I own an Army officer uniform. It will probably never be worn.

Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly of the U.S. District Court for District of Columbia ordered the military to begin accepting transgender recruits after President Donald Trump attempted to ban trans troops from serving in a series of July 26 tweets. Kollar-Kotelly, a Clinton nominee, first blocked the enforcement of that policy in a November ruling and again shot down an appeal from the Justice Department on Dec. 11.

Although that decision was heralded as a victory for LGBTQ rights, the fight is not over. Many transgender applicants will still be barred from joining due to roadblocks that make it extremely difficult for many to enlist.

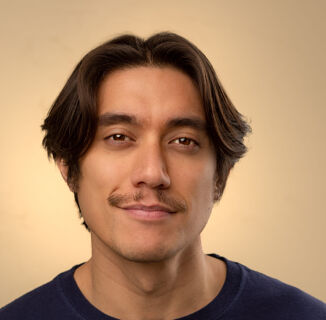

After graduating as West Point’s first-ever openly trans cadet, it’s unlikely I will serve a day in a job I have been training for most my life.

I spent six years preparing to enter the United States Military Academy (popularly known by its military post, “West Point”) and four years there studying to become an officer in the Air Defense Artillery. After a decade of expectation, I was ready to pin on my 2nd Lieutenant bars, swear an oath to the Constitution, and drive away from my alma mater as a newly minted officer of the United States. I had my orders ready: Ft. Sill for training, and then to Ft. Hood to join the 69th Air Defense Artillery Brigade.

At the time, I did not know that I would become a first openly trans anything.

The uniform may have been for a man, but after waiting a decade for the opportunity to join my brothers and sisters in the armed forces, I was determined to put my country before my womanhood. After coming out in December of 2016, I was immediately accepted by my superior officers and the majority of my peers. Professors, officers, and classmates had no trouble switching to my chosen name: Riley, a name I would legally change before graduation. I was treated solely based on my character and performance.

But in accordance with military policy, I was still restricted to male standardskeeping my hair short and wearing male clothing. But I knew I would commissionbecoming an officerand change all that.

Instead, just days before my graduation from West Point, I was brought into the superintendent’s office along with my entire chain of command (a captain, two colonels, and two generals), and handed a memo from the Department of the Army declaring me unsuitable for commissioning. Upon graduation, I was given a discharge and sent away.

Before I left, the superintendent would tell me, “You’re still our lady.”

I was one of the first direct victims of the administration’s desire to remove transgender service members from the military. On July 26, President Trump announced in a series of tweets that transgender personnel would not be allowed to serve in the military “in any capacity.” Military leaders were not informed of the president’s proposed policy, which Trump claimed the armed forces “cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption” that allowing trans people to serve openly would entail.

By August, he followed up his tweets by sending a memo to the Pentagon ordering them to begin plans to remove currently serving members.

The expectation of this policy change had existed since at least May, when I was discharged. The policy for active duty transgender service members was meant to include service academy cadets. This expectation changed under the new administration. I had the support of my entire chain of command, the medical staff, and my commissioning waiver was written and signed by a 3-star general. The military wanted me; the administration did not.

I am one of many. Countless other transgender military personnel have been forced to sit on their hands while their commissioning packets collect dust. Thousands more are waiting outside recruiters’ offices for their chance to swear an oath and protect the country they love.

President Trump’s attempt to ban open transgender service had immediate and tangible consequences. Service members have been denied medically necessary care, promotions, and deployments simply becauseuntil this weektheir commanders didn’t know if they would still be in uniform another year from now. This has had an extremely demoralizing effect on trans service members, their allies, and their units.

In response, several organizations and brave active duty service members took the government to court, and on Nov. 21st, they won.

The true win of these court cases was when the military publicly stated that it will comply with the court’s decision. On Jan. 1, transgender Americans armed with a doctor’s note can proudly express intent to enlist and begin the process of joining the nation’s largest employer of trans people. For those already serving, this means momentum on their commissioning waivers, paperwork, and most importantly, their medical care. For trans cadets in ROTC programs and service academies, this is a beacon of hope, as well the light at the end of the closet.

But the requirements to join are still stringent. A medical professional’s note that they are “stable in their preferred gender for 18 months” is required. Major roadblocks are behind this that make it difficult for a transgender person to achieve, and for many people, enlisting in the military may be an unfortunate catch-22.

There are many reasons that surveys have shown transgender individuals are twice as likely to serve in the armed forces. Many people, whether trans or cisgender, join the military to get away from their past, to pay for college, or simply because they cannot afford civilian life. For trans troops, the military can be a way of escaping pervasive discrimination in their local communities. Nineteen percent of trans people report having been homeless and 26 percent have been fired because they are transgender.

Joining also means validation of character: that what you bring to the team matters more than any differences in ethnicity, religion, orientation, or gender. It also represents how people like yourself can share in civic responsibility with others, showing that trans people are not a burden on society. We are part of it.

But let’s say you’re a transgender woman who wants to join the military to have the ability to transition. Because you’re disproportionately likely to live under the poverty line, you can’t afford to take hormones to meet the military’s entrance requirement. Because 28 percent of trans people report being discriminated against by medical professionalsor even turned awayyou may not be able to access a doctor’s office that will sign off on a note for you. Even if you can find an affirming provider, it’s possible you won’t be able to pay for the visits.

To have the chance to transition, you have to join the military. But to join the military, you have to transition.

At seven months on hormones, I am still new to the transition process, although most of the physical and emotional changes have already occurred. My only obstacle is the 18-month requirement. While this requirementas all medical requirementsis waivable, the immense support on my first waiver was not enough. I have no reason to believe that it would be accepted now. I might still try, but after nearly a year of watching and waiting, I’ve been exhausted by the delays.

A doctor’s note also implies that I must be seen by the same medical professional for 18 months for them to certify my treatment, which extends my wait even further. Countless others face the same predicament as I do.

Additionally, there are physical standards to meet. For transgender men, running or push-ups may be a hurdle. For trans women, the height and weight standards can be tough to meet without practice and a good diet. Flexibility in physical programs may be required. However, this is the same as any recruit, and active duty trans service members have proven that physicality is not an issue if disciplined.

The military, just as it did when transgender people were banned from serving, is forcing trans people to deceive their recruiters and superiors just to be able to serve. Had I lied while I was a cadet, I would be an officer right now. At graduation, the only barrier between me and becoming an active duty lieutenant was a diagnosis of gender dysphoria; I had not undergone any treatment and simply declaring myself as transgender were not reasons to be discharged. I am the same as I was then: fully trained and capable of leading a team of soldiers, yet I am still not allowed to become an officer.

However, this is bigger than my story. The court’s decision is not about me. It is about all of us, transgender people and their allies alike. It tells the world that someone tried to break us, and we held firm; we fought back. Their hammer met our anvil. There is more work to be done, but we have this victory. My story is not done; our story is not done. We are here, we are acknowledged, and we are ready to fight.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Impact

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox