Throughout the latter part of the 20th century, some gay men living in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) were stabbed, strangled, bludgeoned, shot, and sexually assaulted without anyone thoroughly investigating their deaths, let alone punishing a perpetrator for them.

Now these cases, which were often declared suicides or robberies gone wrong, are the target of new research that seeks to classify these crimes as gay-hate and bring justice to the victims.

The most prominent case to make the media rounds is probably the killing of Scott Johnson, a mathematician from the United States who was pursuing his doctorate in Sydney and who was killed in 1988. His family spearheaded several inquests into his death and after the third, the coroner ruled the death a homicide.

Johnson’s family’s push for answers led to more questions about what exactly happened in NSW and why police did not put the pieces together that there was an epidemic of violence against the gay community, says Michael Atkinson, Program Manager for Safety, Inclusion and Historical Justice at ACON, a LGBTQ rights nonprofit that released a report on the murders.

The inquests into Johnson’s death as well as other lobbying efforts by the families and friends of other victims spurred ACON to take on the massive research project of investigating a list curated by two police officials of 88 suspected anti-gay homicides that occurred between 1976 and 2000.

“We were really concerned about that number,” Atkinson tells INTO. “New South Wales agreed to conduct a police investigation into those alleged 88 cases to determine if there was bias. ACON felt the importance of a community voice in the conversation, so we did our own review on those 88 cases.”

The organization gathered a team of researchers to go through public files, judgments and media reports and realized that the “epidemic of violence” in Australia was underreported and that people were not engaging with police for fear of being outed, Atkinson says.

People didn’t trust the authorities because their names were being leaked to newspapers. “People didn’t even go to hospitals to receive medical help, even for long-term mental and emotional injuries,” he said.

This is why the list of those murdered and affected by the anti-gay violence was inconclusive. The 88 cases were collected without police records, as those were unavailable or sealed.

After ACON’s report, The New South Wales (NSW) Police Force in Australia released their own report in late June after assembling a team called Strike Force Parrabell that began reviewing the deaths in 2015.

Out of the list of 88, the police reviewed 86. In the 63 cases that were solved, eight were found to be bias crimes and 14 were suspected bias crimes. The authorities found no evidence of bias crime in 30 of the cases, while they couldn’t determine the motivation in 10.

In those that were solved, 84 people were charged with murder, nine with manslaughter, and three with other crimes. Ninety-six people were charged overall.

Authorities admit that many of the cases saw the charge of murder reduced, including 15 that used the so-called gay panic argument which allowed defendants to claim temporary insanity caused by their perception that the LGBTQ person was making sexual advances on them.

Strike Force Parrabell found that in 65 cases the assailant was heterosexual and the rest were or were believed to be gay or bisexual.

Twenty-three of the cases remain unsolved.

“While not perfectly documented, violence against the LGBTQI community is a well-known blight on human history, not just in NSW – or even Australia – it is a not-so-secret shame for the entire world,” Assistant Commissioner Tony Crandell, who oversaw the team of investigators, said in a statement.

Although the past can not be changed, the review was undertaken in order to “to acknowledge what has happened and make sure it can’t happen again,” he added.

“It’s an ugly part of our history – it needs to be acknowledged – and we need to do everything we can to make sure no one is ever again fearful for their life because of who they are,” he added.

In their statement, NSW authorities said that they did not uncover overt anti-gay bias from the police but that the relationship between the LGBTQ population and police was problematic and that investigations were not sometimes conducted thoroughly.

“Historically, police and the LGBTQI community had quite a tumultuous relationship,” Crandell claimed. “But in recent times, we have progressed in leaps and bounds … I acknowledge an absolute requirement to never let history repeat,” he added, stopping short of apologizing on behalf of the police.

The lack of apology is disappointing to ACON and to many stakeholders.

“We were disappointed that it didn’t go far enough,” says Atkinson.

He believes there should be an independent review of police handling of the cases since the Parrabell report was internal. ACON also recommended that authorities begin paying special attention to potential hate crimes.

ACON also received flack for their report. “People also think we didn’t go far enough, specifically in relation to the police and the judiciary, but that wasn’t part of our process,” Atkinson explains.

Other recommendations included awareness on hate crime. When investigating a crime like murder, police should note the possibility that it was a hate crime. “If you consider hate as a motive for murder,” Atkinson explains to INTO, “you will find different data, different information which could lead you to the perpetrator and allow for justice.”

He adds that ACON still appreciates the work the NSW police did in the report and the continued collaboration with the LGBTQ population. “Violence is just not an option. It’s not acceptable,” regardless of homophobia, transphobia, intersexphobia, or biphobia, he says.

Three decades of violence without much government accountability seems quite ludicrous today, but Australia had a “nasty, secret underside,” says Frank Bongiorno, a professor of history at Australian National University and author of The Sex Lives of Australians: A History.

“The gay rights movement emerged in Australia in the late 1960s, but the environment was still unfavorable,” he explains. The government, including the police, was complicit in maintaining negative attitudes toward gay men.

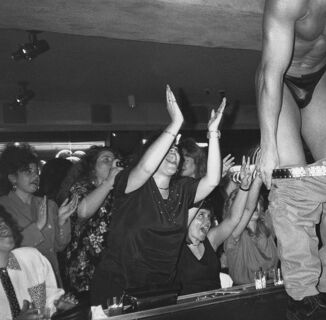

“It’s clear that there was anti-gay bias within the police force by looking at the New South Wales police force and the gay Mardi Gras events. The first in 1978 was supposed to commemorate Stonewall in the U.S. but eventually led to many arrests,” says Bongiorno.

Police corruption in the 1970s also played a part in how these crimes were handled, he suggests.

Decriminalization and the overall trend of becoming more accepting of different sexual orientations happened gradually. In fact, explains Bongiorno, it was a suspected police bashing that led to decriminalization of homosexuality in Australia.

In 1972, police in the state of South Australia were suspected of killing George Duncan, a law professor at the University of Adelaide who was gay. The crime sickened Australian society and catalyzed decriminalization.

Since then, things have changed enormously, he says. One of the changes is the inclusion of vulnerable groups in policing efforts.

“If there is to be adequate policing around this violence,” he says, “police have to work with the relevant communities.”

But why was there such violent homophobia back then?

“Australia has harbored some very traditional forms of masculinity that have roots in sexual bravado and aggression,” Bongiorno explains. “There is a homophobic dimension as well. The real [Australian] man is an aggressively heterosexual man.”

Though the pain from these murders can still be felt by those who knew the victims and especially those who may never know why their loved one was killed, both the Strike Force and ACON are hoping for a chance to remember those who were lost due to this perception of masculinity.

To honor the victims of the killings, ACON was granted permission from the local council at Bondi Beach in Sydney to erect a monument in an area where there is already a walking tour detailing the lives of some of the men killed in the area during this time.

“We aim to have that monument be a figure, something that holds value in the community, nationally and internationally…in order to pay honor to the atrocities that happened and continue to happen today,” Atkinson said.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox