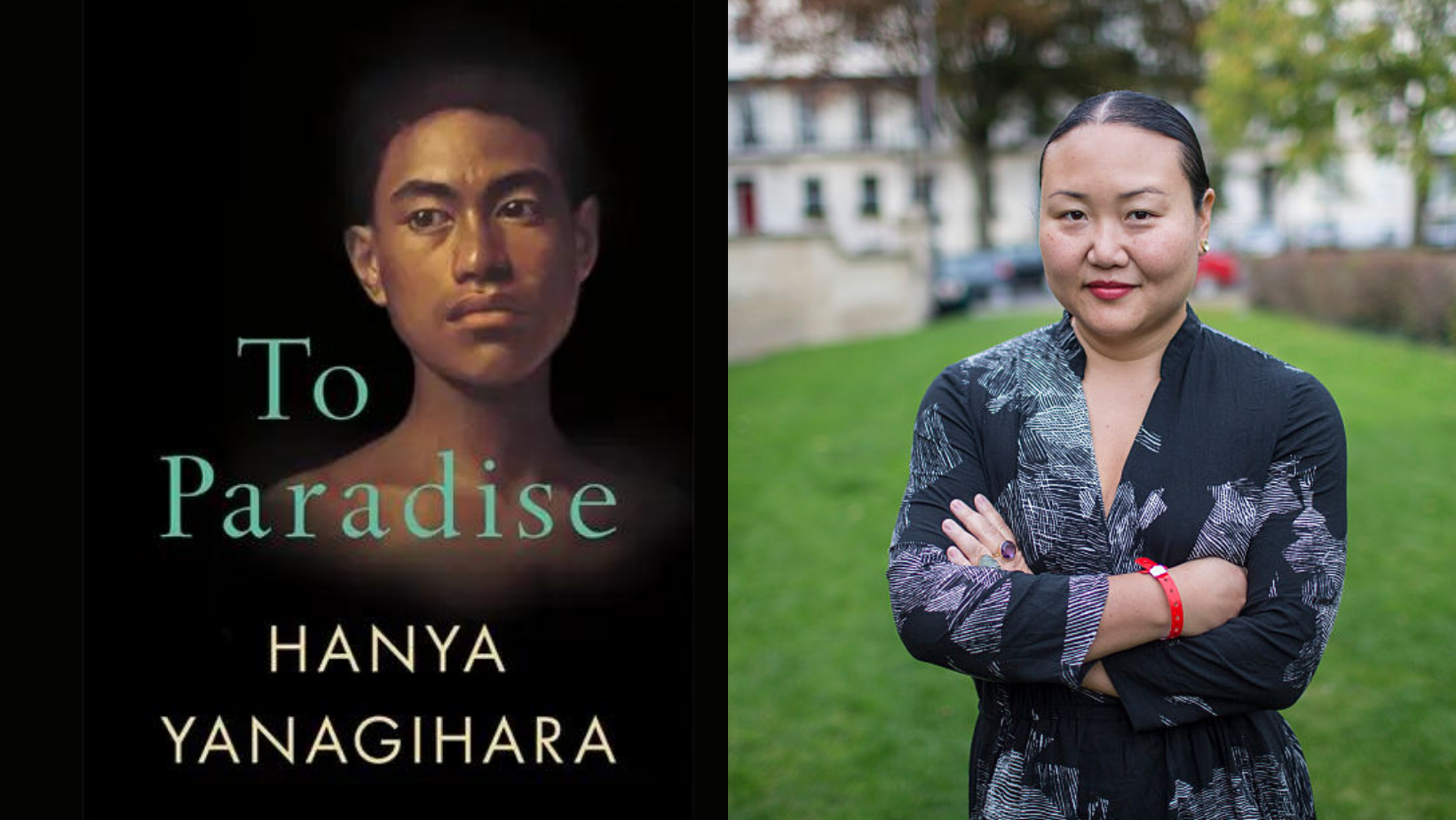

When I saw snippets of the early reviews of Hanya Yanagihara’s third novel To Paradise, laden as they were with resentments of the success of her blockbuster second novel A Little Life, I was both annoyed and bored. Of course To Paradise was edited. Was it edited to contemporary fiction’s standards of sentence-level utilitarianism? Nope! Her syrupy, complex sentences are mouthfuls in Book I especially, and sure, it’s too long. But is there style, a rhythm of some shape? Yes. She fetishizes people fetishizing their own wealth and class positions, and of course that means she’s usually fetishizing whiteness, even when her characters aren’t white. Of course, Hanya (we don’t know each other, but allow me to presume familiarity, as a bit) is the omnipotent overlord of her books’ characters. All authors are. And no, her work is not interesting because it provokes empathy, nor is its central pathology its fixation with trauma, as many have said about A Little Life. Allow me to attempt a more interesting critique for this latest edition of #bennyboosbookclub.

Across two novellas and one novel, To Paradise builds new worlds and timelines to interrogate the dream of escaping one’s family to enter a new family that, shockingly, contains many of the same pathologies as the original. “When you have been rejected by parents, you will never stop trying to please the parental figure,” Hanya proclaimed in a recent New Yorker profile. Isn’t it funny how in other books, criticism calls this Freudian core wound a protagonist’s “motivation?” When most literary fiction disguises their inevitable failure to satisfy that desire (or heal that wound) with clever but fluffy plotting, it’s lauded instead as an example of that trusty literary archetype, the flat character.

So if all protagonists are meant to have goals and motivations, don’t all works of literary fiction have a trauma plot? Hanya is just upfront about where her characters’ traumas come from. I do not read her books—or read in general—to empathize. That’s so boring. I read to ~dissociate~, as the kids say so casually. I like that the two Hanya novels I’ve read are quite unrelatable to me. They allow me to feel feelings and ask questions indirectly and arrive at sensations I wouldn’t have arrived at if I were reading a book that was trying to make me feel “represented.” Enough!

Maybe it’s the Pisces in me that’s drawn to Hanya’s absurd fantasies, taken to even greater heights in To Paradise. Hanya’s sentimentality—the grand intensity of emotion and yearning for seemingly unattainable love—sings because it attends to the aching hearts of her always coming-of-age characters. Wealth and domestic comfort are but topical analgesics and torn bandages. Are the morbidly gruesome depictions of all the violence Jude experienced as child in A Little Life essential to the novel? Perhaps not. But as measured recollections in a deliberately over-long book that culminates in his tragic demise, they don’t feel voyeuristic. Taken in sum, that book suggests how trauma disables Jude over the course of his life, slowly but steadily even as so much else in his material life sparkles. The materiality of his psyche lashes out on his body. Past what point is healing insurmountable? Of course it’s a melodramatic question, and the book’s breadth asks it heavy-handedly.

I do not read her books—or read in general—to empathize. That’s so boring. I read to ~dissociate~, as the kids say so casually.

But if, dear reader, you’ve ever dated someone who’s told you earnestly, “It’s not you, it’s me,” did you not wonder a version of this question about them? The pandemic’s upending of so many relationship priorities has made painfully clear how people are dealing with traumas of trust, abandonment, and safety through embarrassingly childish behaviors. If you haven’t had to deal with this, then bless you. Though avoidance, too, is a trauma response.

Book I—titled “Washington Square” and set in 1893—is loosely inspired by the Henry James novel of the same name. The opening of Hanya’s version reads like a 19th-century Succession, except there’s no fight among the heirs, only vague sibling resentment as the homosexual patriarch announces that the protagonist—the first David we meet in To Paradise—will inherit the family’s primary home. White intergenerational wealth, but make it gay. They’re as old money as old money gets in this alternate America, where the Northeast has formed the Free States in defiance of the abhorrent homophobia of the South and West. Not America, but exceptional. Of course, this worldbuilding twist is narrow: Black people are still enslaved elsewhere and resented in the Free States. Indigenous societies are being genocided away. At the other end, the conceits she explores in Book III spiral beyond her grasp.

Like many of my favorite artists, once Hanya decides on a bit, she commits to the bit.

As in A Little Life, “Washington Square” finds intimacy and spectacle in the mundane revelations of being with other people and being near their bodies. David’s discovery of tender physical affection and words of affirmation from a lover is made all the more saccharine by allusions to his unspecified chronic illness that sequesters him in stuporific episodes. By the time the narrative scoops back to reveal some of the illness’s origins, I’m inclined to just call it heartbreak. Perhaps David’s heart is more delicate than most, but everybody grieves.

Like A Little Life’s Jude, “Washington Square”’s David enjoys going on walks throughout New York City. Same, bestie, same! Jude and Book I’s David want to enjoy such simple pleasures, they want to communicate sincerely but are afraid of disappointing their interlocutors. David wants to tell potential future husband and Daddy-figure Charles he doesn’t love him because he loves Edward, a generically attractive but impoverished man, an Austenian Mr. Wickham. Does “Love conquer all,” even wealth?

Hanya’s sentimentality—the grand intensity of emotion and yearning for seemingly unattainable love—sings because it attends to the aching hearts of her always coming-of-age characters.

To Paradise’s protagonists don’t speak up for themselves because they’re for some strange reason distracted by the aftereffects of their traumas. Duh! Their disabilities are both constant and unpredictable impairments to daily life. It’s almost as if Hanya has a point to clarify that’s both more pointed and more subtle than the central argument critics extracted from A Little Life to patly dismiss it. What if her attention to the afterlives of pain wasn’t about extreme excess (as she herself has said) or torture porn (as critics called it?) What if she’s spending more page time to interrogate those insufficient bandages people put on their hurt?

Over the three books that make up To Paradise, the narrative structure fractures more than exponentially, like a virus mutating or trauma seeping over time, across generations. Hanya’s characters’ bodies definitely keep the score, even in the narrower splinters of the story. They also become more remote. Reader, if you’re looking for an A Little Life remix, I suggest you stop after the first half of Book II, which only becomes, not trauma porn, but relentlessly bleak and almost impersonal.

In the first half of “Book II: Lipo-wao-nahele” (taking place in 1993), David is not only young but healthy. He’s escaped a neglectful father and expectant grandmother in Hawaii to make it in… New York. There, he chooses reliable and affluent daddy Charles as his partner with equal parts relief and resignation. From decades in the future, David recounts the last dinner party before one of Charles’ friends leaves the U.S. to die of AIDS in Europe. David considers the mortality of his daddy-boyfriend’s generation and how precipitously he escaped into his own future of health, ease, and a new boyfriend. Near the end of Book II, Part 1, the reader receives an explicit hint. Was David’s search for such security a trauma response? Not my life, but I know what he means!

Book II’s first David’s father is also named David, and in the flashbacking second half, he chooses the manipulative romantic Edward. As young adults, Edward seduces older David not with love, but another illusory paradise: repatriation. Unlike in part 1, his method is not sex and flattery, but steady attention. He brings David to a bar where a Black man named Bethesda gives a rousing, five-page monologue on how the settler-colonial state U.S.A has taken Hawai‘i from them. That those five pages are the extent of the political education David receives foreshadows his demise under the influence of newly radicalized Edward.

It’s a fantasy that some man—much older or not, husband or grandfather, Charles or Edward—will Daddy-ishly save our dear protagonist, nevermind the faceless peasantry

The critiques of the United States in this novella unravel with more deliberation, as do their afterlives in the trauma plots of both Davids. Hawaii’s annexation into the U.S. unsettles both David and Edward, but it’s Edward who lacks the safety net. His single mother is working two jobs but, of course, fulfills her stock character role in this fable as the poor woman with an unwavering generosity (see jars of mango jam) and infinite zest for life. So of course, when Edward is orphaned and doesn’t deal with his grief, it festers and undoes both him and David.

The bifurcated chronology of Book II has a lot to suggest about the nature of intergenerational trauma. When David the father bumps his head and can no longer walk, the blunt-force trauma is quite literal, but cannot be separated from the repetitive strain that he’s faced and subjected his son to under Edward’s control. These forces are inseparable and cumulative, such that even trauma feels too reductive, too easy a term to encapsulate either David’s woes and wishes.

Book III, titled “Zone Eight,” Hanya’s pre-Covid pandemic novel, also follows a past and present timeline colliding. Who our David, Edward, and Charles are as people is obscured. Our nameless 2093 protagonist refers to the man who shares a room but not a bed as “my husband” until nearly the end. Our epistolary 2040s-to-present narrator signs his letters as “C.” and calls his son “the baby.” To Paradise’s three timelines don’t seem to exist in the same universe, but these echoing characters could seem to wonder if the conventional ménage à trois will play out differently in a different time. Over the course of the three books, romantic coupledom housed in easy domesticity becomes an increasingly depressive organizing principle.

Hanya’s worldbuilding in Books I and III—the ones most removed from present-day—is often clunky. C.’s epistolary exposition (“There had been, as you recall, a good deal of debate about […]”) in Book III can feel especially labored. But as his letters reach further into the authoritarian future, their endings become more speculative, their romance both more hopeful and darker for how out of touch with his reality they seem. The archly philosophical musings (“We are the lizard, but we are also the moon”) drip with more irony than profundity. Is it annoying? Of course. I am reading a letter written by an agent of the state wringing his guilty hands over having constructed fascist, genocidal solutions to deal with a century of pandemics.

The racial groups of this dystopia are Black, white, and “the rest of us.” Like the epithetical characters’ real names, the characters’ skin tones and relative darkness and brownness become oddly oversignified late-stage revelations. Why? In describing a homosexual-led rebellion in 2067, the 2093-protagonist’s mention of “racial minority groups”’ participation reads like an afterthought. In 2045, C. meets Aubrey and Norris, this book’s initial owners of the recurring Washington Square home. That Aubrey is Black and Norris is Asian comes as both surprise and offense to C., for the old queens display artifacts of his (but not their) native Hawai’i so proudly in their home. While not as long as Book II’s 70-page party scene, more than enough pages are given to this dinner party of the ruling class. But why surface still complex racial dynamics with such reductiveness? (C. initially perceives Norris as Hawaiian, etc.) Ultimately, as protected as they are from the illnesses ravaging the indiscriminate masses out there, these Rankine-esque dinner party conversations cease to matter. This society’s queer, multi-racial elite are still human, still susceptible to illness, and their wealth—even before it’s seized by the state—cannot save them.

Is it annoying? Of course. I am reading a letter written by an agent of the state wringing his guilty hands over having constructed fascist, genocidal solutions to deal with a century of pandemics.

In this apocalyptic iteration of the trauma cycle, C.’s granddaughter becomes afflicted with one of the pandemic illnesses. and treatment for it permanently disables her. Hanya does not refer to her affliction explicitly as autism but it sounds quite like it’s on the spectrum. This causation is just one appalling myth of contemporary society that she reproduces in To Paradise. But does she fully explore its implications?

Despite employing a full staff and suite of video monitors, C. fails to safeguard his disabled granddaughter’s childhood explorations of Washington Square Park. Pages and decades later, the adult granddaughter navigates a public arena where the surveillance state uses devices called “Flies” to track any excessive displays of emotion. In his trepidation that a new drug might “further deaden” his granddaughter, Grand-Daddy C. reconfigures an ecofascist logic he employs to excuse state-run death camps to express care for his family. He muses that her neurodivergence makes living under a repressive regime easier, as if the infantilization of disabled people by Daddy somehow justifies a government’s disempowerment of all people, or vice versa.

Do I enjoy reading Hanya’s 700-page, intricately constructed work, an artwork ornamented with the kind of splendor her oft object-fixated characters covet? Overall, still yes.

This perhaps is the heartstrings-tugging emotional center of all of To Paradise’s sections and its shuffling David-Charles-Edward threesomes. It’s a fantasy that some man—much older or not, husband or grandfather, Charles or Edward—will Daddy-ishly save our dear protagonist, never mind the faceless peasantry. In Books I and III, that delusional escape route is coupled with a homonationalist fantasy that a nation-state permissive of gay existence will save a society, never mind the racial and class stratification or the imperialism undergirding it all. Yawns. Jasbir K. Puar taught me better.

But this is speculative fiction. Hanya does not necessarily approve of the regressive thinking of her characters or their worlds, but it feels like a fraught choice to tell stories from their point of view. Does following To Paradise’s mostly unsympathetic, wealthy, and often self-pitying characters offer revealing interrogation into totalitarianism’s looming inevitability? Perhaps. At this stage of my personal political education? Perhaps not.

What if I didn’t task Hanya with teaching me about totalitarianism, ableism, or legalized homosexuality? (Trans people receive, perhaps, two mentions. So what?) It’s just a book, flawed like any other. Do I enjoy reading Hanya’s 700-page, intricately constructed work, an artwork ornamented with the kind of splendor her oft object-fixated characters covet? Overall, still yes. Despite C.’s fears, his adult granddaughter develops a complex emotional life and her earnest contemplation of it all, in spite of the regime’s tightening restrictions, is movingly alive. Taken with A Little Life, To Paradise shows just how much Hanya relishes the living of a life—queer and disabled even if she avoids those words—and its small pleasures even as it’s riddled with trauma, unrealized dreams, and death.

But what does this matter anyway? Hanya is too successful to bother with all of our little reviews. I read my free copy of her latest book. I am getting paid to say that the people who hate-read Hanya for sport—those who zealously project onto her these insufferably neat theses about how she only romanticizes the tragedy of queer and disabled people—are telling on themselves. For, who among us hasn’t romanticized their own trauma narrative?♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox