Shu Lea Cheang’s Fresh Kill, a self-described “eco-noia” film, is extremely confusing down to its roots– but that makes it one of the more modern films I’ve ever seen, despite premiering in 1994. In a sense, it doesn’t want you to understand. It’s a movie that’s a little bit better than any audience could have been in 1992. It’s a movie about the future that feels like it actually comes from that future: a rare thing indeed.

Lesbian couple Shareen (Sarita Choudhury) and Claire (Erin McMurtry) are raising their daughter Honey on Staten Island, near the Fresh Kills landfill, a dumping ground which, shortly after its creation in the 50s, rose to prominence as the world’s largest landfill. In the 1980s, things got decidedly more toxic after Fresh Kills became the only dumping ground to accept the waste from the city’s other boroughs. This radioactive atmosphere is communicated through the magenta haze that sits at the top of the screen, like the faded windows of old cars, threatening to color the entire landscape neon. Which basically is what ends up happening: when Claire’s workplace, a Manhattan sushi restaurant favored by the Wall Street crowd, keeps seeking out a certain breed of fish for the aesthetic (“fish lips” are the new, hot thing on the menu) they eventually get a shipment that’s contaminated by a mysterious substance that turns the eaters bright green. Honey ends up ingesting some of the fish and goes missing, along with several area cats, who get their radioactive glow from a shady brand of cat food known as “Sea Wonder.”

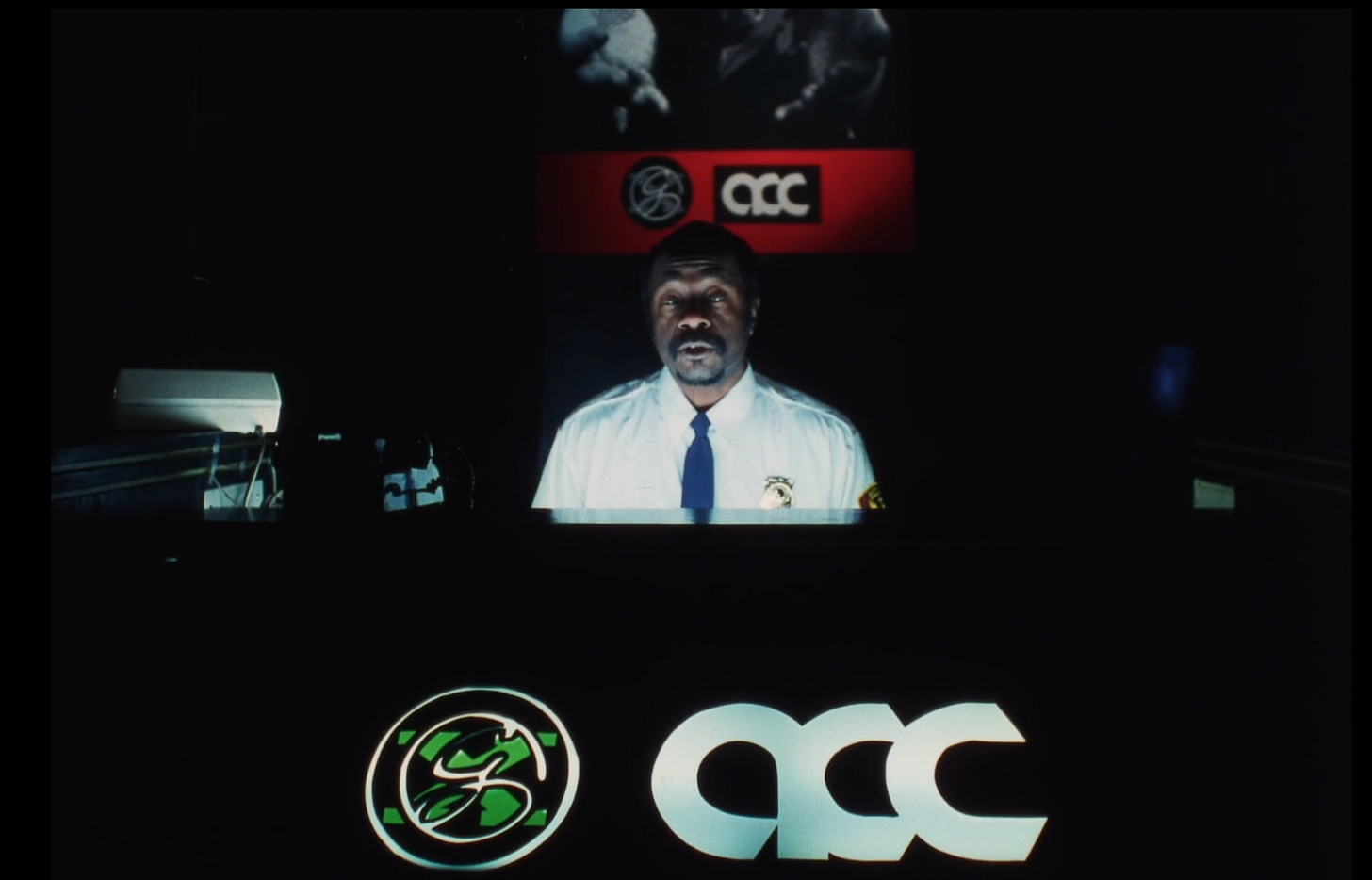

That’s essentially as far as the plot goes: the women—who enjoy f*cking while playing the accordion—try to find out the mystery behind what Honey terms the “green glee” that’s been overtaking everyone, turning their speech into incoherent blank verse. But to be honest, even before that they were hard to understand. This movie is a true collagist affair: fake infomercials, nonsensical conversations, and random dial-up Internet warnings show up onscreen with very little to connect them. It’s a challenge to watch, but after awhile, you get what’s happening. It’s the same thing that’s been happening to us for a long time– we’ve just been trying not to deal with it.

In my day to day life, I think little about climate change. This, as the author Maggie Nelson points out in her book “Freedom,” is a “structural feature” of the climate crisis: the fact that it is too big, and too unmanageable in its impact, to be comprehended in a meaningful way by the civilians who must deal with its inevitable consequences. For so long, it’s been the elephant in the room, and we think about it in the same way a lot of people tend to think about death: sure, it’s inevitable, it’s coming, but why think about it? It’s so morbid.

Related:

The Audacity of Writing From the Margins

Indigenous writers are already doing more than enough compromise by writing in English a language that has been imposed on us.

Since the 90s, lesbian feminists have been arguing for a better world. Read any piece of lesbian lit from that, or any “Dykes to Watch Out For” strip from 1988 to 2005, and you’ll be shocked by how modern it is. Because the queer community has, for so long, been the community that’s had to deal with it. But, like the Cassandra figures we often are, we haven’t been listened to. And now, everyone’s essentially glowing green, and we can’t say we weren’t told.

I watched this movie in tandem with the paranoid masterpieces included in Criterion’s 80s horror collection, and it made me realize something. Most horror movies of necessity take place in the suburbs, in an empty town, an abandoned house of the “no one can hear you scream” variety. It’s because you assume that in a city, a killer can’t remain incognito for long. There are assumed forces of law and order in a city that are missing from more traditional horror spheres: consider “Misery,” in which the one local cop, even though he’s good enough at his job to unravel the mystery at the center of the story, isn’t quite smart enough not to end up another casualty of the killer himself. There’s a haplessness about the idea of local law enforcement, a sense that even if it exists, it’s not actually effective.

The horror movies that take place in big cities are all of the Monster variety. A creature is attacking the city, and we have to stop it. In a movie like Fresh Kill, this logic still applies: the “monster” simply doesn’t have one face. It has millions. Our complicity is the problem, along with the structures that have been put in place to make sure some breathe toxic air and others don’t.

It’s a different kind of horror, but just as effective as the other kind, if not more chilling: everyone can hear you scream, they just don’t care.

Fresh Kill understands this in a nuanced way, even if the bluntness of its aesthetic doesn’t feel especially nuanced. The film picks up on the corporate nihilism that would come to define early Twitter: the moment at which brands realized that if they give themselves a human voice, they might be able to walk among us in comfortable disguise. Infomercials, the Internet, the understanding of trash economics—by which people like Shareen, Claire and Honey have to live atop a literal heap of garbage while someone like Tony Soprano makes millions off that same refuse—it’s all there. Which means one of two things: either this film could tell the future, or things have stayed remarkably the same, culturally, since that time.

I suppose the reality is a bit of both. We’ve been in crisis for so long, and we’ve been ignoring it for just as long. Culturally, it doesn’t benefit anyone to really think about climate change. It doesn’t make people spend money and it doesn’t make people participate in the travel economy, and it’s posed, often, as a direct threat to the current task of healing inflation. It doesn’t make for especially good (or entertaining) art either, which is perhaps the worst of it. But if we really chose to reckon with climate change narratively, what would it look like? Not this film, with its canny grasp of things. It would look more like the dismal Gus Van Sant film Promised Land, in which the concept of fracking exists merely to foist a kind of emotional growth upon Matt Damon once he sees the error of his ways. The truth is there aren’t many eco-dramas out there, and even fewer of them can be called good.

A movie like Fresh Kill is a time capsule: it reminds you not just of what things were like before the point of no return in regards to climate change, the time when people thought we could do something about it. Even more depressingly, it reminds you of what things were like when people made movies like this. When even Gus Van Sant was capable of making great art, narratively unfocused but at least halfway interested in the realities of queer peoples’ lives. It was a different world: a moment in which we had a choice to make as a country. We could become those upwardly-mobile yuppies desperately chasing trends, or we could be people who cared: unstylishly, nerdily, unfashionably. I don’t have to tell you what we ended up choosing.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox