This article discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), text “STRENGTH” to the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 or go to suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

When André Leon Talley died last week, I was one of several people to pour out how much he did for Black people, queer people, and those who didn’t fit into societal norms, especially in the world of fashion. Talley’s undeniable style expertise and knowledge received much of its well-deserved recognition and praise. But there’s something else that Talley deserves recognition and praise for: navigating and surviving in the media industry.

Before and up until Talley’s death, most of what people cared to know about him revolved around either how much money he had, or didn’t have, or ever get; his love live, or lack thereof; his experiences with discrimination; and Anna Wintour (all not mutually exclusive from each other). If you look at the reviews for his novel The Chiffon Trenches, his second memoir, most of the negative ones complain about the lack of words addressing these things — which may be a legitimate criticism in some way, but not a fair basis for debasing the memoir altogether.

Similarly, after the immediate shock of his death wore off, much of the public remembrance of his legacy revolved around those very same things: the money he should’ve had or gotten; the love he deserved but never got; the discrimination he experienced… and Anna Wintour. While they were likely well-intentioned, the number of people suggesting that the Met Gala — chaired by Wintour and organized by Vogue in benefit of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute — should either dedicate this year’s ceremonies to him, or theme them after his work and legacy, or rename something in his honor.

“There are simply too many different examples to describe the way in how non-white people, especially Black people, are rarely allowed to be themselves, to be human, to exist outside of someone else or something else.”

The problem with this, and much of the discourse about Talley’s life altogether, is that it all revolves around anything other than Talley. The life and legacy Talley made is much more than Anna Wintour or Vogue or the many negative experiences he had, and it’s frustrating that even in death, Black men at the highest echelon of their realm still are not considered central to their self-written story.

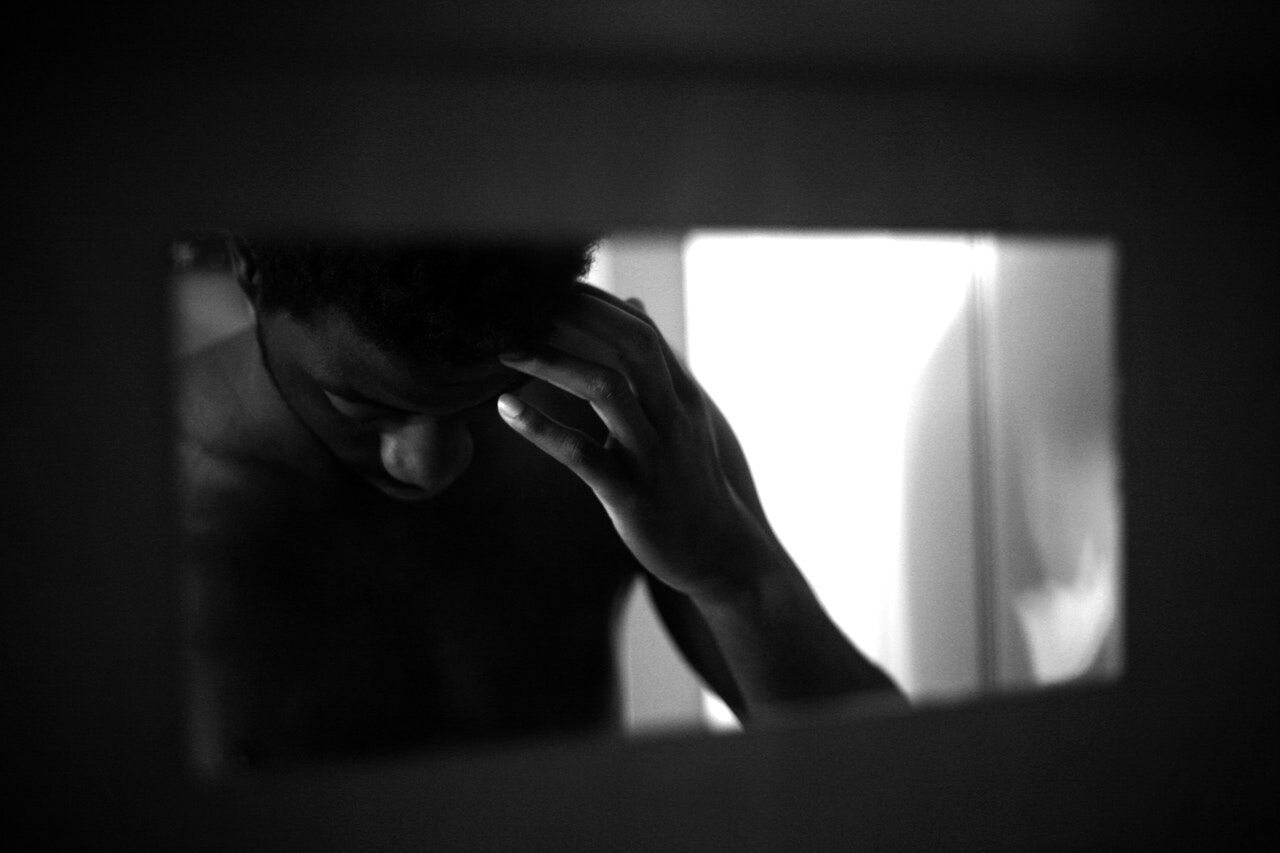

That’s not surprising to me. There are simply too many different examples to describe the way in how non-white people, especially Black people, are rarely allowed to be themselves, to be human, to exist outside of someone else or something else. Unfortunately, there is one recent example of that: the death of Ian Alexander, Jr., son of Regina King and Ian Alexander, reportedly by suicide.

Since the news was revealed this weekend — before King or others in their family could do so themselves — social media networks and media tabloids were bursting with post after post after post, drudging up Alexander Jr.’s life and career, his public comments and shared moments with his mother, and deep explorations into his social media or other interactions. This has become standard when any public figure dies, but it’s considerably more attention than his life received before then. Everyone being inundated with triggering content giving deep detail about a young person committing suicide, being forced upon us by merciless algorithms is already torture enough — I received several messages from people who had to relive their past suicidal ideation — but imagine being King, or the people around her. Not only have they had to make public statements and plan memorial services, but they have to deal with five-minute compilation videos of Alexander Jr. talking about his love for his mother, tagged and appended to every account or profile she has online.

Suicide is a terrible thing, and there are ways to talk about it, but the content farm taking advantage of that — and distracting us from actually making progress in understanding mental health and recognizing how hard and stressful these times are — is not acceptable. Even beyond that, it goes to the point that even in death, Alexander Jr. was more than those he loved or was related to. He was a DJ, a music artist, and a young man exploring his life, but articles rather talk about quotes King made about him in public appearances, screenshots of several tweets he made to come to terms with what was going on in his mind, assuming what he was dealing with or what were his “reasons.”

“We are not loved here. We are not seen as human here. We are being deprived of our humanity and our love.”

An article written by former INTO editor-in-chief Zach Stafford for Teen Vogue bought me back to Talley: he wrote, “Don’t get me wrong: A.L.T. was loved and he also loved himself. This warning doesn’t diminish the love that was his life. Rather, it is one that tells us we can, and we should, have even more love than he felt. But capitalism, the patriarchy, and even fashion are systems that can’t and will never love us back.”

While both Talley and Alexander Jr. lived different lives that came to an end differently, they both experienced what me, and so many of my friends, and nearly every other Black man in the entertainment or media industries, is coming to terms with: We are not loved here. We are not seen as human here. We are being deprived of our humanity and our love. We’re appreciated when we provide something, like our culture, and our knowledge, and our personality; but we’re often not paid well for it, not given gratitude for it, still disrespected and disregarded even if we get a semblance of what we work twice as far.

It’s not just Black queer men’s reality, and it’s certainly not limited to media, but that doesn’t make it easier to exist experiencing this.

Despite that omnipresent reality, we still fight to do this work, because we want to — for some of us, because they need to — and we fight to keep the love that’s constantly being deprived from us in a largely loveless society. And others are going to fight on too in similar realms. But remembering Talley and Alexander Jr., and the joy and positivity they shared at times despite all of this, I just have to say this.

Media, you don’t love Black men, especially Black queer men. You don’t see us. You don’t value us. Stop acting surprised otherwise when we die or suffer or stumble in this anti-Black, anti-queer world we’re living in.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox