The jazz musician Billy Tipton is something of a totem of transmasculinity, a figure of mythical proportion. Some of you know I’ve been writing (trying to write) a book inspired by him for years. He’s fascinating and incredible, and not for the reasons you think.

Tipton played regional jazz in the 1950s. He met Duke Ellington. He was mentored by the Teagarden family, consisting of the legendary jazz trombonist Jack and his lesbian sister, Norma. He was a trans guy whose safety and success depending on him living stealth and being “woodworked.” This was how most trans people survived in the past. They tried to pass and hoped nobody asked too many questions. They didn’t seek out community, because it was dangerous. Sometimes, community found them. More often, it didn’t.

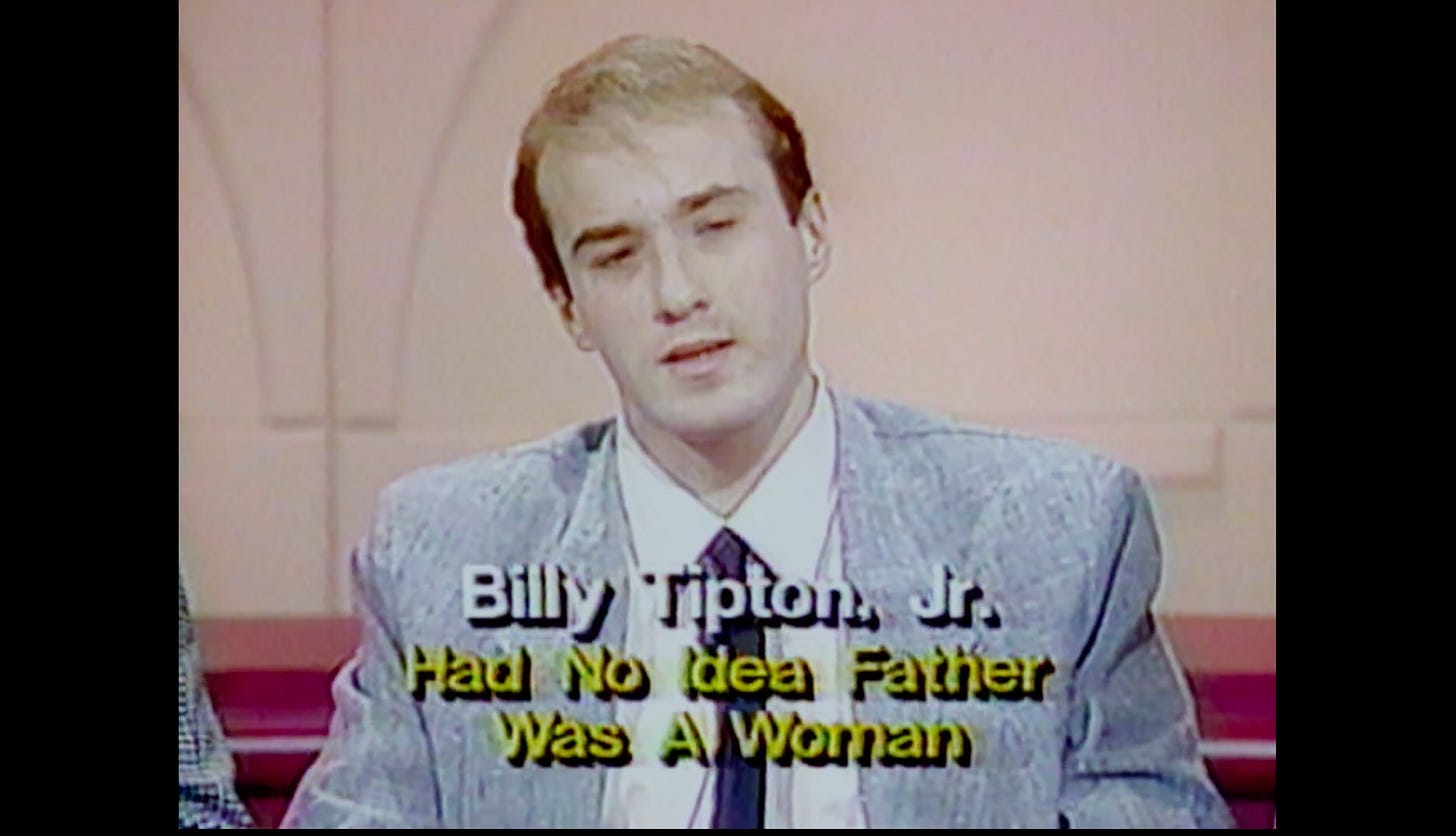

If you know about Tipton at all, it’s probably due to the way his 1989 death was treated as a tabloid story. Here’s what happened: Tipton, by the end of his life, had settled down with his wife Kitty Kelly and three adopted sons. One of those sons, Billy Jr., was with his father when he died. The story goes this way: Tipton dies in his son’s arms. The paramedics arrive and discover Tipton’s “female body.” The press goes wild. Suddenly, Tipton’s entire life was rewritten in the wake of his death. “Woman masqueraded as a man for decades.” “Even wife and sons didn’t know.” The trans deceiver trope attached itself to the story, thanks to lazy, transphobic reporters, and a biographer with her own ax to grind.

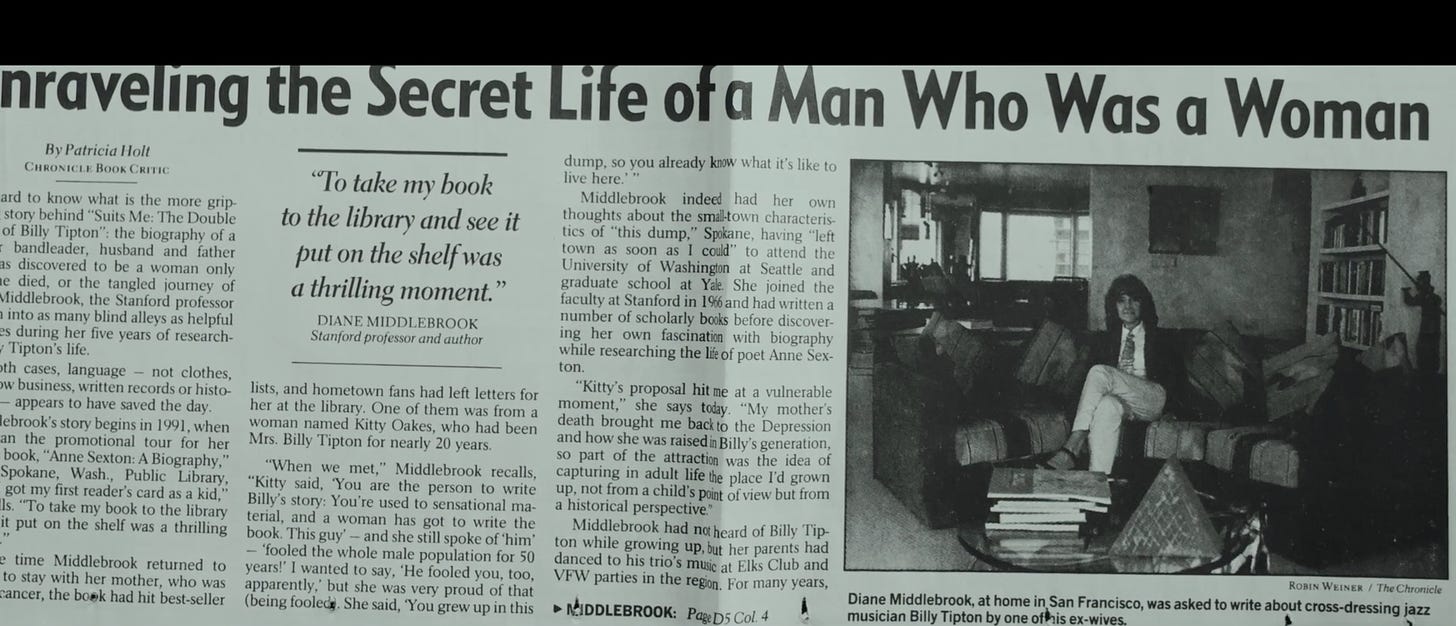

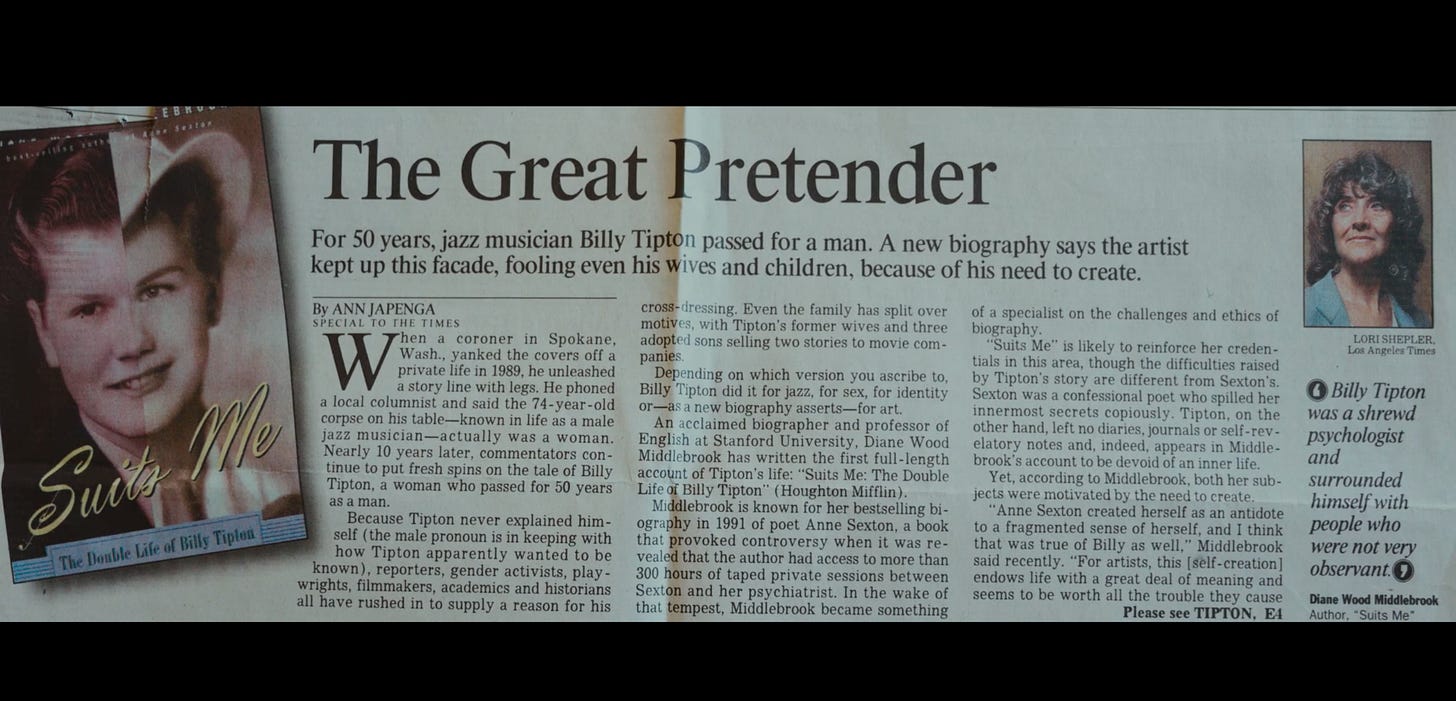

When Kitty Kelly reached out to biographer Diane Middlebrook about writing Tipton’s life story, Middlebrook took the assignment. Her 1998 Tipton biography, however, took the position that Tipton’s transness was somehow motivated by a feminist desire to thrive in the music scene. Middlebrook recast Tipton as an “ambitious woman” who wanted to get ahead in the world of 1950s jazz by dressing as a man. She wrote the book from Kitty’s imagined perspective, focusing on Tipton’s “deceptive” nature and leaning into the broader media interpretation of Tipton as a lier, a con artist, and a fraud.

This is what cis people did with us for a long time. They recast us as confidence men: great deceivers trying to pull the wool over everyone’s eyes rather than desperate people trying to survive. In many corners of the world, that’s how we’re still perceived.

Chase Joynt and Aisling Chin-Yee’s No Ordinary Man, which had its festival premiere last year and is in theaters now, is an attempt to settle the score. By reclaiming Tipton’s story from the tabloids, the documentary favors a strongly empathetic narrative, what Joynt refers to as a “poly-vocal” approach. The script, co-written by Chin-Yee and Amos Mac, jumps between interviews with trans historians like Stephan Pennington, C. Riley Snorton, and Susan Stryker, actors like Marquise Vilson and Scott Turner-Schofield, and archival footage to try and piece together all the missing parts of Tipton’s life history. Parts that were either ignored or willfully left out by Diane Middlebrook two decades ago.

No Ordinary Man also includes casting sequences for an unnamed Billy Tipton biopic. As a rotating cast of trans male actors, musicians, and speakers read for the role, viewers are keyed in to dramatized scenes from Tipton’s life.

Tipton’s son Billy Jr. also makes several poignant appearances, both in flashback and real time. At once point, the trans rights pioneer Jamison Green is shown meeting Billy Jr. and musing on his own relationship to the Tipton legend. In voiceover, Green tells the story of when he explained to his young daughter that he was going to transition. “I’m going to change,” he said. At first, his daughter was confused, but he told her that she’s going to change, too: She hasn’t gone through puberty yet. This worried her, too: how much will I change? But Green reassures her: “we will always recognize each other.”

All of it is deep, heartbreaking stuff, because so many of us have been waiting for a movie like this forever. But one of the most moving parts of the film involves its co-writer, Amos Mac, speaking to one of the actors auditioning for the part of Billy. For the scene, Mac is explaining about Buck Thomason, the transmasculine son of the owners of a radio station Billy worked for. “I’m fascinated by the character of Buck Thomason,” Mac says, explaining that as far as we know, Thomason was the only other trans man Tipton ever met or interacted with in his life. Questions abound: were they friends? Did they talk? Did they share what they knew with each other? Did they completely ignore it? Mac admits at one point, “I don’t think that Billy Tipton was thinking about gender the way we’re all thinking and talking about gender.” He was cut off from it, and his safety even depended on his not thinking about his own transness too deeply or for too long.

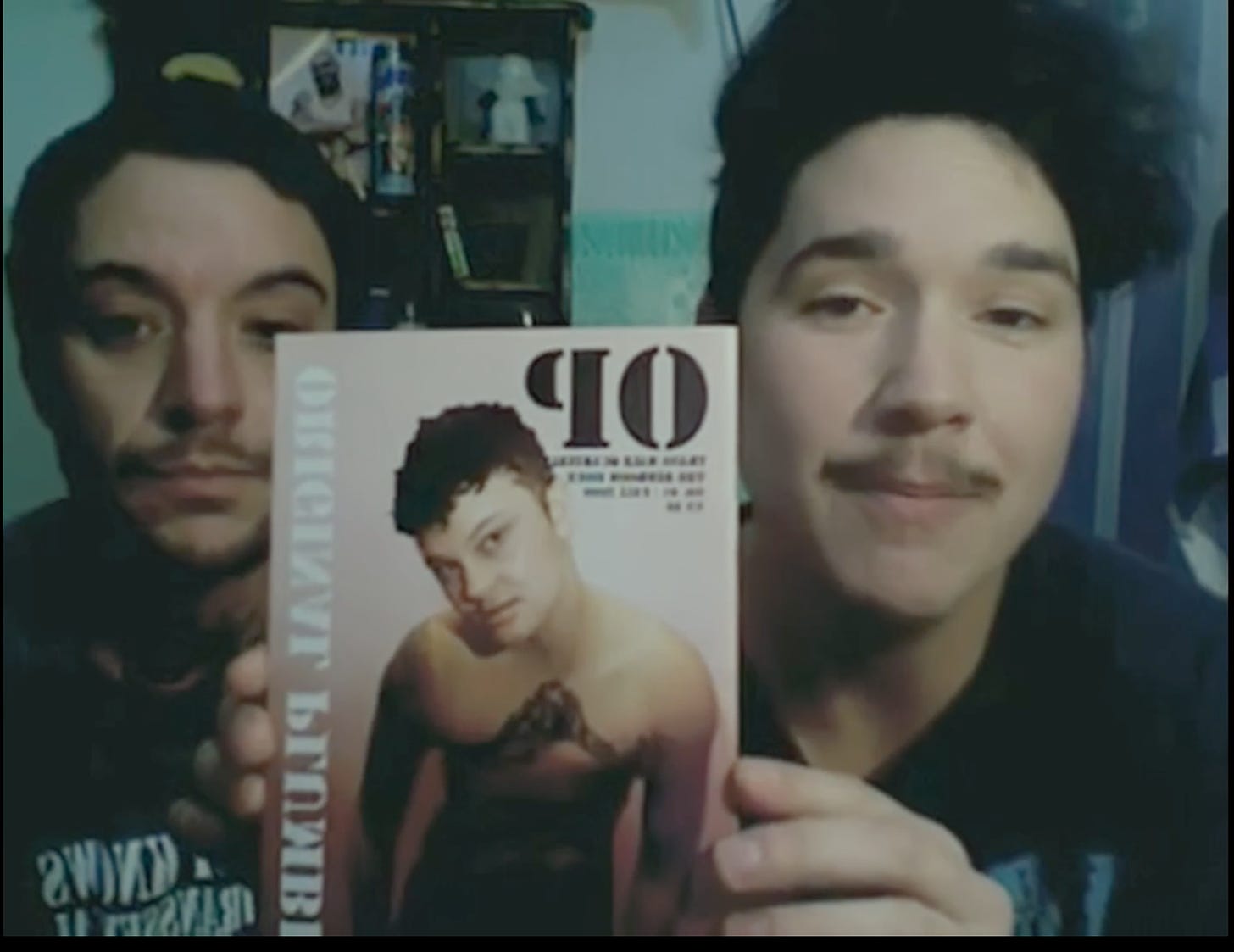

Later on, Mac tells the actor Alex Blue Davis, who is auditioning for the Tipton role for this scene—a fictionalized one in which Tipton and Buck meet for the first time—that it’s as if he’s seeing himself for the first time. Seeing that he’s possible, in the reflection of this other trans person before him. Blue Davis is taken aback, trying to remember what that moment was like for him the first time. He’s been out of the closet for so long, he says, and when he first came out he was so ashamed and wanted nothing to do with other trans people. But then he does remember. He looks at Mac, sitting offscreen. “Actually,” he says, “it was you.” He describes first seeing Mac in a video promo reel for Original Plumbing, the FTM zine created by Mac and Rocco Kayiatos in 2010.

I’ve known Amos and Original Plumbing since about 2009, and I count him, as well as OP co-founder Rocco Kayiatos, as a friend and a personal hero. Hearing one trans guy say it triggered my own memory of meeting Mac.

In 2011, I was working at my first media job. I’d known about Original Plumbing for a while: It was an adored, foundational text of transmasculinity, a playful, colorful celebration of trans art, bodies, and identities. It was also way ahead of its time. OP was a breath of fresh air in my world, where I was associating only with cis people, because I didn’t know where other trans people were, or even if I’d have anything in common with them. I wrote to Mac telling him about myself and asking if I could write for the magazine. He said yes, and we struck up a friendship. But that wasn’t the first time I actually met Amos.

During my senior year of college, I was miserable. I had been out as trans for about a year, and I fucking hated it. Like Alex Blue Davis, I wanted nothing to do with transness, because I was still ashamed of it. It felt like a personal shortcoming: I had failed to be cis. I hadn’t even summoned the courage to cut off my long hair yet. I was trying my best to deal with what I then thought of as the unacceptable fact of my transness. My entire life before that point, I’d assumed I could just sort of lie to people and want to die all the time and get through life that way. But things had gotten out of control and by the time I turned 19, and events had passed which made me realize that if I didn’t address the problem somehow, I would end up causing serious physical and mental harm to myself. And that wasn’t acceptable. So I came out, reluctantly. It sucked. I dragged myself to the Center in New York, where twice a week you could meet in a shitty windowless basement, listening to other trans guys—all of whom were on HRT and many of whom were passing—talk about surgeries and girlfriends and all the ways of being sad. It was relentlessly depressing. I felt like by coming out I had signed a contract that said “by doing this, you will promise to be fucking miserable forever.”

Despite all this, I somehow managed to take a class that year, the first of its kind being offered at NYU. It was called something along the lines of “Transgender History and Culture,” and I’m pretty sure I was the only trans person in it. The professor was cis, even though she was super cool, and everybody in the class seemed so easy and breezy about this shit, and there I was dying in the corner trying my best not to be seen. It just felt like being naked all the time.

But one day, we had a guest speaker. It was Amos. He looked amazing: he had a high pompadour and a great mustache and a bright, runaway laugh. I thought he was the most beautiful man ever, and I didn’t think guys like us could be beautiful like that. Amos wasn’t the first trans guy I’d ever seen, but he was the first happy trans guy I’d ever seen. And he was making art. He showed us this cool project he’d just started, a zine called Original Plumbing. The cover was so dreamy and beautiful: it showed a trans guy wearing an Ace bandage—the same kind I was struggling to breathe in at that time—and looking up at the camera with knowing eyes. He was a happy trans guy, too. Maybe they were everywhere.

The thing about trans guys is that even though we’re around, we’re not always easy to see. I’m sure I pass a few trans guys on the street every week, but I don’t know it, because I can’t tell. We pass, for the most part, and unless somebody looks visibly queer, you probably won’t be able to tell a trans guy from a cis one. There was something really beautiful about seeing a lot of trans guys in a room together in the documentary for that reason. It’s not something you always see in the world. Even in a big city, and even if you’re looking for it. The impression you get by the end is of a wide, expansive hidden history. People connected across time and space without even knowing it. A legacy that keeps being built and re-built. A patina forming on the face of that legacy from years of research and reclamation. “Hardly anyone is ever truly alone in this world,” someone says near the end. I don’t think a kinder, more optimistic phrase exists in the English language.♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox