Jordan’s first and only LGBTQ magazine has been shut down by the country’s government, but the publication continues to thrive in the face of persecution.

My.Kali, an online magazine based out of Amman, was censored by Jordanian officials in July 2016 after launching an Arabic version of their websitewhich, prior to that time, was available exclusively in English. Khalid Abdel-Hadi, the publication’s founder, tells INTO that the Arabic edition triggered a “backlash” within the nation’s “sensationalist media.” Local news, he says, demanded to know why a “deviant, perverted magazine” was allowed to exist in the conservative Muslim nation.

Within a day of My.Kali becoming national news, he says it was “blocked.”

That controversy was reignited in July when Jordanian MP Dima Tahboub, who is also a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, led a crusade against the magazine. During an interview with the German publication Deutsche Welle, Tahboub claimed that “homosexuals” were “not welcome” in Jordan. She would add in a separate interview that queer people are mentally ill, as well as “alien to our religion… and the Jordanian people’s cultural norms.”

Following that interview, the minister filed a complaint with against My.Kali under Article 49 of the controversial Press and Publications Law. The 1998 legislation requires media outlets to obtain a license to operate. But there were two problems with her complaint. First, the regulation doesn’t apply to websites. On top of that, My.Kali hadn’t posted since 2016. Tahboub would nonetheless be credited for the publication’s demise in international media, viewed as a victory of right-wing Islamism over deviant forces.

Abdel-Hadi claims the backlash reignited extremist elements in Jordan that had come out against the magazine the year prior.

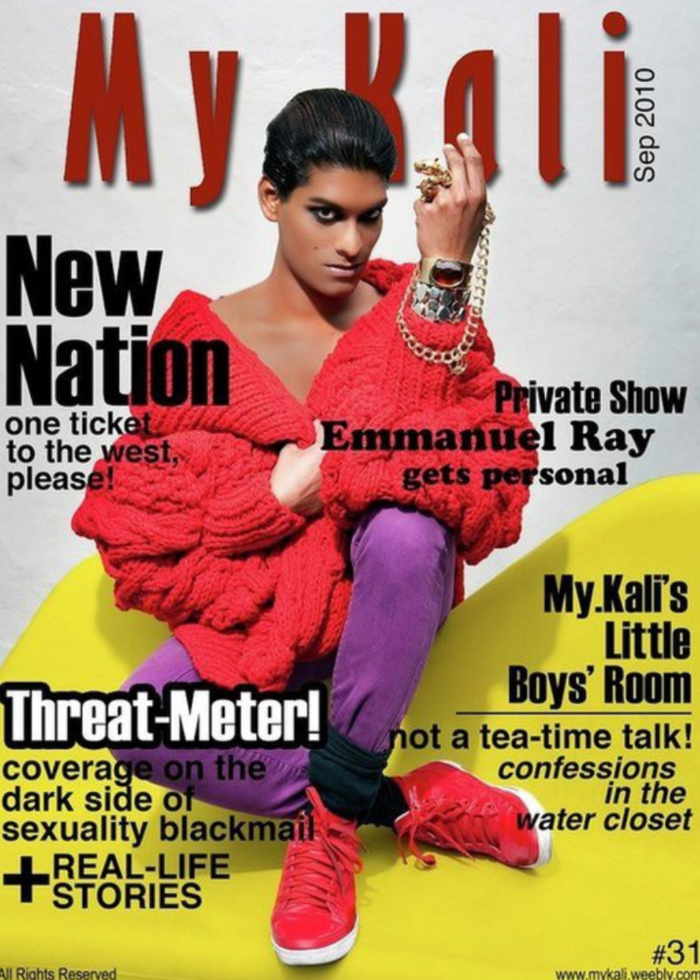

My.Kali, one of just a few of its kind in the Middle East and North Africa, has received numerous death threats over the past year. He says that Facebook commenters threatened to “crucify him” and “throw him from a building.” What makes these threats so chilling is that even though many LGBTQ people are forced to live in secrecy in the conservative region, Abdel-Hadi’s profile is very public. His face often graces the magazine’s cover.

But the 28-year-old says that My.Kali has faced opposition its entire existence.

Abdel-Hadi says he created My.Kali, which first began publishing in 2007, because he struggled to “find any resources that had to do with being LGBT and Arab at the same time.” As a gay high school student, the little media that was out there didn’t reflect his experience.

“I couldn’t identify with any of these characters or individuals,” Abdel-Hadi explains. “During that time, the only news we were hearing about LGBTQ people in the Middle East was about people in Saudi Arabia being hanged and imprisoned, people being arrested in Egypt and Syria, or people in Iraq were being killed by militia.”

The reason that My.Kali was online-only, Abdel-Hadi says, is because of privacy concerns. Even though Jordan is one of the only countries in the Middle East that doesn’t criminalize same-sex behavior, it can be extremely dangerous to be open about your sexuality. Three years ago police arrested 10 LGBTQ people for attending a party in Amman, even though the event was perfectly legal. Local authorities referred to it as a “disturbance of the peace.”

Abdel-Hadi compares My.Kali to reading Playboy, the men’s magazine long-known for balancing award-caliber journalism with more risqué material. The difference, though, is that people don’t usually kill Playboy readers for sneaking a peek at T

“Once you hold a Playboy and walk in the street, people will judge you based on what you’re holding,” Abdel-Hadi says. “My.Kali is very controversial in the Middle East and North Africa simply for being an LGBTQ magazine. We don’t want to jeopardize the lives of people who love our work. They shouldn’t have to hide it under their bed.”

But Abdel-Hadi learned first-hand just how vulnerable that privacy can be.

When he was just 18, Abdel-Hadi was exposed and outed as the creator of My.Kali, which at the time was modeled after American publications like Seventeen magazine and Teen Vogue. All he wanted, he says, was to create a space where young people like him could express themselves openly. Abdel-Hadi worried, though, that the sudden press coverage meant that he would be “arrested or killed.” Nothing happened.

In spite of its vocal critics, My.Kali has continued to grow over the past decade. Abdel-Hadi says that the magazine developed into a “hub” for LGBTQ people in the region. About 40 people contribute to the publication on a regular basis, many of whom live outside of Jordan. Writers live in countries like Morocco, Palestine, and Syriaamong many others.

A.W. Rahman, the pen name of a contributor who asked to remain anonymous for this article, heard about My.Kali when she was attending college in 2009. At school, she only had a couple friends who were LGBTQ. The magazine made her feel like they weren’t alone.

“It felt like we were more than two or three people in the middle of nowhere,” says Rahman. “There are people who live lives similar to ours.”

What made the magazine so impactful is that she didn’t have the family support that others might take for granted. Rahman claims that it can be difficult for friends who live in Western countries to understand why she hasn’t told her parents that she’s a lesbian. But Rahman explains that it can be next to impossible to be openly LGBTQ in a society that’s “community-based,” instead of rooted in values of individualism. There’s “no place for being different,” she says.

“I had this discussion recently with someone who said, ‘If your family loves you, they would accept you,’” Rahman recalls. “Here it works the other way around: If you love your family, you wouldn’t want to disappoint them.”

Saja, who also asked to use a pseudonym for this piece, claims that the problem is that there’s very little knowledge about LGBTQ identities in Jordaneven among those who are queer or transgender. Growing up in Amman, Saja knew that she was different from her peers, but didn’t have a word to describe what she was feeling inside. She didn’t know transgender people even existed until she was a teenager.

Now 23, Saja claims that her parents were “open-minded,” but living as a trans woman in Jordan was never a real possibility. Saja says that she had to “flee” to Germanywhere she is currently enrolled as a university studentto able to be herself. Walking home late at night in her hometown, Saja would fear what would happen if men on the street “clocked” her for being transgender. Because Jordanian communities are often small, everyone knows each other. That makes anyone even suspected to be LGBTQ a potential target.

“It’s like a prison if you have to stay,” she says. “It’s torturous.”

Abdel-Hadi doesn’t deny that living in Jordan can be a struggle for LGBTQ people, but he hopes that My.Kali can show its readers that the country is “evolving,” in ways that are both good and bad. He believes that his magazine is proof of that. Although it’s known as an LGBTQ publication, Abdel-Hadi claims that My.Kali has a wide following across the Middle East and North Africa, even among heterosexuals.

That’s because many of the magazine’s stories aren’t about queer themes at all, he asserts. It focuses on a wide variety of subjects, including art, entertainment, music, and culture.

The diversity of My.Kali’s content, Abdel-Hadi claims, serves a political purpose. His mission is to show the average Arab citizen that his LGBTQ neighbors are a part of everyday life: They go to concerts and films, and they’re praying at the local mosque. Abdel-Hadi explains that he doesn’t want his magazine to accidentally send the message that queer and trans people are “isolated” from any other community.

“We don’t want to put up any partition between LGBTQ people and non-LGBTQ people,” he says. “We want to open it.”

Despite being blocked by Jordanian authorities, My.Kali will continue to tear down those barriers. The website, which was originally housed on a Weebly blog, moved to Medium after it was shut down by state officials. The old site now redirects to its new publishing platform. Because ministers have no authority over what’s posted on Medium, officials cannot challenge what My.Kali decides to print there.

The publication has yet to run its first issue at its current home. But in the meantime, loyal readers can access old cover photos and browse through a modest selection of its archives.

My.Kali’s creative team agrees that ensuring the publication has a long, prosperous future is critical for the LGBTQ community in the Middle East and North Africa. Saja says losing My.Kali would be like being trapped in a “huge, dark cave that has a little candle and then that candle dies off.” Rahman adds that keeping that flame alight has the power to inspire the hope that queer and trans Jordanians so desperately need.

“Every small change might lead up to a big one 20 or 30 years from now,” Rahman says.“Most people find it hopeless [to be LGBTQ in Jordan], but I’d rather try and fail than not try at all.”

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox