Flame Monroe’s inclusion in Phat Tuesday: The Era of Hip-Hop Comedy represents a long-overdue—yet not entirely unproblematic—portrayal of the role of queer people of color in comedy. Mainstream comedy has been dominated by cisgender men who, intentionally or not, use othering as a driving force behind jokes. The highlight of women of color comics in the third part of Phat Tuesday, then, would seem to offer a sign of change in the industry. Comics such as Luenell and Kym Whitley found comedy fame in the 90s performing on Tuesday nights at one of the few places that welcomed Black women comics to the stage. But while this recognition is important, Flame Monroe’s inclusion as a transfeminine comic of color is not without its complications.

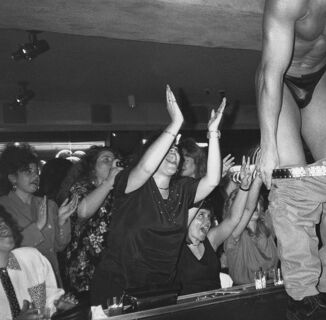

The Amazon Prime series Phat Tuesday: The Era of Hip Hop Comedy details in three parts how Black comedy existed during a time when the comedy establishment—clubs, TV, and movies—were dominated by white, cisgender men. In 1985, Robin Harris, best known for his creation of Bèbè Kids and his roles in Do the Right Thing and House Party, started Comedy Act Theater with the “Godfather of Comedy” Michael Williams in Inglewood, CA. This space became a haven for Black comics in the mid ’80s to work out material and entertain crowds of Black audiences. It was one of the first of its kind: the club shut down after the LA Riots but was resurrected by Guy Torrey (American X) in the form of Phat Tuesday, a once-a-week event highlighting Black comics at the legendary Comedy Store in Los Angeles. The spirit of the Comedy Act Theater was reimagined and expanded in Phat Tuesday, soon packing the Comedy Store to the rafters a bringing in a bigger audience than on any other night. On this new stage, comics like Mo’Nique, Leslie Jones, and Tiffany Haddish made their debut. It was here, alongside her peers, that Flame Monroe began to make a household name for herself as a comic who happened to be trans.

Mainstream comedy has been dominated by cisgender men who, intentionally or not, use othering as a driving force behind jokes.

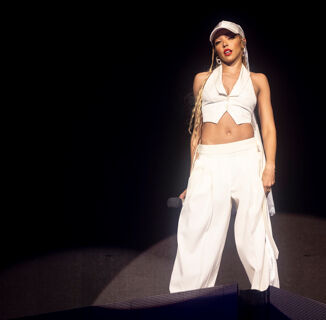

Monroe began performing in an era of queer-blaming, not to mention queer-bashing. Her inclusion in the comedy line-up of the 90s and her inclusion in a doc about Black comedy is no doubt a representational win for trans people and trans women of color. A past photo of the comedian is featured, her blonde hair coiffed towards the heavens, ready to take on anybody’s stage. In Phat Tuesday: The Era of Hip Hop Comedy, Flame Monroe speaks on how Guy Torrey provided an opportunity for queer comics to perform as themselves. With this opportunity, Flame regularly took to the Phat Tuesday stage to do routines that confronted audiences with comedic concepts of gender and queerness in the ’90s, as she spoke candidly about her biological children and having a family as a trans woman during a time when the HIV/AIDS epidemic gave rise to gay plague panic.

While Flame Monroe’s spotlight in Phat Tuesday: The Era of Hip Hop Comedy has given the underrepresented comic a new platform, she also has voiced her support of Dave Chappelle and his performance in The Closer, which was met with widespread criticism for his support of TERFs. Like Monroe, some trans people have come to Chapelle’s defense, but few who hold true celebrity status. Speaking with Out, Monroe said of Chapelle and the special that it was, “was nothing but fact. There is a pecking order in the LGBT community because a gay white man in America is still a white man in America.” And yes, while Monroe’s assessment of “pecking order” in America is very true, she still fails to address Chapelle’s alignment with TERFs. In effect, her silence overlooks the harm caused by Chappelle’s derogatory statements aimed towards her own trans community.

Some may wonder how a comic like Flame Monroe could exist: How can someone who identifies as trans be recognized for her comedic contributions and also stand in defense of someone like Chapelle?

The answer may lie somewhere in Phat Tuesdays: The Era of Hip Hop Comedy and the context of the era. Phat Tuesdays occurred during the ’90s: the time of Jerry Springer, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and the gay community throwing parades at the mere mention of a gay character in popular TV. Guy Torrey says that, in that climate, inviting Flame Monroe to the stage “got eye rolls’’ from other comedians. In that world, she made a name for herself in front of a mostly-straight audience with built-in prejudices against queer people, made concrete through the often-stereotypical queer representation in the media of the time. During this moment in her career, Monroe had to navigate straight spaces as a queer person. Like many people who exist in the intersection of queer and Black, Monroe had to negotiate how to present herself to an audience of straight peers within the political and cultural climate of the 90s.

How can a comic who identifies as trans be recognized for her contributions and also stand in defense of someone like Chapelle?

Self-deprecation is a specialty of Monroe’s, with her regular idolization of heteronomative beauty standards and glorification of DL (down-low) culture. In the same set, she will speak about her life as a trans woman, raising kids as a Dad, and dressing up for comedy. She took stories of her queer life and turned them into her bread and butter. Some may see Monroe’s jokes as turning queer othering on its head by using oneself as the punchline to get ahead. This tactic has found traction and has landed her stand-up spotlights on Netflix and HBO. “I wasn’t believable enough,” she says, referring to herself not presenting as “woman” enough: a regular confession in Monroe’s act. But statements like this are problematic in the immediate sense and dangerous in the long term, potentially more so than even Chapelle’s: A trans woman confirming hetero-biased standards to an ill-informed audience is tone-deaf to the current and real struggles of all trans women. The damage is made even worse when other trans women hear these words from someone in the community who actually has a platform. The destruction is multiplied as these statements are regurgitated show after show to audiences far removed from the real-life violence against trans people. It gives people like Chapelle license to continue to alienate and use queer and trans people and our lives as a setup to a punchline. As these factors work in concert, it further reinforces that it is okay to stigmatize queer people in everyday life.

Monroe’s story is one of survival, and in some ways, she has triumphed. She figured out a way to make straight people laugh during times of queer representation blackout. She learned how to be the “the right amount of queer” to appeal to her audience and peers through the years, and has found some financial success through that. But while her national platform is still growing, Monroe may soon asked just how far she is willing to align with the othering of queer people in her comedy routines and peers. Flame Monroe may face the choice of revamping her routine towards a more nuanced commentary on the queer experience, or continuing to debate her own personhood as the punchline.♦

Zuri C. Davenport is a transdude of the Souf. Nature and Sci-Fi enthusiast at the intersection of Black, Queer and Bibliophile. Follow them on Twitter.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox