Have you ever been grateful to a film for existing? That’s how I feel about just about everything Desiree Akhavan has ever done, from her ingenious series “The Slope”, co-created with ex-girlfriend Ingrid Jungermann, to her 2018 series “The Bisexual” and everything in between. 2014’s Appropriate Behavior (streaming on Criterion Channel, along with Akhavan’s 2020 feature The Miseducation of Cameron Post) is perhaps the work that sits the most squarely in between those two accomplishments, and uncoincidentally, in between-ness is its core subject.

Appropriate Behavior is the story of a breakup, quite clearly the one Akhavan went through with Jungermann herself, fictionalized here as Maxine (Rebecca Henderson.) Shirin (Akhavan) is a late-millennial Brooklyn bisexual leaving the lesbian relationship that consumed most of her 20s. She is understandably salty about this, even though at least part of the breakup is due to Shirin’s own inability to come out to her Iranian parents, telling them—during a flashback visit to her and her girlfriend’s new apartment—that they’re sharing a bed because it’s cost-effective and “European.”

The film opens on that most familiar of scenes, the lesbian breakup. Who’s going to get what, and what needs to be thrown out? Shirin is packing away her stuff in boxes when Maxine reminds her of a small shoebox on the bed. “Don’t forget this,” she says without looking up from her phone. “It was a gift for you,” Shirin says, hurt. She takes it anyway, and while walking away from the apartment she up until recently called home, she almost throws it out, resting it open-faced on a pre-existing pile of trash. It’s a harness with a huge silicone dildo attached. She takes another look at it before rescuing it from the heap: it may have a life after the breakup after all.

It’s scenes like this—moments like this—that make Akhavan feel so vital as a queer filmmaker, especially right now.

I guess it’s that it’s really hard to capture a moment on film, even though it looks like the easiest thing in the world. Akhavan’s work has always felt to me extremely of the moment and also ancient: she understands queerness in a historical way. I don’t mean to suggest by this that her work is somehow bogged down with reference and citation. It’s more that she understands the sadness that came before in a way that’s weirdly absent in so many other queer works of art.

In her 2016 TV show “The Bisexual,” there’s a line that sticks out. Akhavan’s character Leila is explaining to a younger woman (who identifies as queer, not bisexual) why being gay is different for her.

“I think it’s different. I think when you have to fight for it, being gay can become the biggest part of you.”

It can, and it does, and the thing that creates a wedge between people closer to my age and Akhavan’s and the younger generation is that sense of the Internet having made things easy, or at any rate easier. We’re resentful of that, because we don’t understand it. How could we? We grew up in a different world.

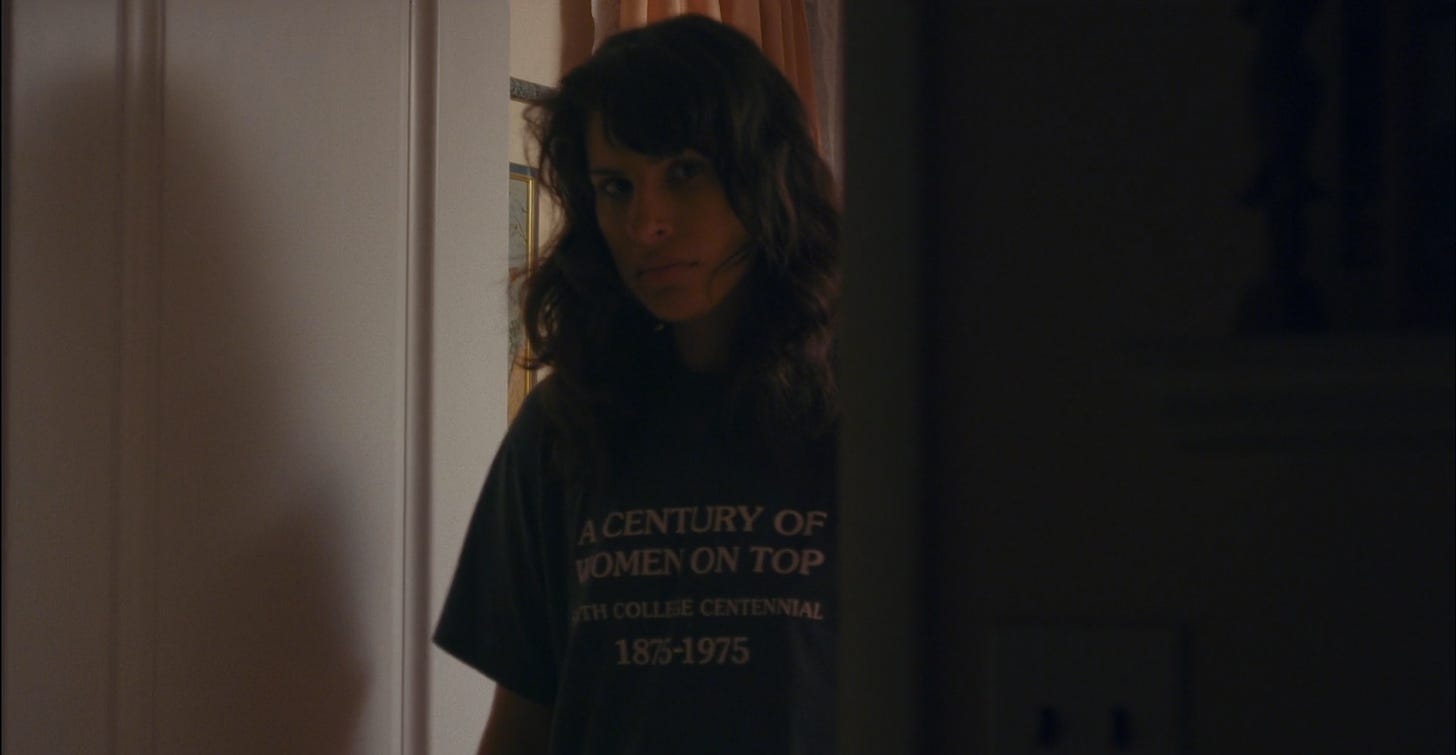

It’s not that I resent current shows and films for making queerness seem like a neverending party where everyone is hot and cool and wearing a graphic tee from Wildfang. Although—what am I saying, that’s absolutely true. I am resentful. I am an old queer who remembers at least a piece of what it was like in the days before. When it was hard. And it’s still hard, but I think we’ve really lost something by acting like it’s supposed to be easy. The point of movies like Appropriate Behavior is that you have to fight for this life. You have to fight against yourself and your world and your family and your community just to clear through the fog of straight propaganda. You have to do such heavy lifting just to define yourself. And then you go out into the world, in search of the community that you’ve fought so hard to be a part of, and what’s waiting for you there is the same thing that’s always been waiting there, for you or any other baby queer. Loneliness. Awkwardness. A feeling of being the wrong kind of gay, or the wrong kind of trans person, or having come late to the party, or being ill-equipped to handle the party itself, with its closeness and bodies and heat and noise.

Akhavan’s work understands what it is to be in-between, in every sense. She can’t fit in with her conservative Iranian family, and she can’t fit in with her more militant queer girlfriend, and she can’t fit in—being bisexual, or as she calls it here “a little bit gay”—to the queer community of 2014 Brooklyn, where being bisexual is at worst a betrayal, and at best horribly uncool.

We like to think that we leave high school and all its petty concerns behind as adults, but I’ve honestly never felt, entering a queer space, any kind of beautiful embrace. I’ve felt like the uncool kid in the cafeteria, where everybody has already found people to sit with and I’m just standing there deject with my butterscotch-colored tray of sludge. I’ve never felt anything but sadness and embarrassment because I’ll never be a cool queer. I’ll never be a hot queer. I’ll always be the person who reads a book at the party, or locks themselves in the bathroom just to get away from the aggressive pain of seeing other people have the good time that I’m incapable of having.

Some shows try to show this aspect, but they fail: “Work in Progress” is one, a show that started promisingly as the story of Abby, an aging butch lesbian who’s prepared to kill herself if things don’t change in her life in 90 days. Suffice it to say: things do change, in really unrealistic and silly ways. We’re not allowed to sit with Abby in her loneliness or even stay with her in the aging process. Instead, she’s constantly going out to parties and dating hot baby queers and acting like she’s younger than she is.

I wonder sometimes if it’s a fatal flaw of cinematic storytelling itself that we can’t just show loneliness onscreen. We can, but it usually translates as melodrama, and that’s not always the truth of it. One of my favorite shows of this year so far, Bridget Everett’s “Somebody Somewhere,” gets close to showing the truth of queer pain, oddly enough through its straight protagonist, Sam. We meet her as her lonely period is about to come to a close, courtesy of a newfound queer community that’s been hidden in plain sight in her hometown of Manhattan, Kansas. We see the change in her after she’s invited to an open mic night by her gay work friend. They sing the Peter Gabriel/Kate Bush duet “Don’t Give Up,” and something breaks in Sam, just as it breaks in us. “I changed my face, I changed my name,” she sings, “but no one wants you when you lose.” The song’s original video consists of a camera moving in on a long hug between Bush and Gabriel, making the lyrical meaning of the song concrete. Community can feel like a long hug, like security. It can also feel like you’re freefalling with no one to catch you.

At work, I feel loneliness. With my family, I feel loneliness. With all but a few close friends, I feel loneliness. In a very real sense, loneliness is part of my life and my nature. Maybe queerness is part of that, maybe it isn’t. I think it’s like this for a lot of people, but you’d never know it, because we view loneliness as a personal failure. An inability to connect, rather than an admission that sometimes, there’s not a whole lot to connect to.

This is a problem I keep butting up against in my attempts to make a show, or movie of my own, where the question I keep coming back to is, “how do you show a life that doesn’t really involve a lot of other people?”

How do you show loneliness except by contrast? How do you film a loneliness that does not exist to be solved?

I don’t know. But I’m grateful to this film, at least, for trying. For coming close.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox