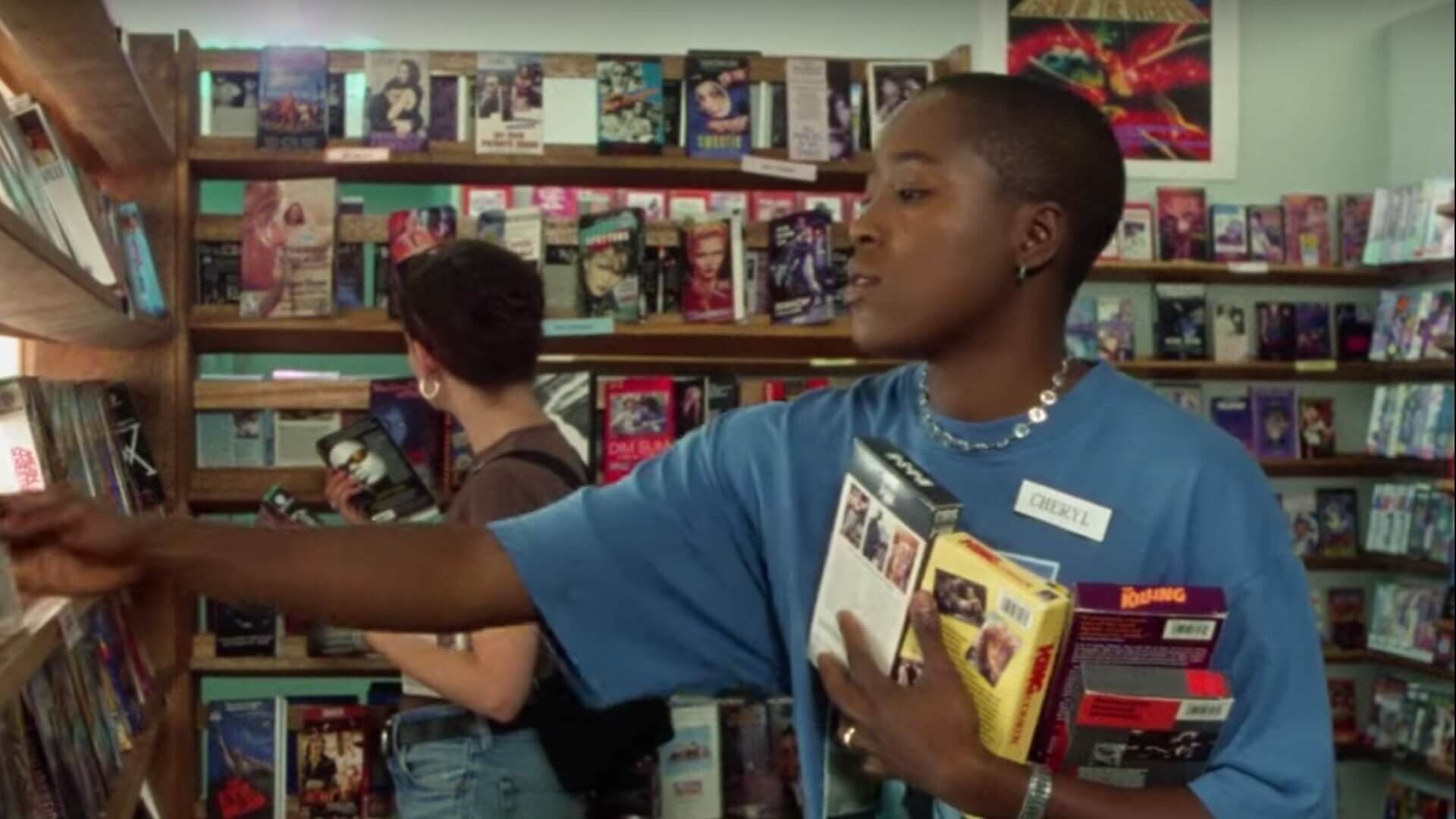

Time-stamped by 1996 with its movie rental stores and classic 90s fashion, Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman is far from a new tale; yet still, there are those who are just now hearing it for the very first time after the film entered the Criterion Collection last month. In the film, Dunye—who directed, wrote, and starred in the trailblazing feature—takes to the Philly streets on a mission of inquiry for black lesbians everywhere.

In the fictional docu-style film, the story of the “Watermelon Woman” unravels before the viewer just as it does for Cheryl (whose character bears Dunye’s same name) herself. One moment, an old film called Plantation Memories—directed by a white lesbian named Martha Page—is flickering on the TV. In the next, the intrepid filmmaker is launched into an all-consuming quest to find the identity of Fae Richards, the fictionalized film’s central Black star. In the mode of Black Hollywood actresses like Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen, Richards was restricted to the racist stereotype of the “Mammy” in her film roles. On top of that, she was deliberately left unaccredited, known only by the dehumanizing phrase: “The Watermelon Woman.”

Despite the many attempts of Plantation Memories to degrade Richards, Cheryl begins to envision the life of the person buried beneath Hollywood’s unrelenting prejudices and vows to unearth Richards’ true story. The instant that the protagonist picks up the camera and starts to film her own documentary, Dunye replaces Martha Page’s directorial eye with her own. Cheryl uses her own resources to create a legacy for Fae Richards both engaged with and guided by the experiences of Black lesbians.

Related:

Basketball, Theater, & Queerness Converge for Renita Lewis in Off-Broadway’s ‘Flex’

Actress Renita Lewis shares her experience working on the New York premiere of “Flex” by Candrice Jones at Lincoln Center Theater.

Zigzagging through the many grids of Philly’s Center City, Cheryl starts posing the film’s titular question to the casual passerby: “Do you know who The Watermelon Woman is?” Although none of the specific pedestrians can answer Cheryl’s question, the insight she seeks is waiting to be discovered within her own Black lesbian community.

Behind the scenes, Dunye’s film also drew from the richness of her community to create The Watermelon Woman‘s stunning meta-narrative. Whether it came down to gathering wardrobe for Cheryl’s iconic lesbian outfits or finding financial support for the first-ever Black lesbian narrative feature, Dunye turned to her community as a resource.

“The Watermelon Woman – for me, was really about community; the community that made me Cheryl – as the maker to make that, as well as the narrative community,” Dunye told INTO. “So, Incorporating folks like Toshi Reagon, Sarah Schulman, Cheryl Clarke – those were people that were my elders that I looked up to – or collaborators, or people who were in my community, and I wanted to make sure that we put our people in.”

With deliberate intent, Dunye hand-picked people from her private and professional circles to cast the film’s characters. She also cast figures that have now established themselves as cultural icons: critic Camille Paglia, music legend Toshi Reagon, historian Sarah Schulman, and feminist activist Cheryl Clarke. Dunye also enlisted the help of local legends like Suzi Nash, Julie Tolentino Wood, and Jocelyn Taylor. Earning a spot in the film’s end credits, Nash hosted karaoke every Thursday night at Philly’s own lesbian bar Sisters for 16 years. Years earlier, in 1990, Wood and Taylor worked together to create community for lesbians of color at the CLIT Club in NYC.

When fictionalized characters are paired with the familiar faces and real places of Dunye’s life, her “faux” documentary about the fictionalized “Watermelon Woman” becomes a different kind of documentary, one capturing the experiences of the Black lesbian studs who lived and loved in the Philly of the 1990s. Under Dunye’s direction, the camera rolled and archived simultaneously. Following the success of The Watermelon Woman, its entry into The Criterion Collection and hindsight’s 20/20 vision, Cheryl Dunye now stands in favor of playing the very hand that she was once forcibly dealt. “Make your own Hollywood,” she says. “Populate your film with your world and who you are and make that the star.”

Related:

Anita Cornwell Wrote About Black Queer Women with Heart, Rage, and Brilliant Honesty

“Black Lesbian in White America” should be back in print this instant.

As much as The Watermelon Woman is situated in the realm of Dunye’s reality, she affirms that the film is much more interested in the power of storytelling than in any one individual’s story. “This was happening before me,” she explains, “you’re just seeing it in a different container and lens.” Much like the viewer themselves, these characters are going about their days by living in ways that are uniquely normal to them. The only thing that appears to fictionalize these systemically overlooked characters is the presence of Dunye’s camera lens; by that understanding, the underlying message is made available to any and all who watch The Watermelon Woman. No matter what others tell you, Cheryl Dunye says, “You are archivable.”

“You should make your own archives,” Cheryl urges in the film—and for good reason. In discovering the true identity of Fae Richards as a sapphic sister and Philly nightlife legend—one who “used to sing for all of us stone butches,” the protagonist brings truth to Fae’s complex legacy. Amidst capturing Philly landscapes and sapphic activities, Cheryl Dunye did the same by daring to share her reality as a Black lesbian to viewers, creating her own legacy in the process.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox