Every morning I steel myself before firing up my computer for the day. Writing for a living means I always have to take a look at the news cycle as early as possible, which usually means I grab my MacBook before I grab my toothbrush. Ever since the sexual misconduct of Kevin Spacey, Jeremy Piven, and Louis C.K.; the showrunners of The Flash, Mad Men, and The Loud House; and most recently, Charlie Rose has dominated the headlines, I’m forced to remember my own sexual assault before I even put on pants.

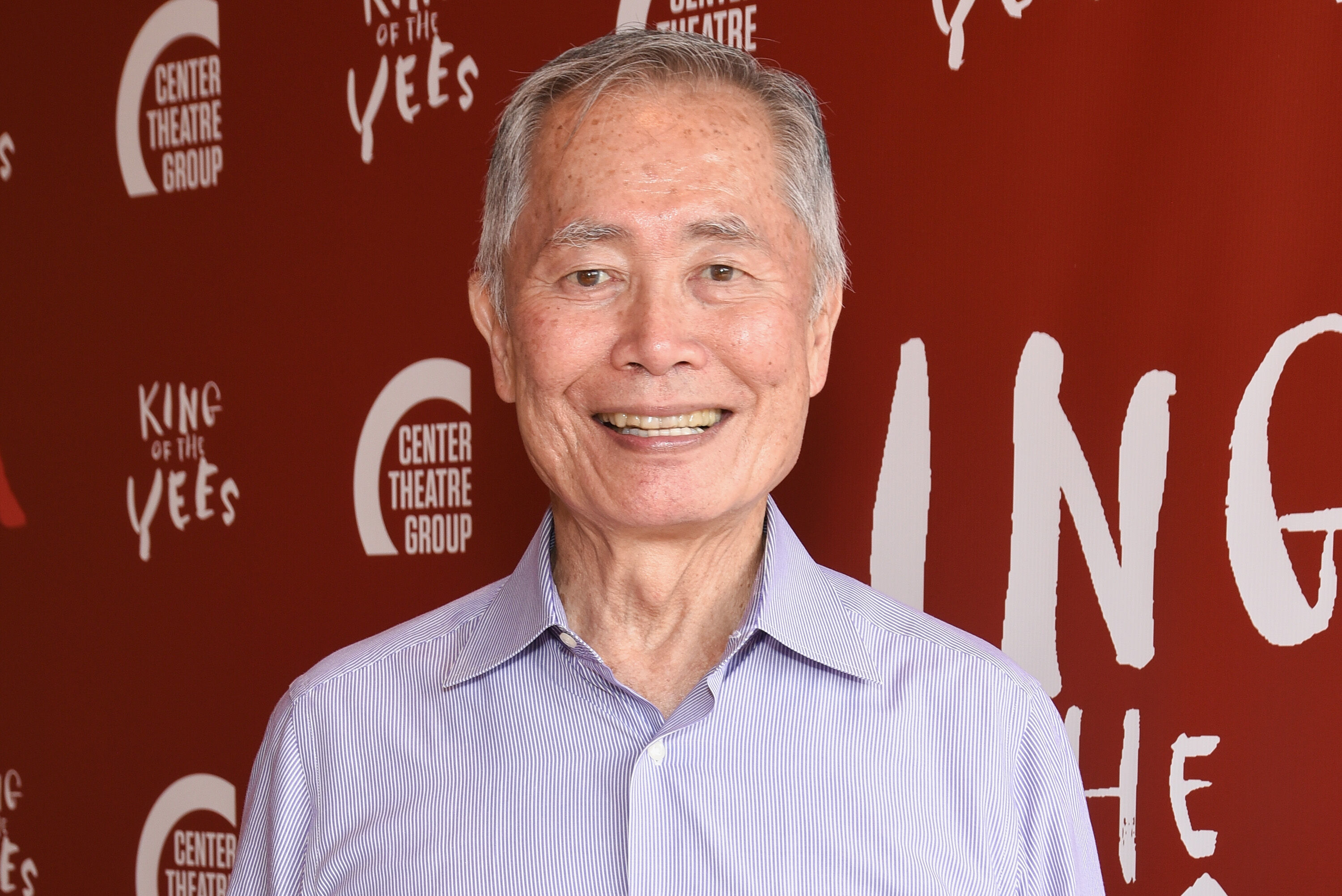

Seeing men held accountable for decades of toxic (and often explicitly illegal) behavior is fantastic, even though it seems like the news will permanently carry a trigger warning. But when I read that America’s gay uncle, George Takei, may not be so squeaky clean, I felt the desire to defend his honor. This desire completely conflicts with who I am; not a single one of the other men accused of sexual assault or harassment elicited that kind of response from me.

But unlike another straight white male actor being forced off of his show, losing Takei as a role model is actually damaging a lot more than just his own reputation. For a survivor of assault, the news stung for every possible reason.

On November 10th, former model and commercial actor Scott R. Bruntonalleged that the openly gay Star Trek actor sexually assaulted him when Brunton was then a 23-year-old living in Los Angeles in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. After being invited into Takei’s home, he claims that he was drugged and passed out. While unconscious, Takei attempted to take the young man’s clothes off without his consent. When Brinton awoke in horror, the 80-year-old allegedly told him, “I am just trying to make you comfortable.”

Brunton said he came forward specifically because Takei spoke out against the numerous sexual allegations against Spacey (15 at the time of writing) to the same media outlet a few days prior. “When power is used in a non-consensual situation, it is wrong,” he told THR in an Oct. 30 interview. Those remarks were covered nationwide, reprinted everywhere from People and Rolling Stone to Broadway World.

“It was the epitome of the pot calling the kettle black, what he was doing,” Brunton said. “And I had to call him out on it. And even though I’m gay and I understand he’s done a lot of good for the LGBTQ community, I just felt I had to say something.”

The next day Takeiresponded to the allegation on Twitter, and to me, it reads like an introductory course in how not to reply to sexual assault allegations. First, he dismissed Brunton completely, saying he was “shocked and bewildered” at Brunton’s claims. Then Takei denied even knowing Brunton: “I have wracked my brain to ask if I remember Mr. Brunton, and I cannot say I do.” Language like this implies that since Takei doesn’t recall the incident, nothing of the sort could have possibly happened. (Note to everyone: If you’re using the same reasoning as Roy Moore, you’re probably in the wrong.)

Adding insult to injury, Takei didn’t even bother to spell Brunton’s name correctly.

But despite the actor’s denials, he all but admitted to his misbehavior in an October interview with shock jock Howard Stern, which resurfaced after his allegations became national news. In the clip, Stern asks Takei if he’s tried to “grab anybody” against their will. Takei paused for a telling amount of time before saying that he’d previously tried to “persuade” men who were “skittish” or “afraid” by giving them “more than a gentle” squeeze. That description is nearly identical to what Brunton said Takei did to him.

Takei would apologize on Facebook, saying that he’s long “played the part of a naughty gay grandpa,” which lends itself to performative fiction. But his language is more than a poor choice of words or an impish public persona that got out of hand: It illustrates Takei’s complete ignorance of the gravity of sexual assault.

The Takei we’re all learning about this past week is “antithetical to his values and practices,” to quote his own response. When so many visible LGBTQ activists are white men, it’s been truly refreshing to see Takei consistently on the front lines, speaking truth to power. That’s why many folksespecially queer people of colorinitially hesitated to throw someone so often viewed as on the right side of the issues under a career-ending bus.

Ranier Maningding, who serves as an editor-at-large at the Asian-American website NextShark, claimed that he almost didn’t want to share the allegations when news of Takei’s misconduct initially broke. But he knew that doing so was the only option. “Part of me wants to wait, and another part is hating myself for even thinking about waiting,” Maningding wrote to his 225,000 fans on the Facebook page The Love Life of an Asian Guy. “Aren’t we supposed to automatically side with the victim?”

When more than 50 womencame forward to accuse Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault and harassment over a three-decade span, actresses like Gwyneth Paltrow, Rose McGowan, and Mira Sorvino were widely believed (which is all too rare in itself). Their bravery in coming forward in a series of interviews with The New Yorker and The New York Times triggered the #MeToo movement, in which social media users posted their own stories of harassment. But unlike the public reckoning against other famous men, the claims against Takei have been treated with a mixture of reticence and outright denial.

Karen Wehrstein, an activist and contributor to the liberal forum Daily Kos, decried the allegations as a “U.S. right-wing/Putin coordinated counter-op [sic]” in a piece that wasfeatured on the website’s front page over the weekend. Titled “Why the George Takei Allegation is a Weak Case, she questioned the timing and the facts of the allegation, as well as the fact that Brunton is Takei’s only alleged victim. Wehrstein claims that the THR report “[relies] on just one accuser plus four of his friends.”

That post amassed hundreds of comments and was shared on Facebook 3,800 times at the time of writing. Even though the article makes me cringe, it pains me to report that I relate to its thesis: It’s what I initially thought about Brunton’s story, too.

You can even feel the hesitation to malign Takei’s reputation in Brunton’s own allegations. Why else would someone who has experienced sexual assaulta fact that he has had to live with for more than 30 yearshave talked about “the good” his assailant has done for the LGBTQ community?

I have been in Brunton’s position before. Although my abuser wasn’t a beloved gay celebrity, a major reason I never reported my own assault was that I was positive no one would believe me. I wasn’t sober, so after I was assaulted, I felt much more embarrassed and ashamed that I had allowed myself to be vulnerable than anything else. Coupled with the feeling that I didn’t have “sufficient evidence,” that sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach kept me from reporting it. It’s also the same overwhelming burden of proof I held against Brunton, even against my better judgment.

Later, while in a much better place, I confided in a friend about my assault. It was the first time that I told anyone what had happened to me. Instead of support, however, my friend tried to debate me on whether or not I was raped in the first place. I didn’t tell the police because I thought they would react like my friend, and so I’ve never told anyone else until now.

I don’t hold that doubt against my friend, however. We all have biases, internal or external, that we have to work through to reach a conclusion we think is right. Unfortunate as it is, hesitation and doubt are normal responses to haveat least initially. After grappling with the internalized baggage that we all carry, a wave of common sense should wash over you, just as it did my friend. He would later apologize for doubting me. If his mea culpa were commonplace, we wouldn’t need to have the sexual assault revolution we’re having now.

It’s difficult to see Takei become yet another face of that movement because of everything he has meant to queer people of color for so long.

He has amassed a lifetime of history-making achievements throughout his five decades as one of the only gay Asian men in the public eye. When the actor starred as Hikaru Sulu in Star Trek, Takei entered America’s living rooms just over 20 years after Asian-Americans were placed in internment campsan oft-forgotten history he drew attention to in a celebrated 2016 Broadway musical. His very presence implicitly sent the message that men like Sulu deserve to be treated with the same dignity and respect as everyone else.

Since coming out in 2005, Takei has been one of the most politically outspoken gay celebrities. He has been a voice of reason and an advocate for equality, whether it’sdismantling the logic behind Donald Trump’s ban on open trans military service orprotesting Alabama’s attempt to block same-sex marriages in 2015. Until now, it always seemed like Takei got it.

But now the image of him as a predator and abuser will forever be printed as an asterisk under everything he’s done.

As of this writing, websites like Mic, Refinery29, Futurism, GOOD, and Upworthywhich leveraged Takei’s on-point perspective, as well as his 10 million Facebook fans haveended their partnerships with him.

If Takei’s finished as an idol and activist (and he should be), queer people of color don’t have that many figures of his stature left. Arguably the only household name who happens to be a gay man of color is RuPaul. I’m proud of out white gay men like Matt Bomer and Neil Patrick Harris for blazing trails of LGBTQ acceptance in Hollywood, but there’s almost no one at their level of achievement who looks like me. The only black gay man I could model myself after growing up was Arsenio Hall’s character in 1987’s Mannequin.

It’s something to scream into the void about (“Where are our possibility models?”) and to mourn when the few who do exist are proven not to be worthy of the throne.

The other reason so many double minorities cringed when Takei was implicatedpraying that this one wasn’t trueis that conservatives would likely point to both his sexuality and ethnic background as fueling his sexual deviance. In America, your race means everything unless you’re white. In 1870, the racist ideology of “Yellow Peril” depicted Asian men as violent rapistswhen in reality, the propaganda was a reactionary response to Chinese workers emigrating to countries with mostly Anglo populations.

If you’re a person of color in this country, you’re familiar with the concept of people putting you in a box labeled “scary” or “dangerous.” Now Takei has been permanently placed there. This is a major part of the reluctance to malign Takei. You may have dropped him as soon as you heard Brunton’s story, or like me, you may have needed time to process, even to grieve.

I was having a conversation the other day with the same friend that I confided so long ago about my sexual assault when the subject of Hollywood came up. I confided in him my long-held desire to be famous, which he dismissed as the aspirations of a wannabe starlet. But as I told him, I believe there are two kinds of fame: the kind that’s beneficial only for the individual and the kind that is beneficial for the world.

George Takei had the latter brand of celebrity: His was rarer, more beautiful, and much easier to lose.

Photography: Tara Ziemba/FilmMagic

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox