Why do we hold Pride parades?

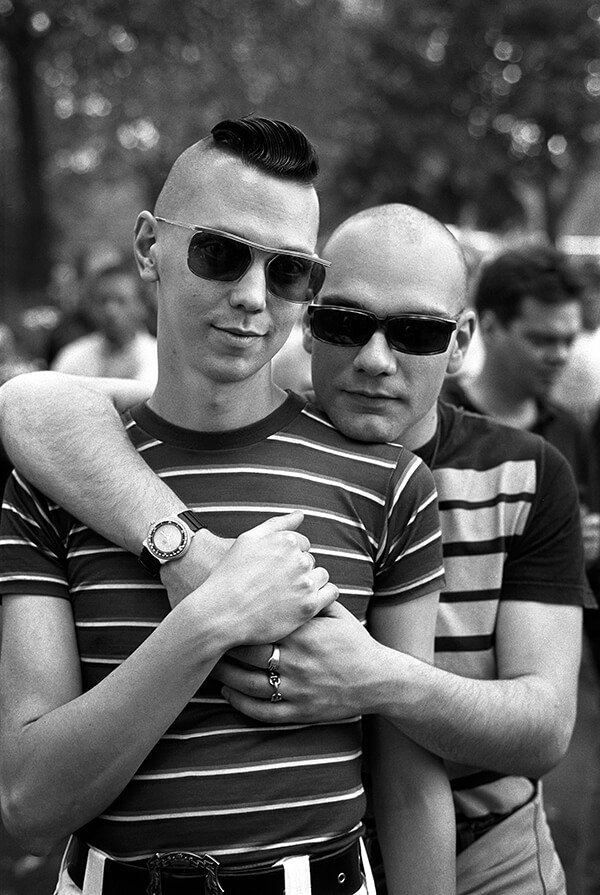

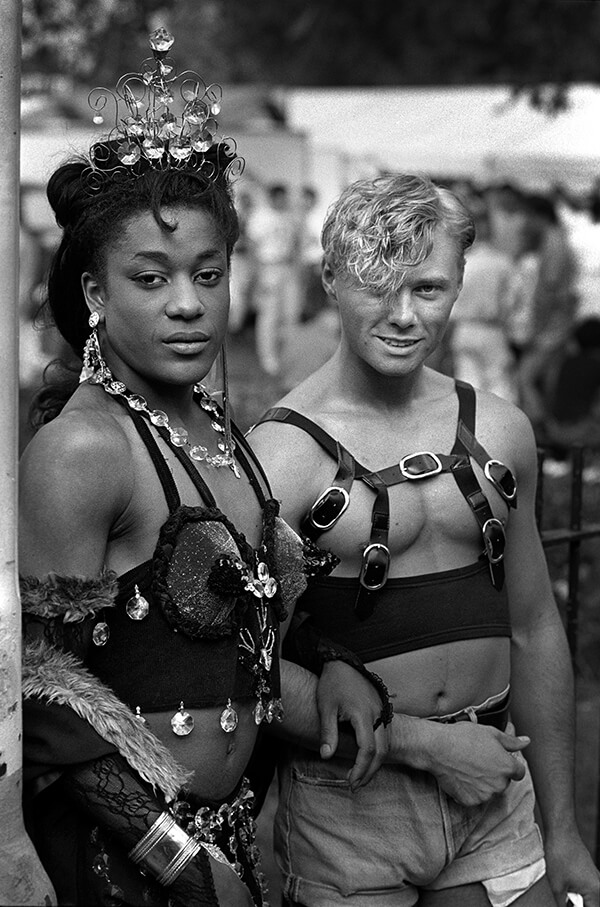

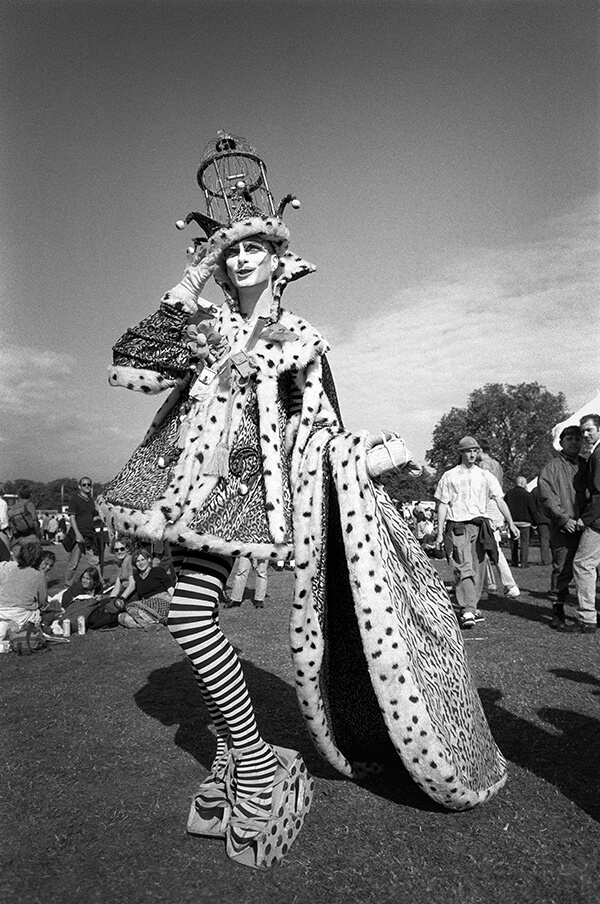

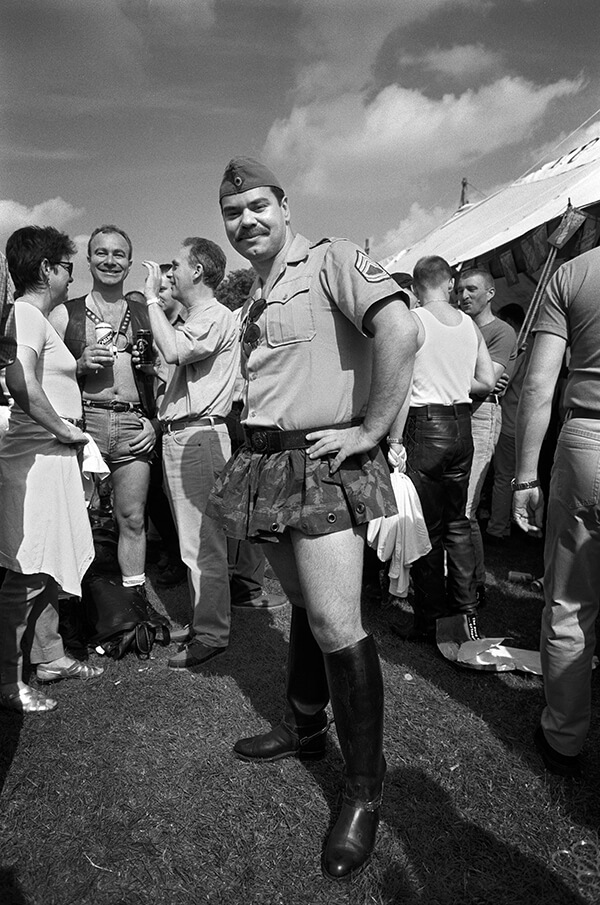

I get this question a lot. Sometimes the question comes from people outside our communities, but more often, it’s from folks who are themselves lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. Occasionally it’s even aggressive, betraying that the speaker believes the speedos and leather and drag dotting the crowds somehow constitute participation in our own oppression. What’s clear to me in these cases is that the person is asking from a place of shame. And it’s tough to know how to respond because that shame is the exact thing we’re marching against.

Most of us don’t grow up with parents who share our sexual orientation or gender identity. For many, we may not have had any visible role models at all. We don’t come up learning that the ways we love and fuck and form families are contemporary manifestations of histories and cultures that are themselves as old as humanity. And, as a result, too many of us never learn that we, as LGBTQ people, are just as worthy of love and belonging as everyone else.

For me, what makes shame easiest to understand is placing it next to another feeling—not pride in this case, but guilt. Guilt is what we feel when we’ve done something wrong and we assign that error to our actions. Shame, by contrast, is when we turn against ourselves. In that case, we say—and, on some level, believe—that not only were our actions wrong, but we are inherently wrong because of them.

The stakes here are shockingly high. Consider the work of Brené Brown, our country’s leading researcher on the subject. Brené has documented how high levels of shame are correlated with many of the things that destroy our lives, from addiction, to depression, eating disorders, self-harm, and aggression.

What makes this even more difficult is that we don’t just experience these feelings on an individual level. When we haven’t learned to love ourselves—and often even when we have spent years working towards that—we may be prone to feeling shame at the community level. The actions of others who share our sexuality, nationality, hometown, or last name may leave us feeling humiliated and self-hating. So seeing a drag queen or a motorcycle dyke out on the street during Pride Month reminds many of us that we’re not so sure we like being queer and that, deep inside, we’re not so sure we like ourselves at all.

My intention in writing this is not to shame those who are uncomfortable with pride. The truth is that almost all of us have felt something like that at some point in our lives and it isn’t an indication that we’re defective. My recommendation to everyone looking at these photos from the long history of our marches is actually to get more deeply in touch with the memories of that discomfort, whether we had it at a march or in a gay bar or any other LGBTQ space. Sitting with that feeling can be instructive and ultimately transform ourselves into our own best teachers.

When I feel shame, my heart beats faster and my brain starts buzzing. I start over-performing and seeking the praise of others to give me some sense of relief. But the bodily experience of shame is different for each of us and learning our unique manifestations is the first key step in building our ability to cope.

Brené Brown says one of her greatest goals is to start a national conversation about shame. For our part, many LGBTQ communities around the world have been having that conversation, marching in these parades for all these years. The pride we cultivate in these spaces may never fully take the place of our shame, but the more time we spend with the feeling, the dimmer it becomes.

Jack Harrison-Quintana is Director of Grindr For Equality for Grindr and was recently named one of Fast Company’s Most Creative People in Business.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox