India’s gay prince knew the country was poised to take a great leap forward on LGBTQ rights. He saw that energy in a crowded lecture hall six months ago.

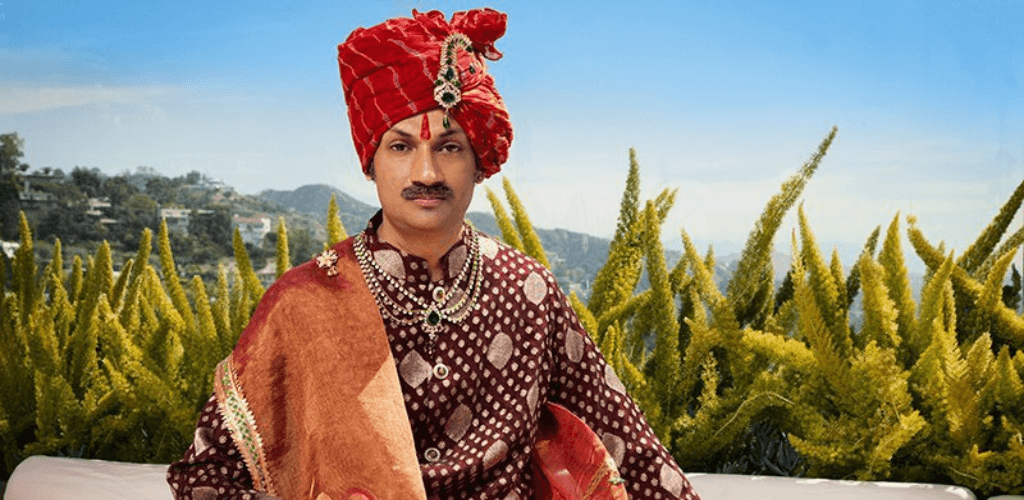

Manvendra Singh Gohil, the world’s first openly gay royal, was invited to speak at Karnavati University in the western state of Gujarat. Attendance was not mandatory for students, he said. Ahead of the India Supreme Court’s ruling on its century-old sodomy law, the event was open to those who “wanted to understand the legal issues [around] decriminalizing the homosexual act.”

The hall was designed to hold 500 students. Gohil claimed it was standing-room only.

“Some [students] were sitting on the steps,” Gohil told INTO over the phone, noting that the turnout far exceeded the college’s modest expectations. “It was absolutely packed. There was no place in the hall at all.”

But it wasn’t just young people who crowded in the aisles and huddled in the back of the room to hear Gohil’s speech this March. Despite the fact that the presentation was intended for law students, he claimed that faculty came to hear him speak — as did the dean and vice chancellor of the university.

The Q&A portion of his talk, normally a muted affair for typical guest lecturers, lasted for more than 45 minutes. The lively discussion eventually had to be cut off by the university because of time constraints.

Those conversations were reflected in a groundbreaking ruling from India’s top court on Thursday, when a five-judge panel unanimously ruled that colonial laws criminalizing homosexuality are unconstitutional. Chief Justice Dipak Misra claimed Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code — an unfortunate holdover from British occupation — is “irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary.”

“Any consensual sexual relationship between two consenting adults — homosexuals, heterosexuals, or lesbians — cannot be said to be unconstitutional,” Misra said as he read from his written ruling at 10:40 a.m., with the eyes of the world watching.

The decision had been a long time coming.

Section 377, which prohibits intercourse “against the order of nature,” was first struck down by a Delhi High Court in 2009. The Supreme Court, however, overturned the historic ruling just four years later. Petitioners immediately appealed to reverse the 2013 ruling, one the nation’s highest bench later admitted was a “mess.”

In conversation with INTO on Sunday, Gohil predicted the repeal of Section 377 would be monumental for India’s LGBTQ community.

Under the law, queer and trans people faced up to life imprisonment if prosecuted for what the penal code termed “unnatural offenses.” But as in the case of Russia’s anti-gay propaganda law, Gohil explained the vagueness of that phrase led to the law being “misused” as a carte blanche for harassment and persecution.

“Police have been harassing us for distributing condoms,” he claimed. “Police have been arresting our people.”

While the end of Section 377 is a major step forward for LGBTQ rights in India, Gohil recognizes the country has a lot more work to do before sexual and gender minorities are fully equal in society.

While a Times of India survey from earlier this year showed a majority of Indians supported repealing the sodomy laws, a 2015 poll from Ipsos found that just 29 percent of respondents were in favor of legalizing same-sex unions. Support for marriage equality in India was the fifth-lowest among the 23 nations surveyed.

Earlier this year, Amnesty International reported there had been an “alarming increase” in hate crimes against marginalized groups. Around 100 bias attacks were reported in the first six months of this year. Along with religious minorities and individuals among the lower castes, India’s hijra — a term encompassing eunuchs, intersex, and trans people — were among the most likely groups to be targeted.

Gohil believes further progress will come by educating those outside the community on LGBTQ lives.

“The more allies we get, the more we will be able to [gain] acceptance,” he said. “That is what I call mainstreaming. The only way you can mainstream your issues is to get support from the people who are not in the community and that is the allies. And then you can expect social change to happen.”

Embarking on a public education campaign in India is no easy task. Owing to the hundreds of languages spoken by its 1.2 billion residents, the country has often been deemed “ungovernable.”

But as India’s most visible queer person, Gohil is used to a challenge.

Following the outpouring of support for his March speech, Karnavati University invited him back to launch the nation’s first-ever LGBTQ module. Divided into five days, the 20-hour course covered topics related legal, social, and historical issues — including mental health and HIV/AIDS.

More than 200 students signed up for the non-compulsory course. Although Gohil expected religious conservatives would protest the module, it was met with extremely little outcry.

Other professors even sat in to listen and ask questions, Gohil claimed. Many are themselves “ignorant about this subject,” he said.

But in addition to its stated mission of educating allies about the struggles faced by LGBTQ people in India, the class — which was spearheaded by Gohil’s personal charity, the Lakshya Trust — offered queer and trans youth the rare opportunity to be seen. Gohil claimed one student came out to his peers as a trans man during class discussion.

The module concluded on Aug. 31 with an exam handed out to students. But given its warm reception, Gohil hopes to expand the LGBTQ course to other universities — maybe even spin it off into a semester-long class.

Gohil knows firsthand the importance of continuing this education. After becoming one of the first national figures to come out as gay in 2006, the likely heir of the Maharaja in Gujarat was disowned by his parents and sister. They claimed the prince, then 41, had brought “dishonor” to the family.

The prince believes when classrooms don’t address the LGBTQ community — whether in sexual education curricula or history textbooks — it creates more stigma in families and communities.

When silence is the norm, people “get the wrong information.”

“Parents are not accepting their children, most of them,” he claimed. “They usually blackmail their children or send them into marriage with the opposite sex. If these children are now educated, they will be better parents, even if their children are gay or lesbian.”

Gohil predicted that the repeal of Section 377 would be “the beginning of a new chapter for a new fight” in India, one that could last decades.

“It will take a long time for society to come to terms with our sexuality,” he said.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox