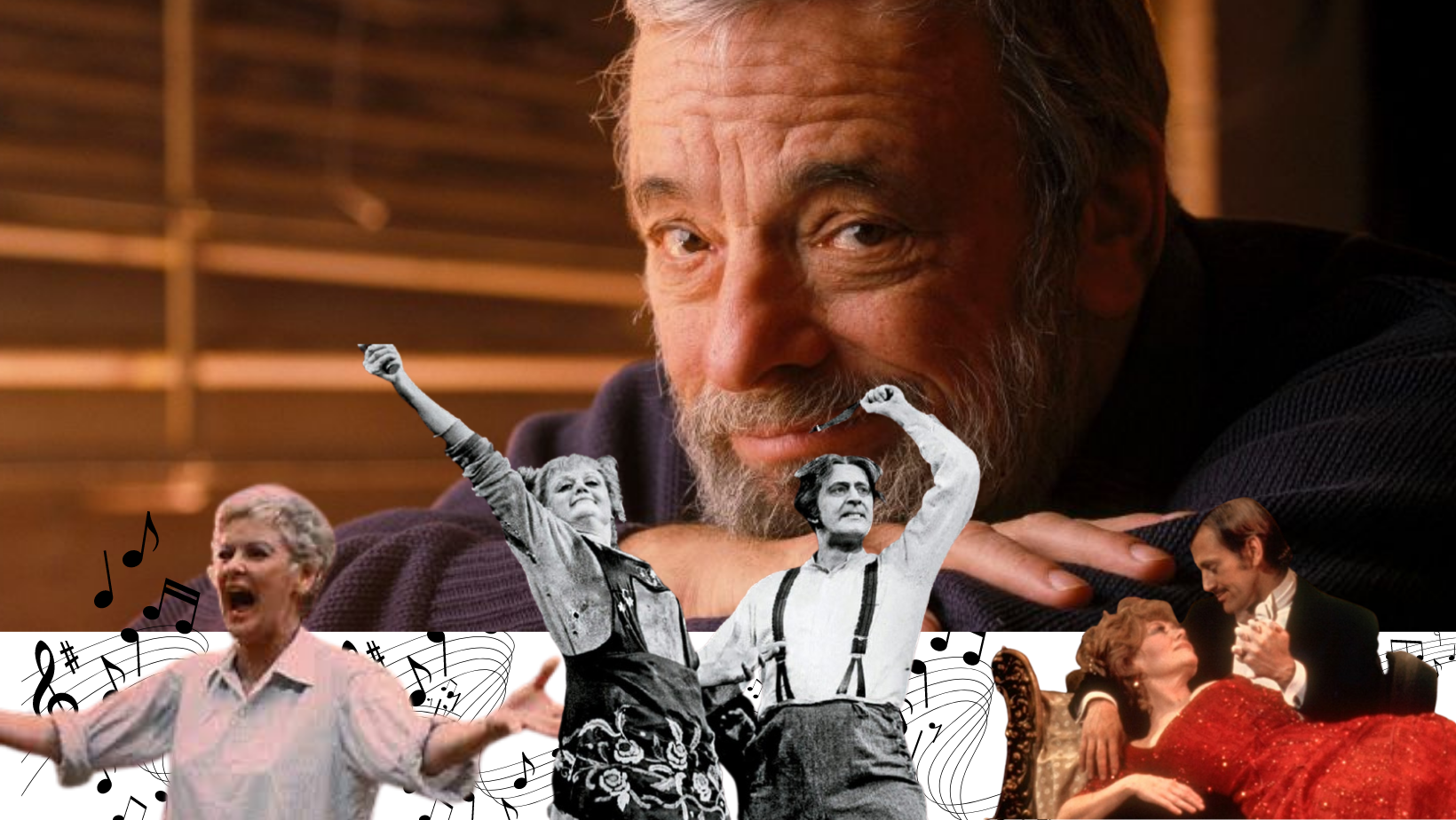

There are some artists who are so entrenched in your consciousness that you can’t remember a moment when you didn’t love them with everything in you. My earliest memories are of riding in the backseat of the family car with a tape of the original cast recording of “Follies” playing. Before I knew what gay people were, before I knew what love was, before I knew who I was, I understood the women Sondheim wrote about: the ones who bragged that they’d already “buried [their] rage” with a boy half their husbands’ age in the grass (bet your ass.) I understood, on some level, the duality of Sondheim’s women, his men, his people. When he describes, in “Who’s That Woman,” someone who is “joking, but choking back tears,” I got it. He was talking about me, but I didn’t know it yet.

While Sondheim lived, he wasn’t thrilled, it seems, with his reputation as an important gay artist. As he said to activist and “The Normal Heart” playwright Larry Kramer, “everything with you is gay, gay, gay!” It wasn’t meant as a compliment. He only wrote one score, to my knowledge, that features a gay relationship (2003’s “Bounce.”) But to me, every last one of his plays is, while not explicitly featuring gay people, about us. About the way queer people talk and act and think and relate to each other. The way we read each other for filth, tease each other, indulge in our worst instincts together. The way we create and nurture friendships. The way we understand reality. And our honesty: the brutal honesty that made so many of his works so cuttingly ingenious. How else does a musical like “A Little Night Music” work, with its dizzying, myriad perspectives? How else does one person access the internally of a courtesan at the end of her life as easily as he accesses the perspective of her granddaughter, whose life is just beginning? It was a knowledge of humanity that he had: specifically the knowledge of how queer people feel things. How we use humor to hide the way we’re hurting, and how at times we’d rather die than say the raw, vulnerable truth of how we feel.

I didn’t understand love or relationships at age 7, but I understood what it meant when Buddy in “Follies” sang, “I’ve got those god-why-don’t-you-love-me-oh-you-do-I’ll-see-you-later blues,” recounting his unfulfilling yet perfunctory extramarital affair with Margie, a girl who is crazy about him and who, for that very reason, holds no appeal for Buddy. Sondheim knew the way we think: the inherent emotional masochism present in even our healthiest relationships. He understood love at every stage: the beginning, the interminable middle, in which couples like those on display in “Company” squabble and bitch and moan and sometimes break apart. And the end. He knew very well about the ending. Whether it’s the abusive Sweeney Todd chucking Mrs. Lovett into the over at the end or Desiree Armfeldt’s beautiful, remorseful ballad of a love lost to bad timing, “Send in the Clowns,” Sondheim’s characters understood the violence, pain, and discomfort bourne of intimacy. They also knew that no matter how it ends, love is always worth it.

What’s more, he believed in love as an important subject of the American theater. He knew that, where the theater is concerned, there can be no grander theme. For Bobby in “Company,” being in love was worth being annoyed, invaded, accompanied, and paid attention to. For Sally in “Follies,” love was worth going insane for. And for Desiree, for Sweeney, for Mrs. Lovett, for Mary Flynn, Dot, Toby, Heinrich, Charlotte, Charley, Tony, and Maria, love was hell and salvation, agony and ecstacy, capable of being sung in both a major and a minor chord.

But more than anything else, he gave us a way to see ourselves—the way we love—in stories that had, for so long, been the exclusive province of straight playwrights. He told queer stories under cover of nostalgia, of pastiche. He perverted and beautified the Great American Songbook. But out of everything he gave us, the thing I’m most grateful for are the characters. People that I’ll never, as long as I live, stop thinking about. I’ll never stop trying to get to the bottom of what they think and feel, I’ll never be sick of hearing them harmonize. I’ll never tire of the brilliant, acerbic, razor-sharp observations they make about life, art, love, drinking, remembering, and being.

“These are my friends,” sings Sweeney Todd when he’s at last reunited with his beloved razors. That’s how I feel about the people, the lives, the internalities Sondheim gave me a glimpse into. He continues to do this, because as every Sondheim lover knows, the songs only get deeper with each listen, with each passing year, with the influx of new people into one’s life and the loss of others. I pick up his music daily, and I drink from it deeply. “These are my friends,” I sing to myself. “See how they glisten.”♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox