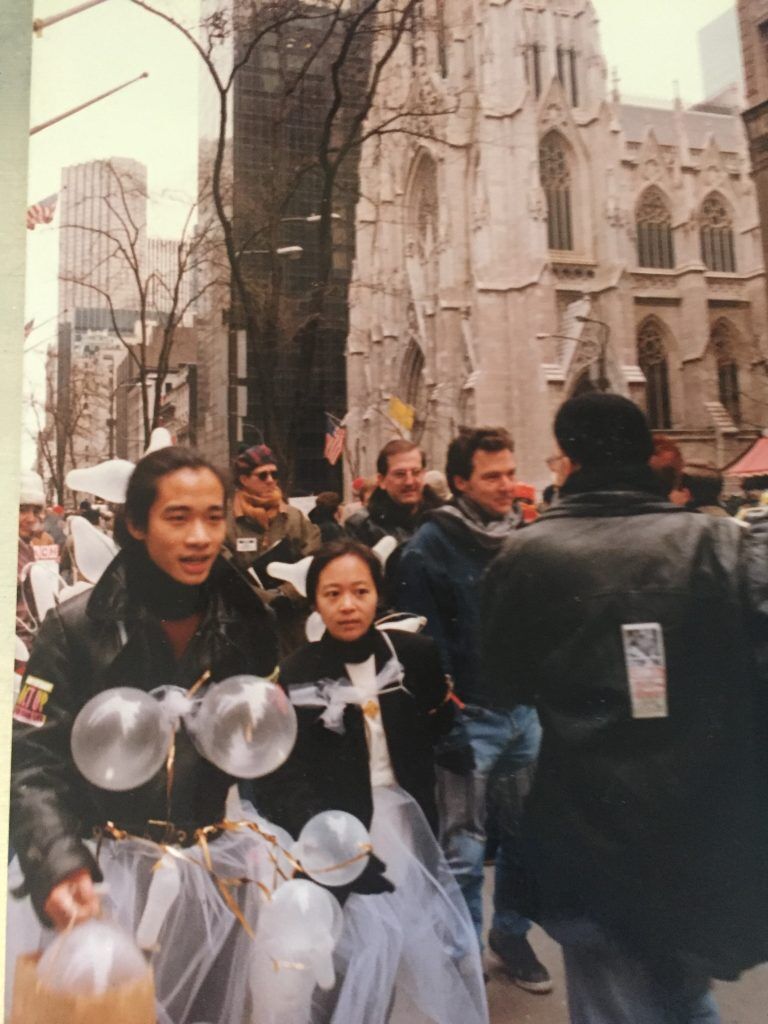

When the organization had decided to do a silent die-in at St. Patrick’s Cathedral during mass, some Protestants were concerned about ACT UP being perceived as an anti-Catholic organization. I don’t think the Catholics and Jews in ACT UP cared about that. The decision was to do a silent die-in inside the church. And so I went there to do that. Then Michael Petrelis jumped on his pew and started screaming at the cardinal. “Stop it, stop it. You’re killing us! Stop it.” And pandemonium broke loose. People started screaming and throwing flyers and there were police. I was upset because I thought that it had gone against what we had agreed, but I was wrong. And it’s okay to be wrong. Afterward, there was a post-action meeting at ACT UP and some people were angry at Michael for going against what people had decided, but some people felt that he turned it into a great action. When I later interviewed Michael, I asked him why he did that, and he said that nobody in ACT UP would let him into their (smaller) affinity group and he was angry. It was not respectability politics.

I heard the book has been optioned as a TV series. Congratulations.

Thank you.

But in the book, you point out how rightly pissed off Robert Vasquez-Pacheco and Moisés Agosto-Rosario were when Pose had this corporate representation of ACT UP.

They were mad that Pose had fictional people of color at the ACT UP action while excluding people of color who were actually in ACT UP.

I’m wondering if that might have made you hesitant about a TV adaptation of your book.

The person who optioned it was in ACT UP, Christine Vachon, (who produced Carol and the much anticipated Zola). Not only was she in ACT UP, her partner, Marlene McCarty was the only woman in (ACT UP-affiliated art group) Gran Fury. I couldn’t ask for better than that.

I think most people who are interviewing me and who are reviewing the book have not read the book. They’ve read the introduction.

I remember at Outwrite, the Queer Writers Conference during the early ’90s, you wondered out loud on a panel if there would ever be a political assassination that happened because of the government’s disastrous handling of the AIDS crisis. That didn’t happen, but I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who thought a lot about that question during the Trump administration, because of the many terrible things they did. I’m wondering if you have a theory on why our side is really never the one shooting politicians or anybody else?

The question that I asked and it’s in my book, People in Trouble, was: in a movement of people who knew they were going to die and yet at that point and thereafter never committed an act of violence, why not? I think the answer is: being violent is a dominant position. In those days straight people used to come into the Village to beat up gay men as entertainment. But queer people never beat up straight people. ACT UP never committed an act of violence. Violence was committed against ACT UP members: police beat up Chris Hennelly and left him with a permanent brain injury. ACT UP never passed a resolution saying it was a non-violent organization. It always kept that option open. But they never committed an act of violence.

In a movement of people who knew they were going to die, and yet at that point and thereafter never committed an act of violence, why not?

You let the words and actions of some of the privileged white gay men who broke off into Treatment Action Group from ACT UP expose them as misogynists. During the Zoom interview for the book you did with Alexander Chee, at the 92nd Street Y, former ACT UP members Linda Meredith and Peter Staley were having a huge disagreement in the comments, just like the old days. I’m wondering, do you think any of these guys have redeemed themselves since?

Of course. A number of people that I interviewed, like David Barr and Mark Harrington, said that they felt that they had been too arrogant.

Do you think that’s been reflected in their actions?

Well, these people have done a lot of work since that time. The organization Peter Staley is part of, PrEP4All, is trying to get the COVID vaccine distributed internationally, which is incredibly important. And their plan was just endorsed by The New York Times.

In the conclusion of the book, you write about the illness you’ve been struggling with in recent years. You thank a whole network of people who took care of you, which is like the groups that formed around very sick people during the AIDS crisis: never blood family, but one friend would come in for some time and another friend would come in for another. I’m wondering if that memory was the model for arranging your own care.

It’s possible, but it could be that’s how I’ve done everything in my life. I’m always trying to do my part in the community, and the community does its part for me.

I’m going to ask you the question that you ask everybody in your interviews. What do you think ACT UP’s greatest achievement was?

It was changing the CDC definition so that women could get benefits and enter experimental drug trials. Every woman with HIV today who takes the medication is taking a medication that was tested on women because ACT UP opened up those trials.

I’m always trying to do my part in the community, and the community does its part for me.

Do you think ACT UP had a “greatest mistake”?

I agree with Garance Franke-Ruta’s assessment of why ACT UP fell apart. The stakes were very real. There was a lot of pressure when we couldn’t get action or change in the timetable that we wanted and needed. I don’t really blame the people in ACT UP for ACT UP’s demise [note: ACT UP New York still meets, on Zoom these days, but its membership is not nearly as large as it once was]. I think it’s amazing that ACT UP did what it did.

Is there something about ACT UP that during the course of all these interviews, over nearly twenty years, surprised you?

Almost everyone in ACT UP was myopic and no one had a full sense of what was going on. So as Jim (Hubbard, the co-director, of the ACT UP Oral History Project) and I over the years accrued more and more knowledge, it came to a point where we were the only people who had an overview. That’s one of the reasons that there had to be a book. That was my biggest surprise.

Is there anything else that you want to say that I left out?

Well, I think there are some important scoops in the book. In the Dr. Joseph Sonnabend chapter, he gets the Freedom of Information Act papers on the Burroughs Wellcome AZT (for years the only medication to treat people with HIV) trial and finds out that the trial was corrupt. And I think someone needs to hold the people from Burroughs Wellcome accountable for that, because many people died from the side effects of AZT: it was also the largest profit-making pharmaceutical in the history of the world.

On the trial in which pregnant women with HIV were given AZT, I know that Peter Staley has information to show that the children who were given the drug while they were in the uterus were followed to age four. I don’t think that’s long enough.

Many people died from the side effects of AZT: it was also the largest profit-making pharmaceutical in the history of the world.

I completely broke down, in a whole chapter, how ACT UP raised money and where ACT UP got their money. And nobody has mentioned it. And how most of ACT UP’s lawyers were queer women who did thousands and thousands of cases pro bono. And then, of course how ACT UP’s Housing Committee was helping Haitian people get housing in New York so they could get out of Guantánamo, where they were being held because they were HIV-positive.

I think most people who are interviewing me and who are reviewing the book have not read the book. They’ve read the introduction. You tell me, as someone who’s read the book: why are all these substantive areas not the focus of the questions and the same questions in interviews repeated over and over?

I shouldn’t say I can’t fault people, but people are drawn to the familiar and those who are freelancers are not getting paid a lot for this. You can’t say they got all this money or have all this support.

But all the AIDS reporting that we did when The New York Times didn’t cover the AIDS crisis, nobody got paid for any of that.

That goes back to another question. What I miss about that time, when I went to ACT UP demonstrations and was in Queer Nation–which had a lot of similarities to ACT UP–was the chance for us to care for each other, to look out for each other in a way I don’t think the queer community has had an opportunity to do since then. Do you see examples of queer people taking care of each other these days?

I do. I’m lucky. I see people helping each other emotionally and helping each other financially and trying to help each other get places to live. They bring each other food.

Do you see that through mutual aid or through some other organization now?

No, just through relationships.

One of the things that you point out in the book was the nonprofit vs activism conflict. Like a lot of people, I went into nonprofit services for people with AIDS after I had been an activist and it winnowed down the stakes for all of us. You’re just thinking about how you are going to get funded as opposed to, “How can we redirect this disaster? How can we save people’s lives?” The future care queer people can give each other needs to also exist outside of the nonprofit world.

Right. That’s true for the whole society. ♦