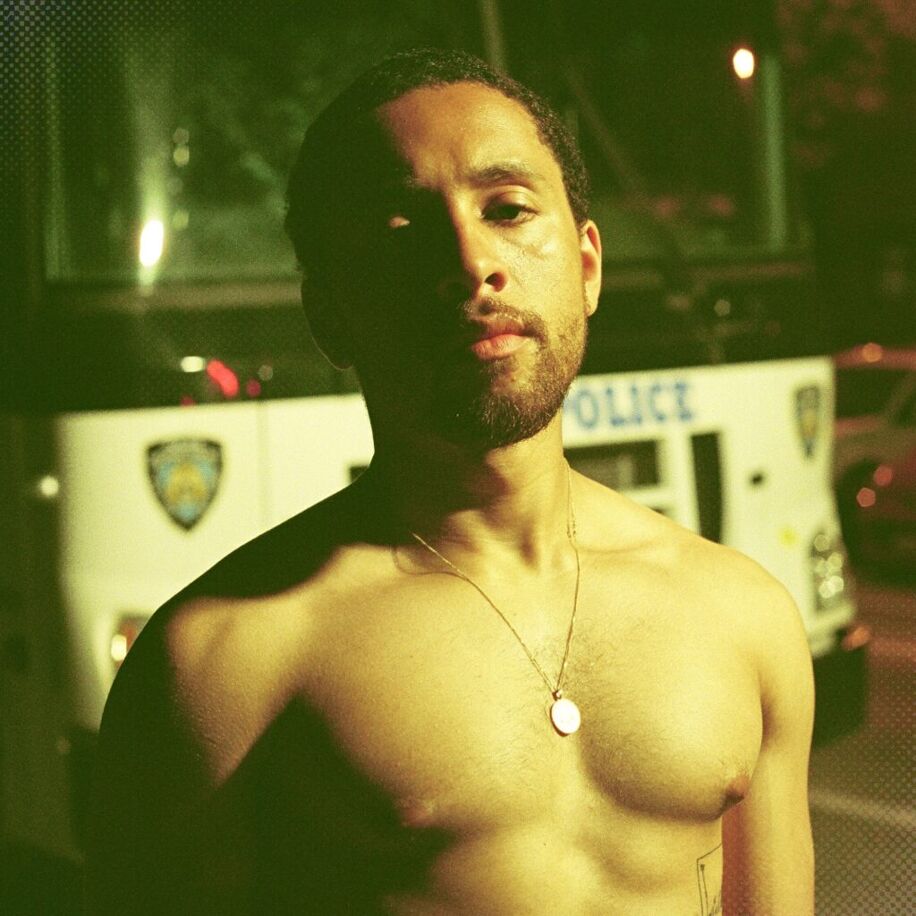

Over the course of the past decade, Jaboukie Young-White has become America’s sweetheart. Fans have gotten to know the comedian and writer through his performances on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, his writing and guest slots on shows like Big Mouth, Only Murders In The Building, and Rap Sh!t, and of course, his delightfully irreverent Twitter presence. But this week, Jaboukie Young-White—better known mononymously as Jaboukie—has shared his debut album, All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel, on which, he takes inspiration from his Jamaican upbringing, and shares poignant stories about moving from home-to-home as a child, coming to terms with his sexuality, and embracing every dimension of himself.

At the time of our interview, Jaboukie has plans to finish off the year in a promising manner. We catch up with him weeks before the release of All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel, where he Zooms with us from his lush backyard at his Bushwick home.

“I really lucked out,” Jaboukie says.

Jaboukie was born to Jamaican immigrants and raised in a musical family. His father was a DJ in various Chicago venues, where he spun dancehall, reggae, and hip-hop music. He recalls hearing his father perfect his mixes in the home basement, and says the music would “rattle the house’s foundation.” As a result, Jaboukie’s music is very much bass-heavy and drum-driven. His brothers, Javaughn and Javeigh are also instrumentalists in their own right.

All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel marks the first time all three of them have collaborated together musically, but Jaboukie says the process felt very familial.

“In the same way that with your siblings, it’s like, all three of you have different takes on the same event,” says Jaboukie. “It’s like when you bring up a memory, and because you’re all experiencing it from different mindsets and different points of development, my brothers remember it a certain way. I’m like, ‘Yeah, but you were eight and I was like, 11 or 12, so I was seeing it in a different way.’ I think that translated a lot to the way that we make music in the same way that we all kind of have like different takes on the same event. We’re all pulling from the same musical influences, but taking something different from it.”

Related:

New Brandi Carlile, Tayla Parx, and More on This Week’s Queer Music Mixtape

This week’s mixtape is full of hot new collaborations, colorful pop moments to get you dancing, and all the queer romance one could possibly want.

In his adulthood, Jaboukie has explored many avenues–standup, screenwriting, acting, and now, music. Perhaps this provides a parallel with his childhood, when he spent the tail end of his teenage years moving around after his family home burned down when he was 16. He and his family lived in a hotel while the “temporary insurance home,” as Jaboukie describes,” was being built. By the time his family had moved in, Jaboukie immediately decided that he wasn’t going to get too attached to the house, as he was a senior in high school at the time, and would be going to college the following year.

“I go to college, and I’m in a place for a year, and a place for another year, and a place for another, and then I dropped out,” says Jaboukie. “And then I’m broke, and I’m like, here for a few months, then here for a few months, then here for a few months. I was living this like really nomadic lifestyle to the point that I turned 26, and was renewing my lease on my apartment. And I was like, ‘This is the first time I have been in a place for more than a year since I was 16.’”

This transient point of his life inspired a song from All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel called “Cranberry Sauce,” who which he explores the things that make a house–and certain people in his life–feel like home. Jaboukie has come to understand that his coping mechanism of not getting attached to places for too long has made itself present in his relationships with people.

On a verse of the song, Jaboukie sings, “Tried building with someone new / Then the flood came through / And the generator blew / And the walls caved too / Some repairs been overdue.”

“It can be difficult to see what role you played in bringing that on yourself,” says Jaboukie.”It’s hard to digest the loss and also the culpability and potentially the guilt at the same time.”

According to Jaboukie, the album’s title refers to the “low end of the bass,” which he utilized on most of the album’s songs. It also alludes to a Jamaican proverb, describing the idea that one will eventually face the repercussions of their actions.

“‘All who can’t hear must feel’ is an adage that, at its core, is saying, if you can heed the warning, you’re going to feel the consequences,” says Jaboukie, “But in practice, it is mostly just used before kids get a spanking. That is usually the last, or the second to last warning that they get before the spanking.”

Jaboukie, himself, hadn’t been to Jamaica since he was five years old–that is, until, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, around the time he was 26. When he came back to the States, the country was in the midst of the pandemic, as well as nationwide protests against police brutality.

As a Black and queer person in America living through it, Jaboukie contemplated what life would be like if he lived elsewhere. He considered how his parents immigrated to America, and realized he didn’t have to stay where he was. He admits he has gone no contact with his father–leaving Chicago out of the question. He’s thought about living in Jamaica, however, the country’s treatment of LGBTQ+ people has driven Jaboukie away from the idea.

“When I go to the area of Jamaica that I’m from, it’s very small town,” says Jaboukie. “Everybody knows each other. I’m there with my grandma, and I feel I have amnesty in a way. Even though a lot of that is just driven by the fact that when I go back, I offer help to people and stuff like that, so I understand that’s motivating it. But then, thinking about that, I’m like, ‘Yes, but all of those things are contingent on the fact that I’m not expressing sexuality, and that I am straight-passing in those spaces.’”

Related:

Selena Gomez & Miley Cyrus Are Dropping Bops on the Same Day

Our favorite Disney teen queens of the 2010s, are gearing up to release new music on the same day.

This painful self-awareness inspired the song “Incel” from All Who Can’t Hear Must Feel. Though the word “incel,” which is a portmanteau of “involuntary celibate,” often refers to a straight man, whose misogyny often pushes women away from him, Jaboukie put a spin on the word, as he knew he would have to repress his sexuality if he were to live in Jamaica long-term.

“Tired of existing / But fighting to exist still / Launch a lazy punch and kick at the nothingness,” Jabouke sings on the song’s chorus, over a drum-and-guitar driven instrumental.

But throughout most of the EP, Jaboukie is unapologetic about his sexuality and feverous in his displays of queerness. On another one of the album’s songs, “BBC,” Jaboukie reclaims a term rooted in the fetishization of Black men, and boasts about having “bad bitch coochie,”–which more so refers to a magical energy Jaboukie posseses, and not necessarily to body parts.

Equally as captivating is “Not_Me_Tho,” on which Jaboukie celebrates being a “free ho.” In the accompanying music video, Jaboukie is seen walking around a metropolis wearing lipstick, heels, white leggings, and a green dress.

No matter what medium Jaboukie uses to express himself, there is always an element of queerness and camp in his art. He can’t talk about his upcoming film and TV projects, given the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike, but he is grateful to have these platforms to express himself.

But despite how far we’ve come, in terms of intersectional diversity onscreen, Jaboukie feels that representation on its own is barely scratching the surface of equality and safety for LGBTQ+ people.

“I find that the more visibility that we get without having the infrastructure and the institutional protection, it’s actually dangerous,” says Jaboukie. “And I’m not saying it needs to stop by any means. We deserve to be seen, and we deserve to be valued, but we also deserve to be safe. I don’t want to have to be considered ‘brave.’ When I came out, people were like, ‘Wow, you’re so brave,’ and I was like, ‘What do you mean by that?’ When they say it like that, it sounds like a threat, like, ‘What are you saying I have coming my way?’ What if we flipped it? And it was like, ‘What are you doing to protect people?’ I think that there’s a lot more work to be done.”♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox