Early in the film Colette, the titular character (Keira Knightley) has once again been left alone at a party by her husband, Willy (Dominic West). She’s drawn into conversation with the mustachioed Gaston de Caillavet (Jake Graf), who reads her palm. Just as Colette and de Caillavet begin a tête-à-tête, a jealous Willy interrupts and sweeps his wife away. Willy is successful in his intervention, and Gaston de Caillavet — and, thus, Jake Graf — is never seen again in the movie.

The casting of Graf, a transgender man, as de Caillavet, a cisgender historical figure, has led a few article headlines to praise Colette for having forward-thinking casting. They’ve also praised the inclusion of Rebecca Root, a transgender woman, as the writer Rachilde, but in her blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo, she could have just as easily been named “Party-goer 3.” That said, the movie benefited from their presences. Graf was charming in his brief role, and Root participated in a beautiful shot.

The positive inclusion, however, does little to mitigate Colette’s larger casting problem — Colette’s long-time lover, a transgender person named Max de Morny, was played by cisgender actor Denise Gough.

The practice of casting cisgender actors in transgender roles is an enormous problem and the reasons why are well-trod territory. Max de Morny is certainly transgender, even if the exact specifics of his identity are difficult to determine.

In Colette’s portrait of de Morny in her book, The Pure and the Impure, she uses feminine words for her lover, but calls him “an androgynous creature” who struggles between identifying with women or men. She adds that de Morny “blush[ed] with joy and gratitude” when a cisgender man called him “Father.” It sounds like a possible moment of gender euphoria, when transgender people feel joy at having their gender recognized.

It should be noted that Colette is not a trustworthy source, as her “non-fiction” often had a loose relationship with facts. In her profile of de Morny, she portrays herself as a neutral observer and completely omits that she and de Morny were once lovers for many years.

Regardless, it is factual that de Morny dressed as a man, lived as a man, and referred to himself with the name Max. Colette’s profile of him does not dispute that. Even if it casts doubt on whether de Morny identified explicitly as a man, it portrays him as struggling with the cisgender binary and possibly identifying with a non-binary gender. However, if he’s not a man, that doesn’t mean he’s not trans: Non-binary people and gender questioning people are both transgender identities. (I will continue to refer to de Morny with male pronouns for the purpose of this article, based on the fact that he lived as a man.)

However, many historians struggled to accept de Morny’s transness. Colette biographer Judith Thurman initially calls Max de Morny a “lesbian transvestite” and relentlessly refers to him with female pronouns even though she later says it’s not clear if de Morny identified as “a lesbian or a man.” Historians often refer to de Morny and Colette as having a lesbian relationship and call their famous kiss as part of a Moulin Rouge show a “lesbian kiss.”

Because most historians brand de Morny a woman, I was aware that Colette might do the same. That would have been unacceptable, but it would explain the casting of Gough.

However, Colette embraces the same kind of gender complexity Colette portrays in The Pure and Impure. The film reveals most of the details about de Morny’s gender in conversations Colette has with other characters, such as where he was first described as a woman in men’s clothes. After Colette and de Morny become lovers, she and Willy (who have a selectively-open marriage) muse about de Morny’s androgyny and the lack of appropriately gender-neutral language for him. Willy later flippantly refers to de Morny as a “lady man,” which Colette protests. In the last of these conversations, Colette corrects Willy’s language and insists he use male pronouns for de Morny. That brief scene was the only definitive stance taken on de Morny’s gender in the whole film.

There’s only one scene where de Morny hints at his own gender: While telling a story about himself during his former marriage, he confusingly refers to his past self as a woman. However, in the same conversation, he also says something to the effect of, “What would being in a relationship with me say about my husband?” implying that a man in a relationship with him would be queer. It could be interpreted that de Morny is saying he’s a man, but it’s not clear.

The film’s version of de Morny’s exact gender identity is unclear, but like the real person, the character certainly has some type of transgender identity. If that’s the case, then why was a trans actor not cast? This casting department specifically sought out Graf for a bit part— why did they not put in the same effort to find a trans actor for de Morny?

Graf and Root’s conversations with the press have revealed one strange anecdote about the casting process: Root was invited to audition for de Morny. As discussed above, de Morny was possibly a trans man, a non-binary person, and/or a gender questioning person. The one type of trans person he was definitely not was a trans woman. Root’s anecdote reveals that the casting department sought women to play de Morny. (In addition, the historical figure Root briefly played, Rachilde, was also possibly trans masculine.)

I can’t help but ask: Why wasn’t Graf cast as de Morny? Graf was the only actor in the film whose gender history was similar to de Morny’s.

It’s one thing to praise the casting for having Graf and Root play “cisgender” characters (if, indeed, Rachilde was cisgender). But de Morny was a significant character in the film. By my count, Gough appeared in nine scenes. Graf appeared in one scene and had about four lines. Gough had over twice as many scenes as Graf had lines.

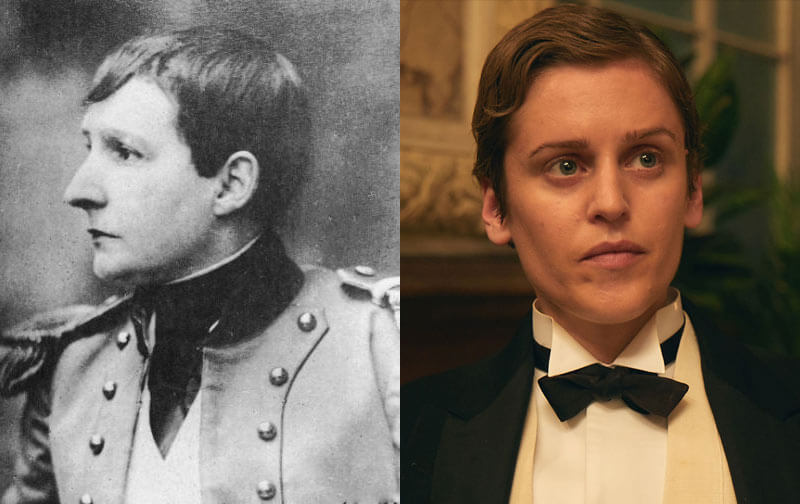

One could argue that Graf could not play de Morny because they don’t look similar. That’s true — de Morny was fat and Graf is not. Fat erasure is real and my preference would be for a fat actor to play him. However, Gough — slim, blond, and far from passing for a cis man — doesn’t look like de Morny either. At the end of the film, a picture of de Morny with Colette is shown, and the expanse between Gough and de Morny’s appearances is laughable.

One could argue that de Morny should be played by a woman because he did not pass as a cisgender man. I’m not sure if that’s true. De Morny certainly seemed passable to me in the photos of him. Though the facts of his life indicate that the people around him perceived him as a woman — such as those who protested his kiss with Colette at the Moulin Rouge and the person who refused to sell a house to him because he was wearing men’s clothes — on the other hand, he was famous. De Morny came from a rich and titled family, he married a rich and titled man, and he sculpted and painted and wrote and threw fancy parties and famous writers put caricatures of him in their books. Everyone knew his business. It wouldn’t surprise me if he did pass for a cis man — at least sometimes — but he was probably not treated as one because his trans status was well-known.

Secondly, if the casting department was determined to cast someone who could have been perceived as possibly a woman by the viewer, there are trans men and non-binary people like that. Not all trans masculine people pass for cis as supremely as the mustachioed Graf and not all trans masculine people take testosterone.

Thirdly, not all effects of testosterone are permanent. While a lower voice isn’t going to go anywhere, after a few months of changing hormones, face shapes will change. There is a big difference between the angular testosterone face shape and the rounder estrogen face shape. While I’m sure some actors would be unable to go off testosterone for a part, the casting department can at least ask. There are trans actors willing to do things for a role that would ordinarily be associated with a gender they’re transitioning from, and to say otherwise is to gatekeep roles while pretending to be benevolent. Clearly Root, at least, had no problem auditioning for the role of a masculine person even though she’s a transgender woman.

I can’t help but be bothered by the idea that Colette is being praised for casting Graf in a cisgender role. That’s more of a fun fact than a milestone. Graf had a bit part and Gough was fourth-billed. To be candid, Graf’s casting seemed like a stunt meant to appease trans critics and distract them from the lead role that rightfully belonged to a trans person. Trans people aren’t allowed to play our own trans ancestors, our own trailblazers, when our stories are good enough for a top-billed role. Don’t throw us scraps and call it a meal.

This isn’t even the first time Graf and Root had a film together where they were both cast in parts presumed to be cisgender — that recognition goes to the 2015 Oscar-nominated The Danish Girl. You probably remember it because of the outrage over Eddie Redmayne’s casting as trans trailblazer Lili Elbe. Root and Graf — who also played tiny parts — were sent out to do damage control.

There’s a pessimistic part of me that wonders if Root and Graf’s performance with the press earned them their auditions for Colette. I don’t blame Graf or Root for praising Colette or standing up for The Danish Girl. More than anyone, they understand the futility of demanding trans casting for box office movies. I also understand an actor’s reticence to say that actors should only play parts exactly like themselves, especially if parts exactly like themselves aren’t being written. They’re doing their jobs, and I want them to have more jobs.

When Graf and Dominic West stared each other down across the giant screen, I was struck by how similar the two men looked. West’s garrulous turn as Willy dominates Colette and the film, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he had more lines than Keira Knightley. What a tremendous, meaty role — Willy is charming and harsh, a lover and a fighter, who gives his wife a house as a gift and then locks her in it until she writes for him. Willy is not a nice man, but it’s the kind of complex role that will make the Academy voters pay attention. I wonder what Graf would have done with the role.

Trans audiences won’t be placated with actors like us playing bit parts and cameos. If you’re going to take our Max de Mornys and our Lili Elbes, be prepared to give us something real: Give us the Willy roles and the Colette roles. If you’re going to profit off of our history, be prepared to give up something of equal value to trans actors.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox