Mia Martinez feels like a phoenix about to be reborn from the ashes.

Speaking over the phone from a facility near Chicago, Martinez chronicled her journey that begins in 1995 as a cisgender man entering prison, becoming a Muslim, discovering her gender identity, transitioning from male to female and now looking at an upcoming release date.

“I spent many years here confused and angry,” Martinez told INTO in a recent interview as she prepared herself for freedom. And what’s making this even sweeter is that when released in early 2018, she will walk into the arms of her communityone that she didn’t know before she found herself.

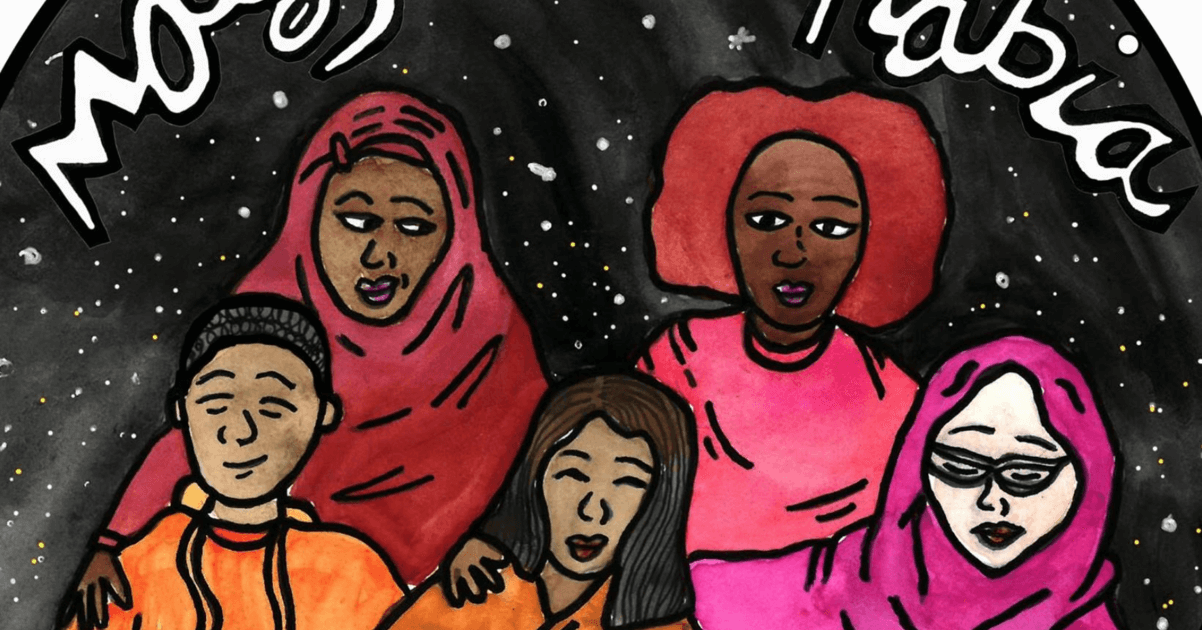

Thanks to the work of a small number of volunteers for Masjid al-Rabia, a women-centered, LGBTQIA affirming mosque in Chicago that organized in 2016 after the Pulse nightclub shooting, support for people like Martinez has been able to transcend any prison walls.

Through their tireless work, they’ve been able to create lifeline to incarcerated LGBTQIA Muslims folks like Martinez who are often isolated from their spiritual communities in prison because of their sexual orientation or gender identity has been created.

“For me, it’s been clear that this is a part of our community that’s at risk of being forgotten entirely,” said Mahdia Lynn, the director of Masjid al-Rabia.

In its first year, Masjid al-Rabia launched a program to connect with incarcerated LGBTQIA Muslims. Partnering with Black and Pink, an organization that broadly supports incarcerated LGBTQIA people, Lynn and Masjid al-Rabia put out a call for interested community members to send letters to the mosque’s P.O. box in Chicago. That was in May 2017.

“I remember, the key kind of stuck,” Lynn recalled when she went to open the mosque’s mailbox after sending out the nationwide call for letters. “And it opened, and it was stuffed, bottom to top [with letters], and compressed. It was exciting and horrifying. And the next week, it was the same.”

In a matter of months, more than 400 incarcerated peoplewho presumably identify as LGBTQIA and Muslimhave sent letters to Masjid al-Rabia, looking for one simple thing: to know that they’re not alone. The mosque has responded by organizing a penpal campaign in more than a dozen cities. They’ve named the program the Black and Pink Crescent.

“It’s affirming to know that these two identities can exist together,” said Cruz June Rodriguez, who is part of Masjid al-Rabia’s leadership team. “You can be LGBTQIA and religious.”

“It’s not a unidirectional program,” Lynn said. “[The volunteers] are overwhelmingly LGBTQIA Muslims, who are on the free side of this equation. It is in service to one part of our community, but it involves the entire community.”

Rodriguez reflected on his own experience as a queer Muslim, recalling moments like breaking his fast during Ramadan alone. Now, as part of Masjid al-Rabia’s work, he helps send Ramadan care packages to incarcerated LGBTQIA Muslims across the country.

“It’s kind of like we’re breaking fast with them,” Rodriguez said. “Even if we’re all celebrating alone, we’re celebrating together.”

“For me, it’s been clear that this is a part of our community that’s at risk of being forgotten entirely.”

But it’s not just celebration but most importantly it’s a form of acceptance that many have never experienced before.

“This is the first time they’re talking to someone who will not shame themjust for someone to hear them and be able to relate a little bit,” he continued. “ It reminds me of when I felt validated as a queer Muslim, and how amazing that was.”

And for Rodriguez this in-turn allows these incarcerated folks to feel at ‘home’ in themselves for potentially the first time.

“What they’ve managed to do is give people who don’t feel accepted,” Martinez said about Rodriguez and Lynn, “they’ve given them a place in their hearts and minds to say, ‘I’m at home right now.’ As a Muslim, I’ve probably felt the most acceptance [now] than I’ve ever had in my entire life.”

A look at the other hundreds of letters reveals similar stories from prisons across the country. Those who have written the mosque tell of being excluded from Muslim communities in prison for their sexual orientation or gender identity”banished,” one letter said. The letters represent a cross-section of the LGBTQIA community and come from people of all ages and backgrounds.

“It’s been very much a blessing, these first couple months,” Lynn said about the rapid growth of the pen pal program. “It was small enough that it could just be me, then suddenly we were getting lots of letters each month. It was sink or swim for a while. Everything we’ve done is completely unplanned and completely learn by doing, and we’ve gotten good at it.”

As for Mia Martinez, she hopes to join the ranks of Masjid al-Rabia’s volunteers as soon as she’s released from prison, likely in early 2018.

“I’m going to spend some time with Mahdia and the gang and see what I can do in the community,” Martinez said after reflecting on her journey from and how this organization has not only saved her, but changed her for the better.

“It’s been my platform in recent years to try and help other people avoid some of the pitfalls that I fell into [and] showing them there’s a better way.”

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox