For those not in the know, this year has ushered in over 350 anti-trans bills across the U.S., many of them focusing on excluding trans girls from school sports and attempting to gatekeep life-saving gender-affirming care from minors, regardless of parental support. The worst of these focus on what the right calls “gender ideology,” and paints trans adults and allies as “groomers” who are desperate to turn otherwise perfectly fine cis, straight children into transsexual perverts like us. In states like Texas and Florida, supportive parents of trans youth, as well as doctors who agree to provide gender-affirming care, have also come under fire. And now, as expected, they’re coming for trans adults, not just children.

This is all to say that I’ve spent a lot of time this year thinking about how children—not as individuals, but as a broad concept—are used as pawns in very petty adult games in this country’s politics. In a sense this has always been so, but we’ve seen it ramp up in regard to queer and trans issues. The fear, on the part of the religious and conservative right, is that children are malleable creatures who can be persuaded to become whatever identity they’d like, including a queer identity. Which, if you know anything about humanity, isn’t how it works. It’s true that more people are identifying as queer and gender-expansive than ever before, but it’s not because we’re telling them to. It’s because it’s an option now. It’s broadly possible now to be a trans person in a way it’s never been before in history. And that’s exciting, but it also puts a target on our backs.

That’s why I wanted to watch Night of the Hunter again, one of the finest films ever made about the way children are used as political pawns, when the people using them are only really trying to hurt them.

The film was adapted from Davis Grubb’s book of the same name from two years earlier. It was a classic Midwestern gothic tale—the Brothers Grimm by way of Shirley Jackson—about a phony preacher who marries rich widows and then kills them off, disgusted by female sexuality and able to charm anyone he meets. The film was pitched to the great actor Charles Laughton, who’d been known, up to that point, for his celebrated physical performances as Great Men (and little shits) of history. In 1933, he played Henry VIII in Alexander Korda’s The Private Lives of Henry VIII. Later, he starred opposite Gertrude Laurence to play the title role in Rembrandt. By 1935, he’d taken on perhaps the Hollywood role he’s still best known for, as Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty, and then, a few years later, played his other best-known role despite the fact that it has almost no speaking lines: the bellringer Quasimodo of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Night of the Hunter is one of the finest films ever made about the way children are used as political pawns, when the people using them are only really trying to hurt them.

After the 1930s, Laughton’s moment of being sought-after would largely end, partly due to the fact that the historical films he’d made his name doing had fallen out of fashion by the 40s and 50s. He’d have a resurgence in the 50s and 60s, taking on some of his greatest (and campiest) roles in Spartacus, Advise and Consent, and the fantastic Witness for the Prosecution. But before that, he made Night of the Hunter. It was the only film he ever directed, and despite being accepted as one of the most original and truly auteurist achievements Hollywood ever put out, he chose not to follow it up. And there were a few reasons for this.

Laughton was famously gay, and although probably everyone knew it, he lived his life in terror of being exposed. He married another gay artist in Hollywood, the iconic Elsa Lanchester, and together they protected themselves from scrutiny by appearing, to everyone who didn’t care to look too closely, the perfect character actor couple: people a little too weird-looking to be celebrities, but who enjoyed that status anyway.

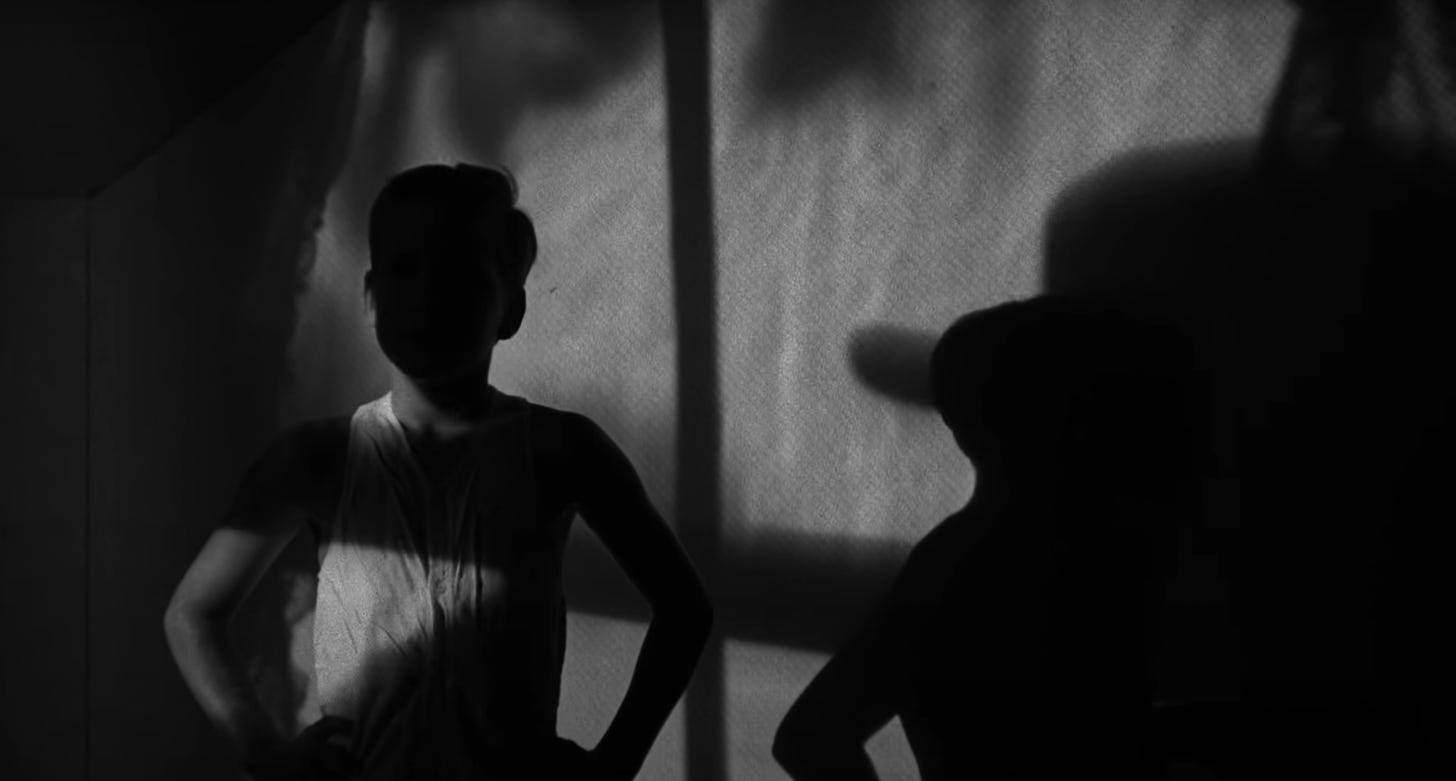

From the first moments of Night of the Hunter, you know that this was a film that could only have been made by a gay man. Reverand Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) sits in the audience at a sleazy strip club, watching a woman gyrate and clenching his fists, famously tattooed with the words “hate” and “love” on his fingers.

His jackknife rips through his pocket in a not-so-subtle ejaculation: this is a man who hates women, who hates specifically what they do to men sexually. It doesn’t seem to be repressed desire, either, just hatred, plain and simple. He’s made up his mind to punish women, and that’s just what he’ll do. The Christian society around him makes it, after all, supremely easy.

All the preacher has to do is enter a small, god-fearing town in order to essentially take possession of it. Mitchum’s performance, in fact, seems to owe a lot to Chaplin’s decades before, in another phony-preacher narrative, 1923’s The Pilgrim. But Powell is a sight more sinster. No sooner does he show up than he’s embraced wholeheartedly, despite being every inch the faker. It’s something we can see, of course, from the start. But we’ve also been let in on his scheme, per a monologue in the film’s first scene. He’s made up his own version of religion, he explains as he talks aloud to God, one that fully exempts him from the crimes of murder and robbery. When Powell gets arrested for stealing a car, he meets Ben Harper, a murderer in his own right, having just stolen $10,000 in a bank robbery. But he’s on death row, and Powell isn’t.

It’s the innocents who stand as the keeper of the story’s guiltiest secret.

Because it’s the kids that know where it is, and the brilliance of the film—on a structural level—is that it’s the innocents who stand as the keeper of the story’s guiltiest secret.

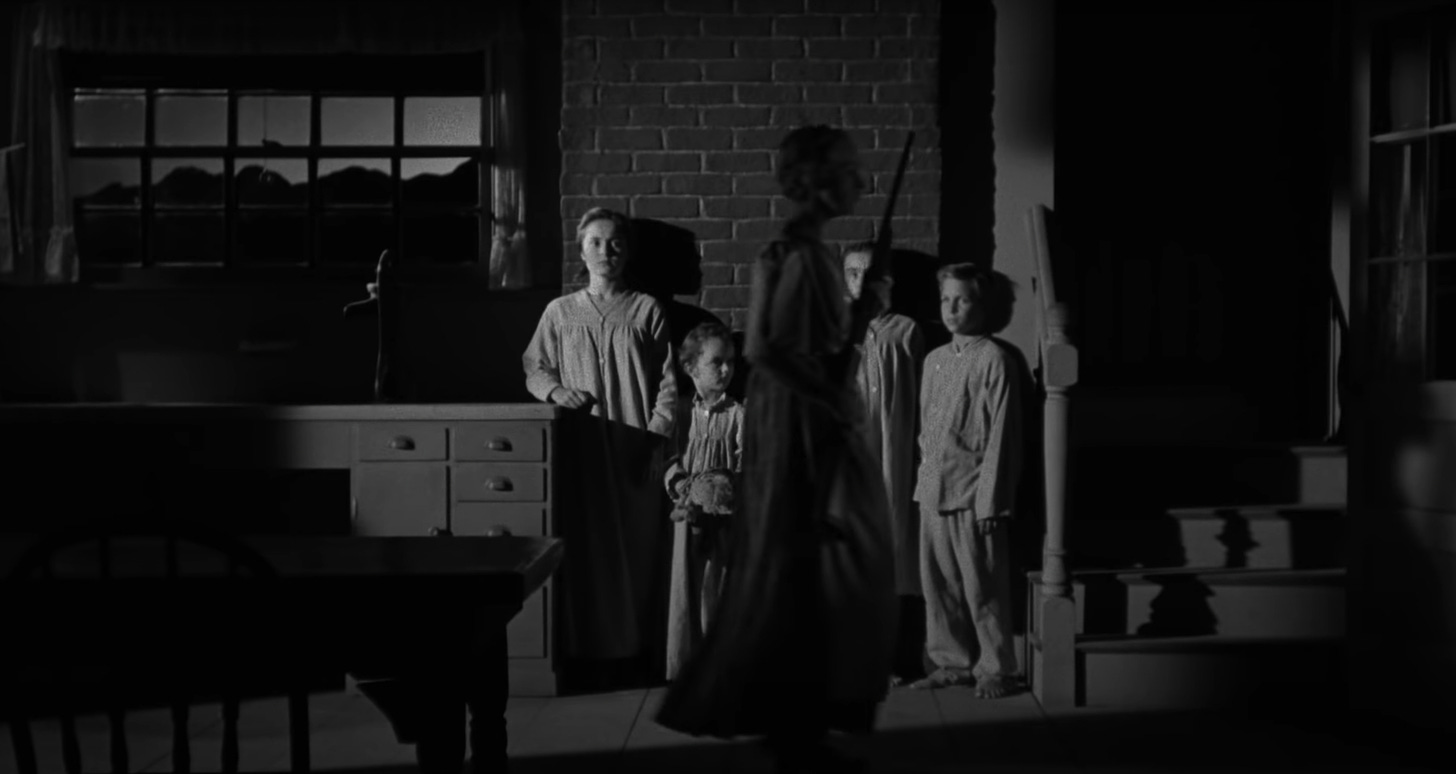

When we meet John Harper, the 7-year-old son of Ben, he’s witnessing his father get arrested. It’s one of the most wrenching parts of the movie, and it happens early. The camera cuts between Ben being cuffed by the police and John shouting “no,” trying his best to rise and meet the extremely adult situation despite being, as those pained “nos” remind us, very much a child. From that point on, it’s up to John to protect his family, which first consists of himself, his younger sister Pearl, and his mother. But after Powell (with the help of the Widow Harper’s extremely nosey employer, Icey Spoon) convinces Willa to marry him, he quickly murders her after realizing that she doesn’t know where Ben’s money is hidden. We don’t see the murder, but we see the corpse, in what remains one of the film’s most haunting shots. If you’ve seen Night of the Hunter, it’s this image you’re likely to remember, along with the image of Lillian Gish in profile, shotgun in lap, protecting her flock.

Powell’s story is that Willa ran off to be with another man, leaving him in charge of the two now good-as-orphaned children. But the minute he’s alone with John and Pearl, he’s asking where the money is. The kids make their getaway via a rowboat and crawl down the Ohio river, finally falling into the good graces of Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), an older woman raising a full flock of unwanted children. John and Pearl fit right in. But of course it’s only a matter of time before the unsleeping, seemingly unblinking Powell finds them out, stalks them, and tries to take the money back for the last time. Before that time, Powell tried to pit the children against each other to find the money, the thing which can mean nothing to them. “John doesn’t matter,” Powell shouts at John’s sister. But what he means is that John is powerless: and these are two very different things.

It’s not your average 1950s film, and you can see that from the very beginning: it’s in the bizarre, confusing use of music, the floating heads of children that greet us from the first frame: this is a fairy tale, and the way it’s filmed is in keeping with the darkness and strange theatricality of how a frightened child might see the world. The film was made with constraints in mind—one senses Laughton wanted it that way, even if he could have wrangled a bigger budget. Flooded sound stages transform into the long stretch of Ohio River the children flee on, leaving only a hint of that phoniness with us, just enough to remind us that this is an impressionistic, as well as an expressionistic, view of the midwest, of small-town life, of Americana itself. We see the deep, high shadows and ominous cracking twigs outside the house as a child might see and hear such things. Because Night of the Hunter understands what it’s like to be a child: perhaps it was that Laughton hadn’t forgotten the terror of those years. Perhaps it was that he couldn’t forget.

But perhaps it’s even deeper than that. Laughton’s identification with the children of the film feels, to me, more potent than usual. Because it’s not just a film about children: it’s about the role children play in society, how they are used, how they become symbols at the expense of their actual humanity. How they are by turns ignored and paid too close attention to. And how, politically, their defense comes to stand as the reasoning for so many heinous acts that they, themselves, have nothing to do with.

The fear on the part of conservatives is that learning about transness is the same thing as indoctrination.

This is the position queer people are put in time and again. We are treated like bad children, and we are framed as the corrupting forces that society must protect children from, if the human race is to continue. It started, perhaps, with the seminal 1961 anti-gay propaganda film “Boys Beware,” in which gay men are shown as predators waiting outside the bushes of grammar schools waiting to pounce on young boys. When gay marriage was close to being passed in 2007, you’d see the same kind of propaganda everywhere, the image of two muscle-bound men gripping the hand of a young boy, as if to say, “if you let these gays adopt kids you’re basically endorsing pedophilia.” And now, of course, it’s back, with the accusations of “groomer” and “pedophile” following every major gay and trans Twitter account. This year has seen a coordinated attack not just on gender-questioning kids, but on the concept of education itself. The fear on the part of conservatives is that learning about transness is the same thing as indoctrination. And the assumption within that—as it has always been—is that children are essentially stupid creatures, malleable and porous and unable to simply hear about an identity or orientation existing without turning into that thing on the spot.

But children, as this film understands, are smart, and not just in the corny way the “Family Circle” comics would have us believe. More than wise, they are savvy: they are brutally tuned into the horrors of the world, which seem all the more horrifying to them because they lack explanation. They are keen judges of character, and as for phoniness, I probably don’t have to tell you that they can smell it a mile away.

It’s the children who see Powell for what he is: an egregious fake. The entire town might be fooled, but John and Pearl Harper are not. Neither is Rachel Cooper, as played by Lillian Gish, the incredible silent film actress who made her career playing the same type of wide-eyed, innocent-yet-wise orphans that John and Pearl are. She sees through Powell’s quavering preacher’s delivery, his selected biblical incantations, as cherry-picked as every conservative pundit preaching about what the Bible deems sinful and not. The duet they share, “Leanin’”, is a telling moment: not just because they both know the words to the hymn despite being on opposite sides of the moral scale, but as if to point out that the most important thing about religion isn’t its teaching about good and evil, but its ability to be interpreted differently by people who share a faith upon whose true meaning they cannot agree.

There’s the sense of Gish as Rachel Cooper being the world’s oldest child, a woman who loves the idea of childhood so much that she’s given her life to protect its sanctity. Her favorite incantation, in fact, is the opposite of what Powell preaches. It’s not a flashy quote about Cain and Abel and love and hate and sin. In fact it’s not a Bible verse at all, but a statement: “Lord save the little children, for they endure, and they abide.”

When critics saw Night of the Hunter, they were mostly unimpressed. They saw the film as old fashioned, with its cardboard backgrounds and expressionistic shots reminiscent of the Germans, its sometimes cartoonish poses and camera tricks. They didn’t like, either, the fact that Laughton shot the film in the style often used in the silent era, a style that produced more naturalistic takes by running the camera until the film reel was used up. It produces something of a stiltedness in the acting, which is already wonderfully overblown. But that’s the point: once again, it’s a fairy tale, via the Bible, with a touch of the Gothic built in. It had to look the way it did, and move the way it did, with a falseness that some critics could only see as false, rather than the obvious, studied hand of a director who wanted to tell the story through the eyes of the children, who are in fight-or-flight mode for nearly the entire film.

Laughton was so discouraged by the reception to the film that he never made another. The experience broke his heart. He’d made a perfect movie that nobody had the vision the actually see for what it was. Perhaps something about it was too childlike, too faithful to that way of seeing things as a kid, too honest, in some ways—specifically too honest about hypocrisy—for adults to really take in.

It reminds me of another story about children, from another author who never made another work of art1. Harper Lee’s 1960 novel—made into the 1962 film—To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s one of the only other stories I can think of that takes a child’s sense of the world seriously, reducing the complexity of society to a handful of boogeymen and good men eternally facing off.

But there’s a kind of redemption at the end of that story—there is for the white people, at least. You’re able to read that book, and watch that film, without the same sense of terror and mystery about human relationships. At the end, even the terrifying figure of Boo Radley has revealed himself to be essentially kindhearted, while the film’s true boogeymen—the racist, incestuous Ewell family, and the jury that believes them—are made to seem more ignorant than evil.

Night of the Hunter doesn’t let us off the hook so easy. It’s a movie that knows how evil doesn’t rest. It’s a movie that understands, essentially, what the human experience can be boiled down to, in a pinch. It’s in Rachel Cooper’s final line about the little children. That they endure, and they abide, which is all life actually is. When we talk about the human spirit, it’s this aspect we’re talking about. The almost superhuman, yet utterly boring ability to endure.

Because that is what we do in the face of evil, and it’s what we’ll continue to do. We will endure, and we will abide, and we will watch, and we will wait. And we will always keep score.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox