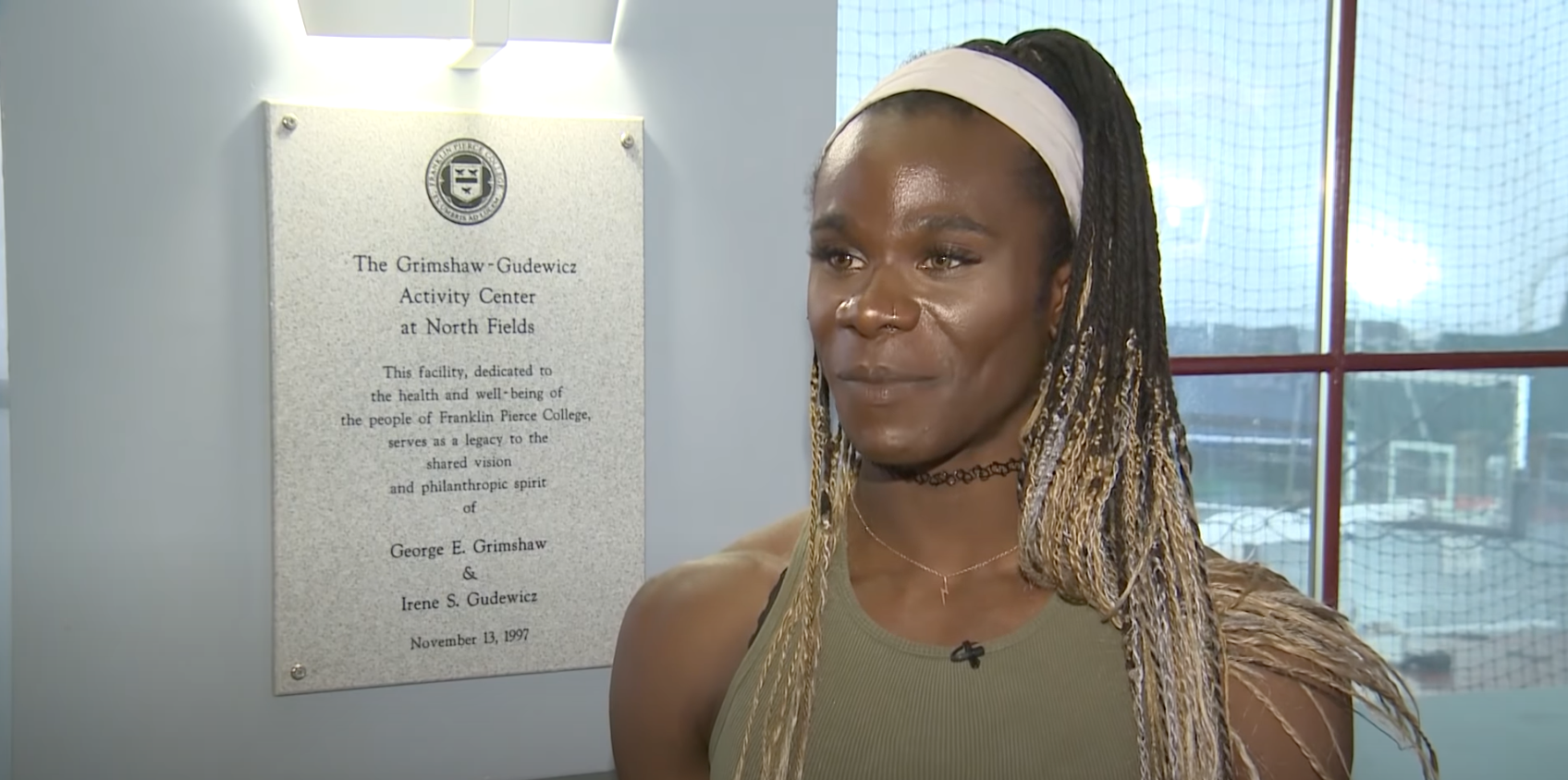

CeCé Telfer, recently profiled in the New York Times, has joined the growing number of trans athletes training to compete in the Tokyo Olympics. In 2019, she became the first openly transgender woman to win an NCAA championship. Now, despite the setbacks of the COVID-19 pandemic, she is determined to participate in the Olympic 400 meter hurdles. “When I open my eyes,” she told the Times, “all I can see is the Olympic trials.”

Before she can get close to those Olympic hurdles, there are a number of others in her way. She must first qualify for the U.S. Olympic trials by finishing a race in under 56.5 seconds (the NCAA has her record to date at 57.53). Once she gets there, she must finish in the top three in order to pass the national trials.

Trans athletes already encounter a number of obstacles when participating in sports. Olympic regulations require that transgender women suppress their testosterone levels for at least a year, which CeCé has been doing since 2017. Regardless, she has faced an endless stream of complaints from parents ever since she began competing in women’s collegiate sports in 2018. She has also received death threats online, and one of the coaches she contacted for training stopped responding after discovering that she was transgender.

As if this wasn’t enough, the COVID-19 lockdown has made proper training facilities and coaches scarce. CeCé has been forced to make do on rural roads and a high school track field two hours drive away. For two years, she coached herself, but with the Olympics looming, she reached out as far and wide as she could. The only coach she could find was located in Mexico. Committed to her Olympic vision, CeCé gave up her apartment and her job in order to relocate to Mexico for training. This, however, did not last long: CeCé is also an immigrant, having grown up largely in Jamaica and Canada, and had to return abruptly to the US to finalize her citizenship. Now without income or a place to stay, CeCé couch-surfed and lived out of her car for two weeks. Eventually, Nicole Newell, the director of counseling at her alma mater, offered CeCé shelter after discovering how she had been living. Newell quickly found herself in awe of CeCé’s resilience, as she told the Times: “No matter what comes at her, she just keeps moving.”

Growing up, CeCé hid her true gender from her single mother. When she came out three years ago, her mother told her that she would never see her family again. She began her athletic career at Franklin Pierce University in 2016 competing in men’s teams despite publicly identifying as a woman. In 2017, she withdrew from sports in response to the treatment and looks she got from other athletes.

When she made the decision to return in 2018, she encountered the last thing she expected: kindness. At the coach’s office, she requested that she be allowed to compete with other women. His response: “Finally.” While CeCé burst into tears, he went on to state unequivocally, “You can compete as CeCé, as yourself, as a girl.”

Now having won the NCAA title at the Division II outdoor track and field championships in 2019, Telfer is looking to carry the momentum forward into Tokyo. To date, no openly trans athletes have ever participated in the Olympics. This year, there are currently 8 other trans athletes training to compete in the Summer Olympic and Paralympic games. Among them, Laurel Hubbard has already qualified.

This progress comes at a time when trans athletes, particularly minors, are being targeted with laws restricting their access to sports in several US states, most recently in Tennessee and Texas. Rather than let this opposition intimidate her, CeCé Telfer recognizes that her Olympic aspirations are so much bigger than her. “It’s important for me to do it for these kids,” she told the Times. “It’s important for me to do it for my people—whether it be women, Black people, transgender people, LGBTQ people—anybody who is scrutinized and oppressed.”

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox