CW//Suicide

To tell a convincing lie, you should believe it as you tell it, an adage Kristine Stolakis’s film Pray Away brings to mind. Her new documentary features contemporary interviews with the “ex-gay” leaders of anti-queer movements, including Exodus International’s John Paulk and Yvette Cantu Schneider. Most in the film, like Michael Bussee, a co-founder of Exodus who left the organization to be in a committed relationship with his male coworker (the couple discussed their story on talk shows, like Joan Rivers’, in the early ’90s) are now openly queer. INTO spoke with Stolakis by phone.

INTO: You’ve said your uncle, who underwent anti-queer, anti-trans conversion therapy, was your inspiration. Can you tell us about him?

Kristine Stolakis: My uncle came out as trans as a child and went through conversion therapy in the ’60s and ’70s, when all therapists were conversion therapists. What followed was a lifetime of mental health struggles including addiction and suicidal ideation. But he was one of the first people I loved and who loved me.

When I went to film school, he passed away. I decided my first feature documentary should be about conversion therapy. What surprised me is: the majority of conversion therapy organizations are run by ex-LGBTQ Christians. Before I had imagined straight, cis people headed these organizations. The leaders and spokespeople of the ex-gay movement helped me understand my uncle’s hope to change and his self-hatred when he didn’t.

INTO: Did your uncle ever talk to you about his experience?

KS: My uncle spoke to me about the loneliness he felt because he had made the choice–though you could debate what “choice” means here–to be celibate, a common “solution”. He shared with me the frustration of never being in a romantic relationship he felt was healthy. He had internalized that being LGBTQ was sick and sinful. He never shook that.

INTO: When you were talking to the ex ex-gays, did they have ground rules? Were there some questions they wouldn’t answer?

KS: There was nothing I couldn’t ask. The former leaders are reckoning with their past and were ready to speak their truth and try to right the record. The film does not shy away from the pain they caused, but they are victims themselves.

My uncle had internalized that being LGBTQ was sick and sinful. He never shook that.

INTO: Jeffrey McCall is the only person you talk to who is still involved in this work and who considers himself ex-gay and ex-trans. Was he wary of you because you are featuring ex-ex-gays in the film?

KS: I told him the film would include a lot of voices critical of the ex- LGBTQ movement. He agreed to be in the film anyway. He does not see what he’s doing as conversion therapy, and he believes he’s doing the right thing. A lot of people practice conversion therapy in secret. Jeffrey was willing to go on the record.

INTO: Were you careful about just how much of his anti-queer, anti-trans message you put in the film?

KS: Our approach with Jeffrey was to meet him where he was at. People with similar experiences might say they’re gender-fluid or don’t exist in the gender binary. That’s not the language he uses for himself. We didn’t challenge Jeffrey directly, but surrounded him with contradicting voices whose lives have a lot of parallels to his. Conversion therapy doesn’t work. Self-harm and suicide are common. If you go through conversion therapy, you are more than twice as likely to attempt suicide. Close to 700,000 people in the US have gone through conversion therapy. It continues on every continent–except Antarctica. The movement has conferences, books, famous ex-LGBTQ people and pseudo-psychologists who peddle disproven theories on why people are LGBTQ. They have podcasts, hashtags and Instagram feeds.

INTO: Julie Rodgers, who was brought into the movement at 15, describes being around supposedly ex-gay youth at the Exodus conferences–of all places–as like queer summer camp. We see that same camaraderie in the gatherings of ex-gay and ex-trans adults Jeffrey McCall organizes. Have you shown the film to him?

KS: We did show the film to Jeffrey.

Conversion therapy doesn’t work. Self-harm and suicide are common. If you go through conversion therapy, you are more than twice as likely to attempt suicide.

INTO: Did he see in those scenes what the rest of us do?

KS: What Jeffrey said about the film, he shared in private. You can look up what he’s saying about the film publicly.

INTO: Did anyone in the film talk about the hostility that they’ve encountered from the queer community because of their past anti-queer work?

KS: Each former leader has their own story of trying to reenter local LGBTQ+ communities. They’ve received a range of reactions, from people who will never forgive them to people who accept that they are trying to right their wrongs and every kind of reaction in between.

INTO: It sounds like you don’t doubt the sincerity of the people you talked to. Is that right?

KS: Some of the former leaders were in denial. This is the only profession some of them had ever had: being paid to be ex-LGBTQ. Every former leader I’ve spoken to wishes they’d left the movement earlier. These people, at first, thought they were helping. In right-wing Christian circles, homophobia and transphobia creates a breeding ground for new people to believe they can change and to try to show others a way out. But the only way out is to leave the movement and find a community that will love and accept you as you are. ♦

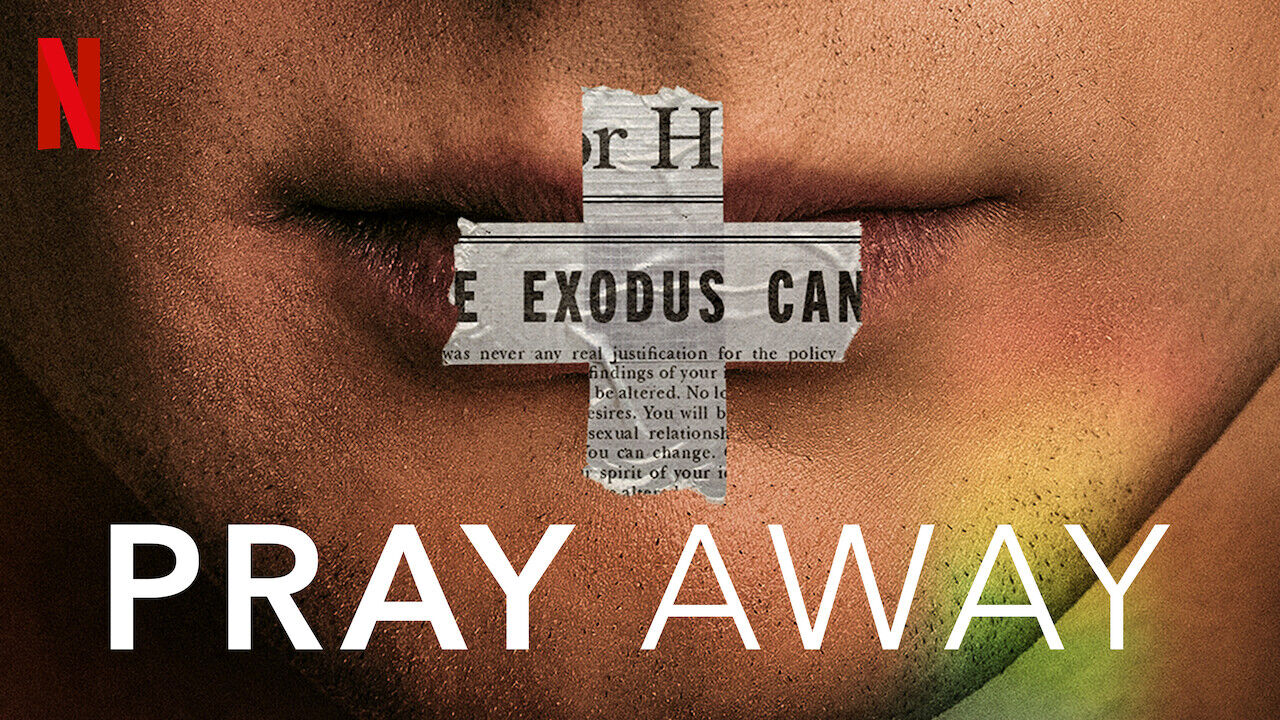

Pray Away premieres on Netflix today, August 3rd.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox